Misdirection. A form of deception in which the attention of an audience is focused on one thing in order to distract its attention from another. Managing the audience’s attention is the aim of all theater, it is the foremost requirement of theatrical magic. – Wikipedia

On November 6, 2018, in a much-anticipated game on the first day of the NCAA men’s basketball season, the preseason 4th-ranked Duke Blue Devils, led by the incomparable South Carolina freshman Zion Williamson, thrashed the 2nd-ranked University of Kentucky Wildcats basketball team by a score of 118-84.

Despite breathless coverage of this match-up on ESPN, truly nothing was at stake. Duke and Kentucky are both too-big-to-fail sports programs, with too-big-to-fail coaches, that surf the crest of an endless wave of media attention.

Drama requires a moment of reckoning, a rising to the occasion, a reaching beyond oneself. But the Duke and Kentucky programs don’t rise to the occasion. They are the occasion, and so the facts of their existence are all that matters, not the meaning of their existence.

Players shuttle from UK and Duke programs to the NBA so rapidly one can barely remember their names. A few recent examples. Tyler Herro, Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, Kevin Knox, De’Aaron Fox, Malik Monk, Jamal Murray, R.J. Barrett, Cam Reddish, Marvin Bagley III, Wendell Carter Jr., Jayson Tatum.

These players barely imprint and are effaced the moment a heralded new recruiting class arrives on campus. But Coach Mike Krzyzewski and Coach John Calipari abide. They are the facts to which we must ascribe meaning.

Especially Coach Cal. Because if Coach K is the constant in college basketball against which all else is measured, Coach Cal is the sport’s variable, a bobbing, viscous image of the sport and its impact on American society in the 21st century.

One and Done

Press foliage has in recent years made much of Coach K’s conversion to the One-and-Done recruiting philosophy Coach Cal has famously used to market UK basketball to elite high school players. Coach K – with his 1,000 wins and Olympics coaching resume – is far more iconic than Coach Cal. As a result, the Coach K conversion storyline implicitly validates the One-and-Done approach and, perhaps for the first time, has allowed pundits to consider Coach Cal as a Coach K peer in the college basketball coaching pantheon.

In reality, comparisons between Coach K and Coach Cal are silly. Track the coaching records of Coach K and Coach Cal from 2000-2019, a span of 20 years. Draw a line between the 2004-2005 and 2005-2006 seasons, when the NBA prohibited players younger than 19 from going pro and effectively locked One-and-Done into the league’s collective bargaining agreement and into the DNA of college basketball recruiting.

No gap separates Coach K’s seasonal tally of wins and losses prior to and after the inception of One-and-Done. In the five seasons between 2000-2001 and 2004-2005, Coach K averaged 30 wins and 5 losses a season. In the ten seasons between 2005-2006 and 2014-2015, when college coaches could openly recruit players interested in vaulting to the NBA after one season, Coach K averaged 30 wins and 6 losses a season. In other words, he was equally successful with and without One-and-Done, his teams on average winning 5 of every 6 games.

Coach Cal became a far more successful coach after One-and-Done became part of the recruiting landscape. Indeed, Coach Cal assumed head coaching duties at the University of Memphis prior to the 2000-2001 season. He hopped to the coaching position at Kentucky prior to the 2009-2010 season. As the Memphis coach, between 2000-2001 and 2004-2005, Calipari averaged 23 wins and 11 losses a season. Clearly Coach Cal is under any circumstances a gifted coach. But 23/11 are not Coach K numbers. They are not Naismith Hall of Fame numbers.

However, between the 2005-2006 and 2018-19 seasons, Coach Cal’s teams have averaged 32 wins and 6 losses a season, an average increase of 9 wins and decrease of 5 losses from his first five seasons at Memphis. Coach Cal was a good coach between 2000 and 2005, whose teams on average won 2 of every 3 games. After 2005, Calipari suddenly became a great coach – a Naismith Hall of Fame coach – whose teams on average won 5 of every 6 games!

So these are the facts. What is their meaning? Why do they matter?

These facts matter for two reasons. Coach Cal has parlayed his skilled efforts to recruit and win games with players whose primary goal is to leave college as soon as possible for the NBA into an unseemly level of wealth and influence at the University of Kentucky, a state-funded institution. Since 2009, when Coach Cal jumped the border from Tennessee to Kentucky, the net value of his employment contracts has exceeded $100 million (with 6 extensions negotiated in this timeframe, in what now amounts to a lifetime employment contract). In this period, of course, higher education funding in Kentucky has withered and tuition at state universities has soared. John Calipari is one of the three highest-paid public employees in the United States (the two others are college football coaches Nick Saban and Dabo Swinney)!

In addition to enriching himself while at Kentucky, Calipari also has burnished his reputation as a caretaker father figure for his players, most of whom are African-Americans. For this reason, Coach Cal gets a pass on the financial shenanigans because his teams win games and he personally cares for his players.

But he shouldn’t get a pass. Calipari has profited enormously from the halo surrounding his relationships with young players. His benign image masks and deflects attention from the relationship between youth basketball’s sordid underbelly and the complex and evolving (but still-all-too-often-desperate) circumstances of African-American males in the United States.

Border State Myths

Kentucky fought with the Union during the Civil War. With a relatively small African-American population and minimal economic dependence on the cash crops that supported the institutions of slavery, the state has benefited from the perception that it is not really part of the South, and that no matter what racial issues the state faces, they pale in comparison with the legacies of slavery and racism in the Deep South.

The perspective on Kentucky is both fair and misleading. Clearly Kentucky’s most pressing economic and social problems have long centered on the economic poverty, social pathologies, and environmental destruction visited upon regions in the state most dependent on coal mining and subject to its anaconda squeeze. Most of the people in these regions are white and their circumstances are about as dire as one can find for any population living anywhere in the United States (Knox County, the poorest in Kentucky, is 98 percent white). In this sense, Kentucky’s pain has little to do with either Coach Calipari or the American South as a racial state of mind.

Calipari himself was raised in Pennsylvania rose to coaching prominence in Massachusetts, and remains (perhaps reassuringly for those seeking to demarcate the distance traveled from the overtly racist Rupp era) a cosmopolitan presence within a starkly provincial region. Coach Cal’s smooth criminal capacity to ingratiate himself with just about anyone (so long as they don’t claim his attention for more than five minutes) may strike some as Mephistophelean. But as the song goes, Coach Cal’s made no effort / to put down KY roots. / He travels the nation / in search of recruits. So yes, it’s hardly fair to ask Coach Cal to sacrifice his wealth or in any way use his influence to help the state of Kentucky and its students; that’s never been part of the grand bargain.

On the other hand, Calipari has benefited personally from profound and steep racial inequities on which his own celebrity and wealth surfs. Coach Cal may owe nothing to Kentucky and to the students who attend its public universities (including any effort to actively recruit within the state). Nonetheless, his Border State positioning since 2000 (first at Memphis and then Kentucky) has strategically allowed him to establish a national recruiting brand pretty much everywhere outside of Kentucky.

Race Matters

In the past 60 years, African-American males have artistically reimagined the game of basketball and claimed for themselves its culture. Most elite collegiate basketball players in the United States are now African-American (in the ESPN 100 list of top high school recruits in 2018, the 1st non-black player on the list was Tyler Herro, ranked at #30). For African-American males, basketball remains an urgently, mystically coveted way out of poverty, and the most illuminated and cosseted path to prosperity and acceptance within the American mainstream.

But the sport should not be asked to bear this burden! So few black collegiate athletes – fewer than one percent – achieve meaningful or enduring professional athletic success. And yet from an almost pedophilically young age, sports media (ESPN in particular) and national player development and recruiting parasites attach themselves to these young athletes. The effect is to create a reality distortion field that virtually deconsecrates any other legitimate professional identity for young black males. We have become used to assuming that most basketball players will be black but fail to appreciate the degree to which that assumption is the mirror image of the assumption that most doctors or attorneys or scientists or engineers will not be black.

African-Americans may have achieved massive overrepresentation in “fake” professions such as basketball and football (76 percent of NBA players are African-American and 66 percent of NFL players are African-American). However, fewer than 1,500 black athletes play for teams in the NBA and NFL. Unrelenting media focus on these “success stories” casts into shadow the hundreds of thousands of young black males who bet their future on these sports without fully appreciating that their odds for achieving enduring success as professional athletes are vanishingly small. Because Coach Calipari’s celebrity-redeemer image and saccharine sound bites sanctify this black athlete puppy mill, he contributes, perhaps more than any other single individual, to the air-brushing of a massively profitable sports-entertainment ecosystem which mostly consumes African-American male athletes as raw material.

On the other hand, blacks remain truly underrepresented in “real” professions within business, engineering, science, medicine, and law that employ more than 10 million Americans. Within these stable, well-paid, lifelong employment fields, blacks, who represent 11.7 percent of the working age population, fill less than 7 percent of the positions (these employment disparities are even more striking for Latinos). By contrast, Asian-Americans, who represent 5.8 percent of the working age population, fill more than 13 percent of these positions. Any racial proportionality in the distribution of these high-paid, high-status, high-influence professions would over time add hundreds of billions of dollars in wealth and income to African-American families, while also creating a different, and far more sustainable opportunity horizon for young African-American males.

So here’s the problem. Calipari’s personal fortunes are emblematic of the vast wealth hundreds of thousands of young African-American athletes create for largely white institutions and for white leaders at the apex of these institutions, from AAU programs to sports apparel and footwear companies to sports media empires to collegiate athletic empires to professional sports teams and leagues. A tiny percentage of African-American athletes receive any significant portion of this wealth, while the remainder remain losers in what is essentially a rigged lottery.

In the past ten years, nothing has contributed more to this chasm between athlete expectations and reality in collegiate sports than the NBA’s One-and-Done rule. And no coach has more disingenuously capitalized on this rule than John Calipari, personally benefiting from this chasm while adeptly serving as the agent of misdirection for the sport and its business partners.

Coach Cash

During the 2008-2009 basketball season, John Calipari was already one of the highest-paid coaches in college sports, earning $2.35 million at the University of Memphis. For the 2018-2019 season at the University of Kentucky, Calipari’s earnings exceeded $9 million, making him among the top 3 or 4 most highly paid coaches in all of college sports. In this span of 11 years, Calipari’s compensation – already very high – has nearly quadrupled. In this period, state funding for the University of Kentucky has declined precipitously. The state currently funds only 6 percent of the University’s annual budget (in 2008, the state funded 16 percent of the University’s budget). At the same time, base tuition at the University of Kentucky for state residents has soared from $7,848 annually to $12,245, an increase of nearly 60 percent.

Put another way, in 2008, Calipari’s earnings represented about 1/140th of public funding for UK. In 2018-19, Calipari’s earnings represent 1/30th of the public funding for the entire university. Calipari’s 2018-2019 earnings would fund the salaries of 80 professors at the University of Kentucky. His earnings would pay annual in-state tuition for 700 students!

Money that flows through major college sports programs has more than a bit of the feel of a laundering operation. There is little transparency, even at publicly funded universities, and significant off-balance sheet accounting that makes it difficult to parse from where and whom money arrives and to whom it is disbursed. Schools like the Universities of Kentucky and Alabama emphasize that their athletic budgets are entirely separate from the school’s educational budgets, as if this somehow absolves the athletic programs and the schools themselves from responsibility for the core mission of the school. However, the schools cannot escape the logic of athletic department claims to autonomy.

On the one hand, such separation probably makes sense, as it simply confirms more openly that college sports are a business. If so, the schools should absolutely pay their athletes, who are essentially employees of the college in a business venture that benefits the school financially. On the other hand, why should athletic programs operate separate budgets? Why should these operations not reflect and fold within the larger educational mission of publicly funded schools? At what point, does the autonomy and influence of major public college athletic programs become a case of the tail wagging the dog?

Whether Calipari, specifically, is worth the King’s Ransom he demands to bless the University of Kentucky basketball program remains an open question of course. It doesn’t take advanced analytics to realize he provides nowhere near the value to UK that a far less expensive coach such as Mark Few offers to a mid-major program like Gonzaga (at the poverty line salary of only $1.8 million). Unless one realizes that Calipari earns his cash, not because he is exponentially better at coaching than Mark Few, but because he is exponentially better at burnishing the immensely more valuable business brand of the University of Kentucky and of college basketball.

Servant Leadership

In 2014, Coach Cal published a book called Players First: Coaching from the Inside Out, which enunciates his faith-driven philosophy of servant leadership. In Players First, Calipari tells us that his players mean everything to him – more than the NCAA, more than the Big Blue Nation, more than any personal ambitions he harbors for himself. His players, past and present, are his sons.

Okay. Fine. Whatever. We get it. Unlike other basketball coaches, Calipari loves his players. But focusing on Calipari’s personal relationship with his players misses the point, which is that in every other conceivable way not involving these personal feelings for his players, Calipari is the insincere, bland, insipid face of a dark and disturbing marriage between sports and business, which extracts enormous financial value from young black athletes and then discards them like so many blown mountaintops in Kentucky coal country.

It’s a common trope that Calipari gradually disfavors his own players as they move beyond being adorable freshman and become more the plodding sort of four-year player who will never be good enough to go pro. Indeed, on his legendary Twitter feed Coach Cal pretty much only mentions his One-and-Done pride and joys who have succeeded at a high level in the NBA. John Wall. Anthony Davis. Karl-Anthony Towns. Boogie Cousins, Willie Cauley-Stein. He doesn’t tweet about his players who never make it to the NBA, or who are barely hanging on in the NBA or, heaven forbid, in the G League or overseas.

Coach Cal is a social media prodigy. His Twitter account claims 1.6 million followers, more than pretty much every other college basketball coach combined. The magnitude of his online following speaks to his cultural sway, specifically in the African-American community, where he may well be the most recognized, admired, and influential white face in college sports.

One might assume Calipari’s influence implies a burden of responsibility to the sporting and African-American community that extends beyond Hallmark exhortations. But Cal is only a basketball coach, not a social activist and not a philosopher. His Twitter message is integral to his coaching mission, and his coaching mission is recruiting the best high school basketball players in the nation – keep the turnstiles moving. Twitter is therefore the perfect forum for Coach Cal because it provides the ideal environment for invoking good feelings and positive emotional responses, for connecting without communicating.

And so perhaps Coach Cal’s feelings are the point after all, because they are the source of his value as an agent of misdirection. Calipari is a highly skilled motivational speaker who reinforces our instinct to judge people on the basis of their words, not their actions. He plays our weakness for personal narratives and character sketches and virtuous homilies. We lose ourselves in his celebrity moments (Drake!). We should not be surprised, then, that on his Twitter account (and on his website, and everywhere else, actually), Coach Cal has literally nothing to say about the pressing circumstances and challenges of life for young black males in the United States. Nothing. Ever self-referential (and reverential) Calipari’s I can’t breathe moment occurred 2012 when he was standing next to POTUS.

Two and Through

John Calipari insists he does not love the One-and-Done rule, and more than once has voiced his support for the Two-and-Through rule proposed by NBA Commissioner Adam Silver, requiring players to stay in college for two years. But Calipari’s been clear he would not support a return to any option for high school students to jump directly to the NBA without going to college. And while many folks writing on this topic have properly pointed out that age or college requirements for mostly black basketball players smack of paternalism, the larger point is that colleges and coaches benefit far more from One-and-Done or Two-and-Through than players who might otherwise jump directly to the professional ranks from high school.

What would college basketball look like with no One-and-Done or Two-and-Through rule? It might not look any different than it does now, particularly as many top collegiate players would probably opt to leave school early for the NBA draft anyway. But recruiting could definitely change. And this is where the rotten foundations of college basketball truly rest. Not on the path from college to the NBA. But on the path from high school to college.

High school athlete recruiting – with its sinister sneaker overlords, AAU Svengalis and putrid player rankings – claims the attention and cements the priorities of African-American boys and their (often-poor, single-mother) families before they hit double digits. Minority athletes aren’t encouraged to view college as an educational end in itself, or as a destination on the path to a long-term professional identity. College instead appears before them as a pearly gate, the last stop before they enter professional sports heaven.

We shouldn’t forget that John Calipari wrote the One-and-Done playbook at Memphis, on behalf of Derrick Rose and Tyreke Evans, two preternaturally gifted teenage athletes delivered to Coach Cal by legendary facilitator and connector William Wesley. Worldwide Wes remains a shadowy figure, perhaps at this point equal parts Marvel myth and mortal human, powerful because he embodies the mystery and aura of the destination. The Big Show! The NBA!

We can be sure Worldwide Wes really wants to get his kids into college because that is the only path to the NBA. There is no upside for him, or for them, if they stay more than a year. If they aren’t good enough to go pro after one college season, they are probably not good enough to ever become elite NBA players. But the Wesley’s of the world are merely functional gatekeepers for a collegiate coaching cohort desperate for access to the kids who fuel the sports money machine. The coaches are truly the ass end of the food chain. The stank would fell a bear.

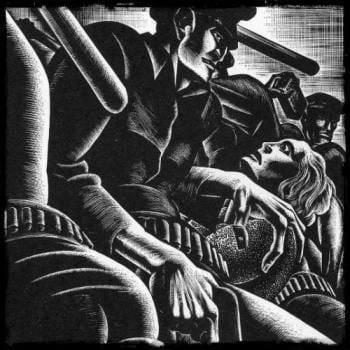

To be clear, on the grand scales of justice, Coach Cal is not the evil root. He is simply the sweet-smelling (near-rotten-smelling) flower nourished by the evil root. But the evolutionary value of the flower – what allows it to survive – is that it entices and seduces, freeing the evil root to do its dirty work in the background. It is precisely in this sense that John Calipari’s theatrics misdirect our gaze from the injustices and harmful effects of One-and Done recruiting in black America.

John Calipari is not a servant leader. He is a leader with servants, the black players who feather his nest, without whom he would be just another small-time basketball coach. Until we fully and publicly characterize that relationship, college basketball cannot properly serve the needs of the African-American community responsible for creating the magic and the blessings of the sport.