Background:

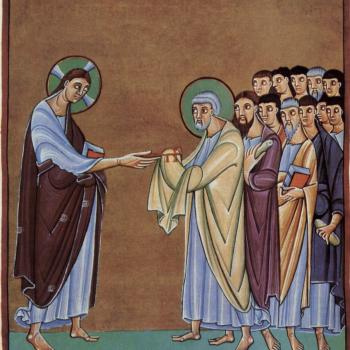

According to tradition, the Apostle Peter eventually came to the imperial capital, labored there for a time, and was ultimately martyred there by the Roman authorities. From a strictly historical perspective, Peter’s martyrdom at Rome is so well attested to in the ancient literary sources that the Lutheran theologian Oscar Cullman concluded that, “were we to demand for all facts of ancient history a greater degree of probability, we should have to strike from our history books a large proportion of their contents”.[1] The question that the present article hope to address is whether or not this belief is reflected in the Ascension of Isaiah. According Cullmann, it is a source that has not historically received the attention that it merits.[2]

The Ascension of Isaiah

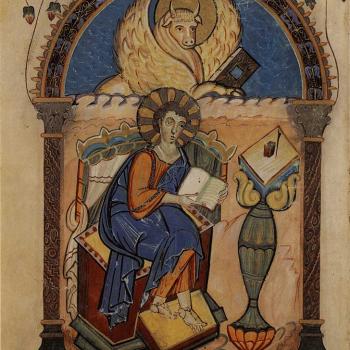

As per the Encyclopedia Britannica, the Ascension of Isaiah is a pseudepigraphal compilation of three separate works, the final form of which came from the hands of a Christian editor in the second century A.D. The first, the Martyrdom of Isaiah, is a Jewish work produced in the early first century. The second, Testament of Hezekiah, is a Christian work dated towards to the end of the first century, and the third, the Ascension of Isaiah, is another Christian work belonging to the early second century.[3] It is the third work in the compilation which potentially sheds light on the question of St. Peter’s martyrdom. The text in question reads as follows:

“2. After it is consummated, Beliar the great ruler, the king of this world, will descend, who hath ruled it since it came into being; yea, he will descend from his firmament in the likeness of a man, a lawless king, the slayer of his mother: who himself (even) this king 3. Will persecute the plant which the Twelve Apostles of the Beloved have planted. Of the Twelve one will be delivered into his hands.”[4]

Interpretation of the Text

Commentators are agreed that “Beliar” (Belial) is a reference to the Roman Emperor Nero in the above passage. As the Anglican scholar Robert Charles notes, “soon after the death of Nero the myth became current that (a) Nero had not really died, but was still living; and (b) that he would soon return from the East to take vengeance on Rome”.[5] This conviction developed into the notion of Nero redivivus, that is, the belief that Satan would bring Nero back to life.[6] It seems that the latter is meant by the author (especially given the date), and Daniel O’Connor suggests “that there is evidence here of a flowing together of two ideas and a compromise. On the one hand, Nero is seen as Antichrist, and on the other, the Devil appears to be the Antichrist”.[7]

Given that Nero is signified by the name “Beliar”, what of the “plant”, and who is the one of the Twelve delivered into the hands of Nero?

O’Connor lays out the interpretation of the entire text succinctly:

“If the passage is read without prejudice, the most convincing interpretation is that ‘Beliar’ is a cryptic name for Nero; ‘the plant’ stands for the Church; and Peter is the one of ‘the Twelve’ who is ‘delivered into his hands’…. The reason why Peter is not named may be explained from the standpoint of style. As in many passages pertaining to predictions of the future, this detail is omitted, that is, Acts 15:25, 26 and more clearly in Mark 14:18 (Matt. 26:21): ‘Truly, I say to you, one of you will betray me, one who is eating with me’”.[8]

Cullmann goes further than viewing the text merely as a possible reference to the martyrdom of Peter,[9] stating that it is “very probable”. “Paul, however, cannot be meant here,” he continues, “for according to ch. 3:17 the author uses the phrase ‘the Twelve’ in the narrowest sense. In that case this passage probably refers to Peter”.[10] Finally, Charles has no hesitations: “This work…is the first and oldest document that testifies to the martyrdom of St. Peter at Rome”.[11] While I would note that there is earlier literary evidence, — especially 1 Clement (ca. A.D. 96) — [12] it is hard to disagree that this passage in the Ascension is a reference to the martyrdom of the Prince of the Apostles at the imperial capital.

[1] Oscar Cullmann, Peter: Disciple, Apostle, Martyr, trans. Floyd V. Filson (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2011), 114.

[2] Cullmann, Peter, 112-113.

[3] “The Ascension of Isaiah”, at britannica.com (accessed 9/24/2022).

[4] Ascension of Isaiah: Translated from the Ethiopic Version, Which, Together with the New Greek Fragment, The Latin Versions and the Latin Translation of the Slavonic, is Here Published in Full, ed. R.H. Charles (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1900), 24-26. Cf. Daniel O’Connor, Peter in Rome: The Literary, Liturgical, and Archeological Evidence (New York: Columbia University Press, 1969), 68. HathiTrust.

[5] Ascension of Isaiah, lvii.

[6] Charles, Ascension of Isaiah, lxvi. Cf. O’Connor, Peter in Rome, 68.

[7] O’Connor, Peter in Rome, 68. Charles is adamant: “From this passage it is manifest that the belief in Nero being still alive had already been abandoned”. He suggests two options: “Either Beliar must come in the form of the dead Nero , or Nero must be recalled to life by a Satanic miracle . The first course is adopted by the writer of the Ascension…” (Ascension of Isaiah, lxx).

[8] O’Connor, Peter in Rome, 69.

[9] O’Connor, Peter in Rome, 68-69. He concludes: “As is stands the information is too vague to serve as a strong argument for the martyrdom of Peter in Rome, but, on the other hand, the possibility that the passage does contain a cryptic reference to his martyrdom is so convincing that the evidence certainly ought to be proposed and considered” (p.70).

[10] Cullmann, Peter, 112.

[11] Ascension of Isaiah, xii.

[12] Cf. Cullmann, Peter, 79-113’ O’Connor, Peter in Rome, 61-86. On 1 Clement, the latter concludes: “Despite the objections of those who deny that Clement had any knowledge of Peter’s martyrdom in Rome…and those who see in I Clement 5 and 6 the beginning of the Roman legend of Peter and Paul, it is most probable Clement believed, on the basis of written or oral tradition or both, that Peter and Paul (in that order) died at about the same time in Rome during the persecution under Nero” (p. 86).