Introduction:

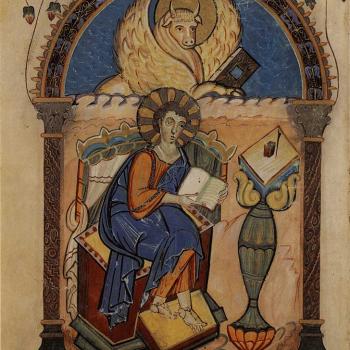

As the feast of All Souls Day (November 2nd) fast approaches in the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church, I figured a post (or two) on Purgatory was in order. In these articles, I wish to examine a passage from Mark of Ephesus’ (aka Markos Eugenikos) First Homily wherein he argues against the Catholic conception of the post-mortem “middle state”, which came to be known as Purgatory.

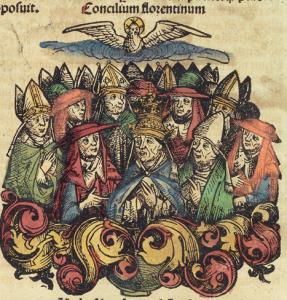

Mark of Ephesus (d. 1444) was perhaps the foremost opponent of the dogma at the Council of Ferrara-Florence (1438-1445), which attempted rapprochement between the Greek and Latin Churches. Although it ended in a declaration of union in the form of Laetentur Caeli, signed by the Byzantine bishops in attendance (save for Mark), it was ultimately repudiated by the Greek populace and by most of those prelates who had attended upon returning to the East. Thus the continued schism between Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christians.

Once a monk, Mark was elevated to the position of Metropolitan of Ephesus in c. 1436 by the Emperor John VIII Palaeologus, in preparation for the coming Council. Even though his theological formation is said to have been characterized as anti-Latin,[1] he is believed to have been sincere in his hope for reunion.[2] Western scholars have historically been critical of Mark, but this view has been challenged in recent years.[3] In a 2014 study, Fr. Christiaan Kappes “sought to tell a purposely positive story of Mark’s sincerity, erudition, reasonability, and humanity during the council itself”,[4] an endeavor in which he succeeded. With these facts in mind, we can proceed to introducing the immediate context of Mark’s First Homily. This will be followed by an excerpt of that document with a brief analysis of some of the ideas expressed in it (in part II).

Context:

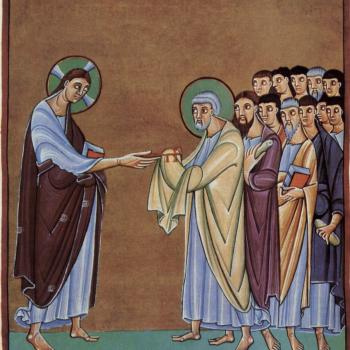

Before the official dialogues commenced at the Council of Ferrara-Florence, some preliminary discussions occurred between leading Greek and Latin prelates.[5] According to the Russian Orthodox (ROCOR) hieromonk Fr. Seraphim Rose, Mark’s First Homily was a response to a document produced by Giuliano Cardinal Cesarani (d. 1444) on the subject of Purgatory, and it “contains the most concise account of the Orthodox doctrine as against the Latin errors”. [6]

Claims of “Latin errors” aside, Fr. Joseph Gill, S.J. noted that Mark of Ephesus’ views on Purgatory were hardly representative of his contemporary Byzantines as a whole, as there was no monolithic view. He added that “the document that the Latins delivered to the Greeks after the first conference opened with a declaration of the teaching of the Roman Church, taken almost verbatim from the Profession of Faith made in the name of Michael VIII Palaeologus at the Second Council of Lyons [A.D. 1274]:

‘The souls of such as, truly penitent, shall die in charity before they have satisfied by worthy fruits of penance for their faults of commission and omission are purified after death by purifying pains, and the suffrages of the living faithful, that is sacrifices of Masses, prayers, alms-giving and other works of piety, avail to lighten penalties of this sort; those souls, however, which after the reception of baptism have incurred no stain whatsoever of sin, those too which after contracting the stain of sin have been purified either while still in their bodies or, after the manner noted above, after leaving them are presently received into heaven; but those souls which depart this life in a state of actual mortal sin or with only original sin presently descend into hell, to be punished however by diverse penalties; and nevertheless in the day of judgment all men will appear with their bodies before the judgment-seat of Christ, to render an account of their own deeds.’”[7]

The above then represents the Catholic conception of Purgatory ca. A.D. 1274, and reiterated in the preliminary discussions at the Council of Ferrara-Florence. It should be noted that the Second Council of Lyons just cited was a previously and likewise unsuccessful attempt at reuniting East and West. As we will see in part II, Mark of Ephesus did not reject the notion of a middle-state, or a post-mortem purification in his First Homily altogether, but rather some of the components of Purgatory as presented by the Latins he was in dialogue with during the preliminary discussions at Ferrara-Florence.[8] There some of the above will be recapitulated, and a citation of the First Homily will be produced and analyzed, highlighting some of the similarities and differences between what is found there and the dogma of Purgatory. Stay tuned!

[1] This and the information in the previous sentence from Encyclopedia Britannica Online, s.v. “Markos Eugenikos,” accessed October 23, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Markos-Eugenikos

[2] Cf. Joseph Gill, The Council of Florence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1959), 114; Christiaan Kappes, “A Latin Defense of Mark of Ephesus at the Council of Ferrara-Florence (1438-39),” The Greek Orthodox Theological Review 59, nos. 1-4 (Spring-Winter 2014): 164, https://www.academia.edu/4912818/_A_Latin_Defense_of_Mark_of_Ephesus_at_the_Council_of_Ferrara_Florence_1438_1439_

[3] Kappes, “A Latin Defense,” 161-164.

[4] Kappes, “A Latin Defense,” 189-190.

[5] Gill, Council of Florence, 118-119.

[6] Fr. Seraphim Rose, The Soul After Death: Contemporary “After-Death” Experiences in the Light of the Orthodox Teaching on the Afterlife (Platina: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2020), 197.

[7] Gill, Council of Florence, 119-120. The statement ‘or with only original sin presently descend into hell’, should be considered in light of the current Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraphs 1257-1261.

[8] Cf. Gill, Council of Florence, 119-125.