Before we left campus for Christmas, my colleague Rev. Dr. Dominique Robinson at Seminary of the Southwest gave me a brief education on Watch Night. Watch Night is a major feast and prayer event in the Black Church. It is also a rich study in the paradox of Christian freedom.

Before we left campus for Christmas, my colleague Rev. Dr. Dominique Robinson at Seminary of the Southwest gave me a brief education on Watch Night. Watch Night is a major feast and prayer event in the Black Church. It is also a rich study in the paradox of Christian freedom.

Watch Night in Black Church Traditions

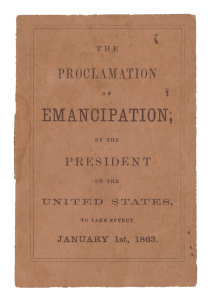

This Friday night, Black Churches around the United States will open their doors for a New Year’s Eve gathering. They will be celebrating the end of legalized slavery on January 1, 1863, when Lincoln’s Emancipation took effect. The services are, I imagine, quite different across denominations, but include prayers, hymns, a sermon, and a call to a watchman to report the approach of midnight. “Watchman, watchman please tell me the hour of the night,” the congregation sings out.

According to tradition, enslaved persons gathered on that first Watch Night to prepare their bodies, souls, and communities for a barely imaginable freedom.

I’ve written about Frederick Douglas’s struggle with white masters who outlawed Black-led worship. The Georgia Slave Code actually wrote this prohibition into law. In a land that prided itself on its foundation in religious liberty, Black Christian and Muslim believers often gathered in secret so they could worship. So there’s a powerfully subversive faith to the Watch Night tradition. On that night in the midst of war, when many slaves (not the ones in Texas, alas) heard the news of the approaching liberation, they gathered to do something that was in many cases still illegal. For a few more hours, anyhow. They gathered to pray.

John Wesley and Watch Night

When Dr. Robinson told me she’d be going to church on New Year’s Eve, I said, “Oh, you’re having a Watch Night service?” She told me my holiness roots were showing: I knew not to call it a New Year’s Eve service. And she was right about me. The tradition stems from John Wesley’s exploration of Puritan worship in the 18th century. I grew up in the Nazarene Church, a branch of the Wesleyan tradition. We had these services regularly on New Year’s Eve. I hadn’t known, though, about the way the practice had been adapted as a celebration of Emancipation.

Wesley’s version of the service was not particular to New Year’s night. If fact, it became part of the rhythm of revivalism of the Methodist movement. As he and other preachers traveled from town to town, they would often hold a midnight Service of Covenantal Renewal. Still, in London in particular, churches took up the practice as a way of welcoming in the New Year.

I said above that this tradition offers a rich study in the paradox of Christian freedom. I am referring to Wesley’s language in the liturgy, language modernized and still used in Methodist Watch Nights today. The theology centers around submission to Christ, and the practices of Christian servanthood.

Christ will be the Savior of none but his servants.

He is the source of all salvation to those who obey.

Christ will have no servants except by consent;

Christ will not accept anything except full consent

to all that he requires.

Christ will be all in all, or he will be nothing.

The obvious paradox here is that a service centered on submission to a Master was to become the liturgy for celebrating the casting off of masters. Is that the sort of paradox that Christians deem generative and appropriate, though? Or is it just a contradiction?

The Paradox of Christian Freedom

It is, I think, the first. The Christian faith centers on this paradox, what Saint Paul calls the true freedom of servanthood. Sarah Coakley has explored this paradox as a Christian feminist challenge to secular feminism. Submission, she says, is, despite everything, a worthy spiritual practice. And that’s because the one to whom we submit is the one who pours himself out in love for us.

The key to the paradox is, in fact, in Wesley’s admonition. “Christ will have no servants except by consent.” What is prayer, after all, but consent to the authority of another? The traditional postures—bowing, kneeling, closing of eyes and folding of hands—are ones that make one vulnerable. If the one to whom we prayed wanted to harm us, they could. And yet people pray. They submit to servanthood.

Christianity thus operates out of a deep anthropological challenge. It undermines the assumption that human freedom is to live without a master. Freedom is, rather, the consent to the Master we believe to be most trustworthy.

Servants of the True Master

Here, as in other ways, we are following the pattern of our Jewish siblings . The Fourth Commandment in Deuteronomy’s version of the Decalogue names the Exodus as the subtext of the Sabbath observance. “Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God brought you out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm; therefore the Lord your God commanded you to keep the sabbath day.”

The offense of Egypt is not slavery itself, astonishingly. Instead, it is idolatry. Pharaoh proclaims himself trustworthy enough to be master of humans. Only the God of Abraham is worthy of such submission. They rest, then, as a way of insisting that they are no longer Egypt’s slaves. Even Israel’s own slaves must rest on the seventh day: this is the command of their Master.

I think there is no body of believers anywhere that names, lives, and teaches this paradox so profoundly as the American Black Church traditions. These are a people whose ancestors cast off the yoke of slavery. They will celebrate this on Friday night by consenting to a life of servitude to the only true Lord.