Going Up

In Mark 11, Jesus goes up to Jerusalem.

It’s odd: the text repeats those directional adverbs—up and down—on several occasions. Cartographers point out that these are elevational directions rather than the cardinal sort. Jerusalem lies to Galilee’s south, so you can’t go “up” there. But it is higher, by some 2000 ft.

But I suspect that there’s more to those directional adverbs. Think of the way the Hebrew poet speaks: “I lift up mine eyes to this hills” “Who shall ascend the mountain of the Lord?” Elevation is metaphor, in the hymns of Israel, for praise. When we sing of hills, we remember what the Psalmist saw when he lifted up his eyes. Or what Moses found atop Sinai.

Worship, or praise, is where we rise up into the presence of God, offer our prayers and gratitudes, and sing of the mystery of a faithful burning love beyond all comprehension.

Worship in the Temple

It seems to me that Jesus’ purpose in going up to Jerusalem was singular. He was going up to worship. Mark even leaves open the possibility that Jesus had never actually been. This is a peak moment in his life. After all those years in the synagogues of Galilee, he’s going to enter the very beating heart of Israel’s communion with its savage yet faithful God.

I noted earlier what Jesus does when he first gets up there. He looks around the Temple. Then, as it’s getting late, he goes to Bethany. Perhaps to the home of Simon the Leper, his bed and breakfast for the Jerusalem stay. I’ll be back tomorrow, he seems to tell the Temple walls. I’ll be back to pray in this place.

He does return. But what he finds there is not the economy of divine grace, an exchange of blessings between God and God’s people. Instead, he finds a very earthly economy of coin and currency exchange.

There’s something strange here, something that requires the digging around of Bible scholars. I don’t know what it was about those coins that prevented true worship. But Mark is clear: something was off in the Temple.

When Worship is Off

Jesus had already picked up on this tension between the praying he longed for and the operations of the Temple leadership in the city. In chapter 10 he turns aside and tells his disciples what would happen when they got “up” there. It would be a kind of betrayal. Perhaps the initial Holy Week betrayal, before we get to Judas on Thursday.

There can be no misreading here that Jesus is rejecting the religion of Jerusalem. He’s coming to worship in the Temple. It’s a house of prayer “for all nations” he says, echoing second Isaiah as well as Genesis 12. The Temple of Israel is the place where the whole world learns to pray.

Unless we can’t. Unless our worship is off. We can’t begin to pray if we’ve lost track of the blessed exchange between divine beauty and human suffering. If we prefer instead the trading of metal coins.

For that reason, Jesus physically defends Temple worship. With his body. Mark doesn’t have him making a whip, but using his body like an offensive lineman to block people from bringing in their wares. And then, of course, flipping tables and chairs. As I put it in a post last fall, Jesus celebrates Hanukkah by going Maccabean on the money changers.

A Divine Thing Done Humanly

What’s he up to? Maximus the Confessor tells us that we can’t go through the gospel and decide which things Jesus does are human and which are divine. Everything that Jesus does is a human thing, but a human thing done divinely. And it’s all also a divine thing done humanly. He flips tables and blocks doors. That’s what a human with a body can do. What is the divine thing he’s doing at this moment?

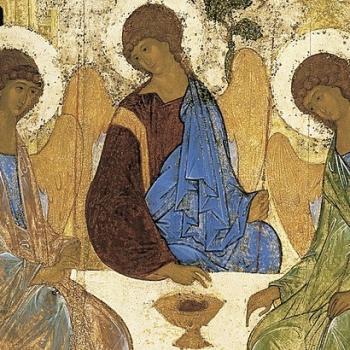

I’ve actually already said it. Worship. Jesus is the divine one whose very being is a gift from the one he calls “Father.” Moreover, Jesus’ Personality emerges in all eternity as Word of praise to that Loving Father. That Word is all he is! He is Worship, in his very Personhood. The Doctrine of the Trinity says that God is a loving economy of gift and praise. God is a Giving, a Receiving, and the Gift that passes between them.

And so the Incarnation is the story of that Beloved Receiver of Divine Gift, that eternal Word of Praise, emerging into history in the Galilean countryside. Coming of age while anticipating that great day when he will go up and worship in Jerusalem. The day that he will go up and do in a human and Jewish way what he is always doing in eternity in a divine way. That is: He will praise his Father in heaven.

Table Flipping as Trinitarian Worship

But then? He comes and finds that the blessed trinitarian exchange of grace beyond grace and love beyond love has turned into coin swapping. As if that’s all we’re made for.

Don’t think of Jesus’ response here first of all as an excessive but understandable human reaction. Think rather that it’s exactly what the Eternal Beloved Son would do, in a moment in which his very Personhood—a Personhood begotten for nothing but praise—was denied.

Oh, My Father in heaven, he would say, I would flip every table and chair from heaven to hell if it were keeping me from worshiping you.

And so, when he comes up to Jerusalem to do this divine thing called worship in a human way, those tables and chairs don’t stand a chance. Just like Judas Maccabeus before him, he explodes with rage when he finds the house of worship inhospitable to Jewish ritual. That first Judas was a figure of incarnation in this sense. He was a human performer of the divine act of praise.

The Body that Reopens the Way

This act of Jesus leads to his death. This is the reason that we can say something so absurd that Paul calls it foolishness. We can say that dying is also a fitting thing for the Godhuman to do. It’s fitting in a world hostile to worship to lay one’s life down to that hostility. Jesus uses his body to reopen the way to true prayer. That’s the story of the cleansing of the Temple; it’s also the story of the cross.

Conversation with my colleagues Nathan Jennings and Dan Joslyn-Siematkoski have helped me contemplate the Temple cleansing in Mark.