By Rev. Msgr. Kieran E. Harrington

This past Wednesday I buried a friend. Actually, she was much more than a friend. She was a companion, a colleague, a role-model, and a religious sister.

She was also my sister. The Lord called her home, on the Feast of All Saints, twenty-eight years after she first professed vows of poverty, chastity and obedience.

I am ashamed to say that for most of the eight years we were assigned together, she was simply an employee in a habit. Don’t misunderstand me, we got along and worked well with one another, but I never took the time to get to know this woman who, I would discover too late, was simply exceptional.

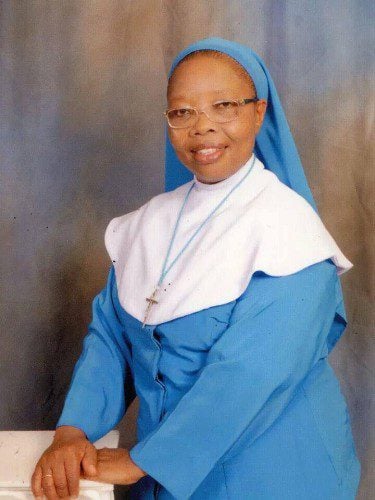

Who was this woman, who so profoundly touched the lives of so many people — young and old — that they came from all over Brooklyn and beyond, to see her in the hospital, only to end up being consoled by her, even as she lay dying?

Sister Juliet Duruanyaoha was born on April 4, 1955 in Lagos, Nigeria. She had a twin sister and seven other siblings, all growing up in a rural and impoverished village in Imo State. The Biafra War left its scars upon her; the conflict claimed over a million civilian lives — many of whom simply starved to death — and her own education was interrupted.

Despite these challenges, she persevered, completed her education and joined the Discalced Carmelites. She desired a life of quiet contemplation, but the enclosed separation that defines the monastic life proved to be a great hardship upon her family; out of love for them, Juliet left the cloister and entered a community formed out of the ravages of war, the Daughters of Divine Love.

The Community was founded in 1969 by Bishop Godfrey Mary Paul Okoye, formerly an Irish Holy Ghost Father, as a means of protecting the young women and girls from the brutality of rape during the Civil War. The experience of Divine Love manifested by the good and courageous Bishop led many of those young women to commit themselves to Christ, as religious women, after the cessation of violence.

Mary Juliet thrived in the convent. Indeed, she was particularly competent and was posted to serve as secretary to the local Bishop. She quickly became a surrogate mother to the young boys who sought to be priests, and resided in the Bishop’s home.

As the community expanded Sr. Juliet was asked to be among the first sisters to go to the United States, as a missionary. Her first apostolate in the States was as a teacher at St. Theresa of Avila in the Prospect Heights section of Brooklyn. She later would be posted to Saint Joseph Church, and had been there for eight years when I first encountered this short, round, vivacious Nigerian nun.

The parish was poor and chaotic; she worked within it six days a week, and was paid for only one. Officially, she ran a CCD program with pathetically few children. Unofficially, she was the Chaplain to the local nursing home, visitor-in-chief for the sick of the parish, counselor for the older ladies, and mother to children facing many hardships.

The one area where Sister was not particularly proficient was administration. Paper work was routinely lost, left incomplete or undone. Frankly it drove me crazy. I fretted that as our parish grew this would become an obstacle to newly arriving families, who would expect order. My anxiety was be compounded by the fact that each week, as we tried to clean the Church and rectory, items I threw into the garbage would find their way back into the office, tucked away into a new place.

Shrugged-off paperwork and reclaimed junk; clutter all around. It made me nuts; it was how she rolled.

I should have been more attentive, that first week in September, when Juliet complained about arthritis, and stayed home at her convent for a week. Neither she nor I knew that she was pivoting toward Calvary — that what we believed to be arthritis was actually a cancer, eating away at her entire body.

Five weeks ago, when I told her she was dying, we had some decisions to make. Missionaries are buried where they fall. For Juliet, the thought that her aged mother might not be able to mourn her compelled her to return to Nigeria.

The travel was perilous. Juliet was dealing with bilateral blood clots in the lungs; more clots were forming in her legs. There was a tumor in the spine, another in her lung, more on her ribs and God only knows where else. On the Saturday before she was to leave for home, her hip was fractured; her bones had become so brittle that gentle massage, meant to lessen her agonizing pain, only brought more injury.

That she would survive the arduous trip seemed doubtful, but Juliet believed.

She did fly home on October 20, arriving in Enugu on the 21st. Despite the exhausting journey Sister Juliet would appear to her sisters and family as being in the picture of health. But the rally was only to last for a day or two, before Calvary truly beckoned.

On November 1, prior to celebrating Holy Mass, I called to wish Sister a blessed anniversary. By now her only response were grunts of pain; her voice was completely gone. Sister believed the Lord would heal her in his own fashion, as she stood before the Altar, that He was working that miracle, and soon it was time for her to return home.

A few hours later, I asked the people at Mass to pray for Sister Juliet as she entered the final agony. As soon as I returned to the rectory the phone rang, it was her traveling companion and friend Sister Nnachibe telling me that Juliet had entered eternity.

The compound of the Daughters of Divine Love is an oasis yet, like the country of Nigeria, it is a work in progress. The Chapel is massive yet simple. As the marching band played Sister Juliet Duruanyaoh into the church, she was greeted by several hundred of her sisters. With blue veils, white habits and beautiful brown skin, they welcomed Juliet home to the novitiate where her life as a bride of Christ had begun. The music was an enchanting combination of traditional chant and indigenous hymns. Soon we prayed for her; the Office of the dead.

Still yet more sisters arrived, and by the time we were ready to celebrate the Rites of the Church we had about seven hundred sisters in the Chapel, fifty priests and two bishops. Juliet had been in the United States for almost fifteen years. Most of the sisters and priests were so young that they had not known her personally, but to each she was a true sister.

As we lowered her to the depths, and laid a blanket of dirt over her body, her family broke down. They had learned only ten days earlier that their daughter and sister was sick. They were impoverished people from the bush and the spectacle, and the loss, was became overwhelming.

Arriving home, the first thing I saw as my car pulled up in front of the rectory was a beaten-up desk at the curb, waiting to be carted away as trash. Juliet would have ransomed it, because she understood — in a way I have only begun to appreciate— the profound poverty so many live with each day. This child of unimaginable poverty was missionary to a people so accustomed to material wealth they saw old, worn things as “clutter and junk”, disposable and not worth saving.

This week, celebrating mass with the people of Saint Joseph’s, I finally understood this contemplative little Nigerian nun, with her round figure and broad smile. She had cultivated a deep interior life and simply invited others in to join her in a great love affair with God, where no one and nothing was junk or clutter — beyond saving, or fit only for the trash heap.

I am grateful that Sister Juliet allowed me to walk with her these last months, to draw nearer to her, and glimpse the life of a saint. She may not have been perfect with the paperwork, but she knew what mattered. She was in love with Jesus Christ, and her love was contagious.

My prayer is that I have been infected.

Msgr. Kieran E. Harrington is Vicar for Communications for the Diocese of Brooklyn, and Administrator of the Co-Cathedral of Saint Joseph. He also hosts the Catholic radio program “In the Arena”, on 710 WOR Radio

Msgr. Kieran E. Harrington is Vicar for Communications for the Diocese of Brooklyn, and Administrator of the Co-Cathedral of Saint Joseph. He also hosts the Catholic radio program “In the Arena”, on 710 WOR Radio