by guest writer Gregory Moomjy

Bernstein’s Mass was written for the opening of the Kennedy center in Washington D.C. As such, Bernstein wanted to write a piece that would reflect something essential about President Kennedy. Bernstein chose to focus on the president’s faith because to date he is the only Catholic president in U.S. history. However, the piece is not a straightforward setting of the Catholic liturgy. Rather, it is a theater piece built around the ritual of the Catholic mass. At its center is the celebrant, who throughout the course of the piece has his faith tested as he takes on the concerns of his parishioners as well as his own outlook on religion.

Tensions come to a head when the celebrant drops and shatters a chalice. This brings about the final section of the piece which begins with a sort of mad scene from the celebrant as he confronts the disturbance to the ceremony. It is a kind of mad scene that brings the celebrant’s crisis of faith to the foreground. The libretto deals directly with the celebrants changing views of faith in the opening lines of the mad scene. He notes that it is strange that red wine is not truly red but brown, and that glass shines brighter when broken. He is transitioning from a literal ritualistic view of faith to one more grounded in spirituality and individuality. Therefore, it becomes a perfect representation of the mass both as ritual and as something with deeper philosophical, psychological, and emotional significance.

Bernstein uses the mass to reflect and comment on issues contemporary to the 60s and 70s, such the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War. The libretto, written by Steven Schwartz of Godspell and Wicked fame, accomplishes this by contrasting selections from letters from St. Paul with letters reflecting modern day issues, like the draft and incarceration.

At the Ravinia Festival, outside of Chicago, a recent production of Mass starred Baritone Paulo Szot—who became famous when he sang the lead in South Pacific at Lincoln Center theater a decade ago. It was also conducted by Marin Alsop, a protégée of Bernstein. This performance was updated so that the reading of letters would include correspondence written by the larger community and thus reflect contemporary concerns, such as letters on immigration and border patrol.

Bernstein was Jewish, but he was no stranger to religious music. His Caddish Symphony uses the Jewish prayer to honor those lost in the camps in World War II. While other settings of the liturgy might explore the believer’s relationship with certain key aspects of Christian theology—such as Verdi’s requiem and Judgement Day—Bernstein’s Mass takes a direct look at the mass itself and what it means to participate in it; both as a celebrant and as a member of the congregation. Musically, Bernstein is known for his ability to adapt various genres of pop music into the classical style, as seen for instance in his evergreen West Side Story. Mass follows in this tradition. And while it is now recognized as his best work, at the time of its premiere critics did not know what to make of it. It was viewed as too overblown and containing a hodgepodge of musical styles.

At the time he wrote West Side Story, Bernstein used operas like Mozart’s The Magic Flute as his model. The Magic Flute is technically what the Germans call a Singspiel (a sung play), in which dialogue is interspersed with arias and ensembles that feature certain hallmarks of classical music, such the development of themes. However, it seems more appropriate to say that Bernstein wrote in the style of operas like Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess or Puccini’s La rondine. In the case of Gershwin, Porgy and Bess amalgamates jazz and blues into classical music. And Puccini’s operetta does the same thing with popular dance styles like the tango and foxtrot. Mass encompasses a range of musical styles, including atonality, soft rock, pop, as well as marching band music. At first glance, it is easy to see why critics at the premiere were confused by the blend of styles, but Bernstein actually deploys each genre of music with great aplomb, creating a contrast between the outward ritual of the mass and its inward spirituality.

The parts of the catholic mass can be divided into two groups: the ordinary and the proper. The ordinary consists of five parts: the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei, with the possible inclusion of the Ite Missa Est at the end. The texts for these sections never change. Consequently, they are the sections of the mass that composers set to music most frequently. In Mass, it is these sections which Bernstein sets to atonal, foreboding music. In the case of the Kyrie, which opens the work, the stringent atonality gives way to the celebrant’s “Simple Song,” sung in English to accompaniment reminiscent of Joni Mitchell. This opening sets up the main conflict of the piece, in which the celebrant struggles to make the purity and emotionality of the mass as an expression of faith clear over the dusty ritual, which the liturgy has accrued over the centuries. In the following section, the adult choir onomatopoeically sings a melody of ringing bells reminiscent of a 50s infomercial. At first sight, this may be confusing. But Bernstein also uses similar music for the ensemble scenes in his opera, Trouble in Tahiti. There, such banal music represents the tedium of life in suburbia. Therefore, here, such music represents the tedium of celebrating the ritual of mass without faith.

Mass includes two choirs: a children’s choir and an adult choir. The latter of which principally comes into play when voicing the contemporary issues that threaten faith. Whereas the children’s choir is much more in line with the celebrant, who sings simple tuneful diatonic music. This can be seen in the Gloria. Here, both the adult and children’s choirs sing in Latin. But the adult choir includes much more jagged rhythms and English lyrics such as “half of the people are stoned, and the other half are waiting for the next election / half the people have drowned, and the other half are swimming in the wrong direction.”

While there are many recordings of Bernstein’s mass, it is really a work that needs to be seen. This is because there are many orchestral interludes. And as seen by the recent production at The Ravinia Festival, Paulo Szot’s celebrant uses these interludes to interact with his parishioners and demonstrate the struggle of faith that he and his flock were enduring. One interlude is reminiscent of Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings,” the piece used in nearly every movie as the soundtrack for major catastrophes.

Despite its lackluster critical reception upon its debut, Mass is one of Bernstein’s greatest works. Its examination of the interplay between faith and the world at large is just as powerful today as it was at its premiere.

If we learn anything from Mass, it is that the big questions that society faces at their core do not really change. More importantly, the faithful cannot divorce their faith from morality in everyday life. The difficulty of the mass is to live it every day and not just in church on Sundays. Faith untested is not faith at all.

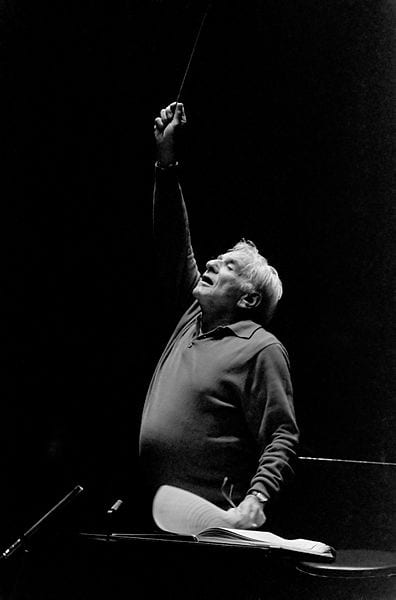

image credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leonard_Bernstein_(1987).jpg