Guest Writer: Pilgrim

Guest Writer: Pilgrim

Introduction

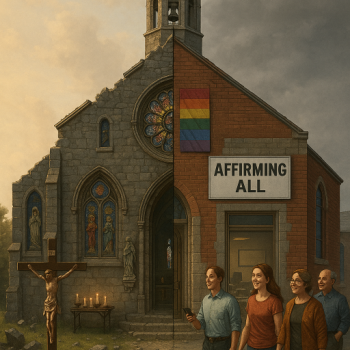

Many Catholics today find themselves disoriented by conflicting theological voices, unsure of what the Church truly teaches. This confusion is not always accidental. The Magisterium has warned against “studied ambiguity” used to mislead the faithful under the guise of orthodoxy [1]. In many cases, the use of seemingly faithful language while subtly altering its content lends itself to misinterpretation or even manipulation.

A theological trend often described as progressive – one that emphasizes historical conditioning, lived experience, and cultural adaptation – has emerged as a key driver of this phenomenon. While often motivated by pastoral concern, such an approach risks treating doctrine as fluid rather than fixed, reframing it as one option among many rather than the authoritative truth revealed by Christ and His Church.

Pope Francis’s pontificate introduced a significant shift: from the doctrinal clarity of his predecessors to a pastoral style rooted in mercy, encounter, and inclusion. Many welcomed this approach as more effective in reaching the wounded and marginalized. Many sincerely believe that focusing on accompaniment and discernment can draw people more deeply into the life of grace. Yet this same pastoral style, imprecise in some of its formulations, has also created space for theological reinterpretation. Whether intended or not, ambiguity can be misused by those seeking to change doctrine under the guise of development.

Theological Shifts and Latin American Influences

St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI upheld a theology rooted in metaphysical realism, objective truth, and moral clarity. His is seen especially in Veritatis Splendor and the theology of the body. In contrast, Pope Francis draws upon Argentine Teología del Pueblo, a strand of Latin American theology that emphasizes cultural context, praxis, and popular religiosity. This tradition, shaped by figures such as Juan Carlos Scannone SJ, views el pueblo, the people, as bearers of a unique spiritual wisdom not captured by academic theology [2].

Pope Francis’s Evangelii Gaudium speak of the “privileged place of the poor” and calls for the Church to be “bruised, hurting and dirty because it has been out on the streets” in solidarity with them. It adds, “We need to let ourselves be evangelized by them. The new evangelization is an invitation to acknowledge the saving power at work in their lives and to put them at the center of the Church’s pilgrim way” and uses the imagery of a “bruised, hurting and dirty” Church that goes out to the peripheries” [3].Fratelli Tutti echoes this emphasis on a culture of encounter and universal fraternity. It discusses the need for a universal love that transcends borders and promotes the dignity of every person, which is foundational to a “culture of encounter” [4]. Writers like Zanatta specifically link Pope Francis to this “Theology of the People.” [5].While this emphasis has brought renewed attention to the dignity of the poor, it also risks locating theological authority in subjective experience rather than divine revelation.

From Revelation to Experience

The Catholic tradition understands revelation as the definitive self-disclosure of God in Christ, transmitted through Scripture and Tradition and interpreted by the Magisterium [6]. Progressive theology, however, tends to prioritize human experience, arguing that it can yield new insights into truth. This leads to the claim: “The Church teaches X, but our experience suggests Y.” While experience has a legitimate place in theological reflection, when elevated to the level of doctrinal authority, it undermines the deposit of faith [7].

This shift away from metaphysics compounds the problem. Catholic theology, particularly in the Thomistic tradition, insists that truth about God and man is objective, knowable, and revealed in Scripture. But historicism, which sees doctrine as valid only within its historical context, fosters relativism [8]. As Pius XII warned, such “dogmatic relativism” fractures the coherence of faith and invites error [9].

Ambiguous Language and Doctrinal Drift

Language is a key instrument in promoting this theological shift. Words like “development,” “pastoral,” “inclusion,” and “dialogue” are retained, but redefined. “Development” is sometimes invoked to mean reversal rather than deepening of truth. “Pastoral” is framed as the opposite of “doctrinal,” suggesting that compassion justifies deviation from moral norms. “Inclusion” is presented as affirmation without conversion, and “dialogue” as permanent hesitation rather than a path to truth.

Even the sensus fidei is reimagined; not as the faithful’s instinct for truth in communion with the Magisterium, but as a kind of democratic process whereby doctrine evolves through popular consensus [10]. Likewise, appeals to the “spirit of Vatican II” are frequently used to justify positions never articulated by the Council itself, lending an appearance of legitimacy to views that depart from tradition [11].

The Hermeneutic of Rupture

These tendencies mirror what Pope Benedict XVI called the “hermeneutic of rupture”: an interpretive lens that sees Vatican II as a break from the Church’s past [12]. This approach pits a “post-conciliar Church” against everything that preceded it, dismissing centuries of Magisterial teaching as obsolete. By contrast, the Church insists on a “hermeneutic of continuity,” reading the Council in harmony with the whole tradition. Vatican II was pastoral in its approach, not doctrinally innovative in substance.

The Death Penalty Revision

An example of contemporary ambiguity is found in the 2018 revision of Catechism §2267, which declares the death penalty “inadmissible” [13]. Pope Francis insists this is not a contradiction of past teaching but a development based on a “new understanding of Christian truth” [14]. Yet the claim that prior justifications are now “clearly contrary” to Christian truth raises concerns. How can continuity be maintained if previous teachings are no longer valid?

John Paul II had reaffirmed that the death penalty was not intrinsically evil, though he judged its use “very rare, if not practically non-existent” [15]. Francis, however, argued that it now violates the inviolability of human dignity in all circumstances. The CDF, while affirming continuity, concedes that this teaching relies on insights that were previously undeveloped [16]. For many, this move appears less like organic growth and more like reversal.

Amoris Laetitia and Pastoral Subjectivity

Amoris Laetitia (2016) presents a similar tension, especially in Chapter Eight, which deals with Catholics in “irregular unions.” It acknowledges that not all individuals in these situations are equally culpable and calls for pastoral discernment [17]. Footnote 351, states that the sacraments may be given to people “in an objective situation of sin” due to mitigating factors [18].

While the document repeatedly affirms that doctrine remains unchanged, many interpret this language as relaxing the Church’s prior discipline. Both Familiaris Consortio and Sacramentum Caritatis had reaffirmed that divorced and remarried persons must live in continence to receive Communion [19]. Pope Francis later confirmed the Buenos Aires bishops’ interpretation, allowing Communion in some cases without continence, as the only valid reading [20].

The style of Amoris Laetitia, emphasizing case-by-case discernment, effectively shifts moral theology from universal norms to subjective application. For many theologians, this represents a deeper change: a move from revelation as fixed truth to a dynamic process evolving through lived experience [21].

The Impact of Ambiguity

These shifts have real pastoral consequences. In some dioceses, sacramental access is granted to individuals in irregular unions without conversion or a change of life. The resulting fragmentation has caused widespread confusion.

If doctrine is merely evolving interpretation, the Magisterium is no longer the guardian of immutable truths but becomes a facilitator of shifting norms. The Synod on Synodality’s inclusion of lay voting members on doctrinal matters has raised further concerns about this democratisation of authority [22].

The Use of Ambiguity

While Pope Francis did not formally contradicted any defined teaching, his open-ended and pastoral tone allowed certain theologians and bishops to interpret ambiguity as license for change. Terms like “integration” and “discernment” are invoked to support mutually incompatible conclusions. In some cases, this may reflect sincere but misguided attempts to apply the Gospel to wounded lives. In others, it appears to be a deliberate strategy to advance theological agendas under the cover of papal legitimacy.

Restoring Clarity

How can the faithful remain grounded amidst this confusion?

- Seek Precision: Clarify the meaning of terms. Ask whether “development” means a deeper understanding or doctrinal reversal.

- Anchor Discourse in Authoritative Sources: Return to Scripture, the Catechism, and conciliar documents, not just contemporary trends [23].

- Discern True Development: As John Paul II warned, openness to the world must never become accommodation to its values [24].

- Identify the Source of Authority: Does the argument rest on divine revelation or sociology?

- Unite Truth with Charity: Genuine mercy never denies the demands of truth. As Benedict XVI wrote, “charity in truth” is essential for authentic love [25].

- Respect the Magisterium’s Scope: Even non-infallible teachings call for respectful assent [24].

- Maintain the Analogy of Faith: Catholic teaching is coherent. No truth stands in contradiction to another [27].

A Spiritual Pathway

This task is not merely intellectual but spiritual. To resist confusion, the faithful must cultivate:

- Humility, in submitting to the Church’s wisdom.

- Patience, remembering that the Church thinks in centuries.

- Prayer, especially through immersion in Scripture, the Catechism, and the life of the saints.

As Pope Leo XIII reminded us, the priest’s chief study must be “the science of the saints” [28].

Conclusion

Pope Francis’s pastoral style reflects a genuine desire to reach the wounded, the alienated, and the forgotten. His emphasis on mercy and inclusion has resonated with many. Yet the linguistic and theological ambiguity in key magisterial texts has led to diverging interpretations that challenge unity and continuity.

The Church’s task now is twofold: to preserve the heart of this pastoral mission while reaffirming the clarity of doctrine and the objectivity of truth. Without this balance, she risks losing not only coherence but credibility. The future of Catholic moral theology depends on how we respond to this tension with fidelity, charity, and clarity.

Footnotes

- Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons, October 1, 1986, sec. 14.

- Juan Carlos Scannone, “Popular Culture: Pastoral and Theological Considerations,” Lumen Vitae 32 (1977): 161–170.

- Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium §198, §49

- Pope Francis Fratelli Tutti §24–25

- Loris Zanatta, Pope Francis and the Theology of the People (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2023), 12–20.

- Second Vatican Council, Dei Verbum, 1965, sec. 10.

- Second Vatican Council, Dei Verbum, 1965, sec. 4; Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed., sec. 66. See also Pope Paul VI, Mysterium Fidei, September 3, 1965, sec. 25.

- Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, In Defense of the Catholic Doctrine on the Church Against Certain Errors of the Present Day, June 24, 1973, sec. 5.

- Pius XII, Humani Generis, August 12, 1950, sec. 14.

- International Theological Commission, Sensus Fidei in the Life of the Church, 2014, sec. 84.

- Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Circular Letter Regarding Some Sentences and Errors from the Interpretation of the Decrees of the Second Vatican Council, July 24, 1966, sec. 1.

- Benedict XVI, Address to the Roman Curia, December 22, 2005.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed. (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1997 – revised 2018), sec. 2267.

- Francis, Address to Participants in the Meeting Promoted by the Pontifical Council for Promoting the New Evangelization, October 11, 2017.

- John Paul II, Evangelium Vitae, March 25, 1995, sec. 56.

- Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Letter to the Bishops Regarding the New Revision of Number 2267 of the Catechism, August 1, 2018, sec. 3.

- Francis, Amoris Laetitia, §§300–305.

- Ibid., footnote 351.

- John Paul II, Familiaris Consortio, 1981, §84; Benedict XVI, Sacramentum Caritatis, 2007, §29.

- Francis, Letter to the Bishops of the Buenos Aires Region, September 5, 2016, Acta Apostolicae Sedis 108 (2016): 1071–1074.

- Michael R. Candelaria, Popular Religion and Liberation (New York: Suny Press, 1990), 45–48.

- General Secretariat of the Synod, Regolamento for the XVI Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops (2023), Art. 12 §1.

- Second Vatican Council, Dei Verbum, 1965, sec. 10.

- John Paul II, Address to the Bishops of Great Britain, March 17, 1992.

- Benedict XVI, Caritas in Veritate, June 29, 2009, sec. 1.

- Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium, 1964, sec. 25; CDF, Donum Veritatis, May 24, 1990.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed., sec. 114.

- Leo XIII, Providentissimus Deus, November 18, 1893, sec. 14.

Thank you!

If you liked this article, please leave your comments below. I am very interested in your opinion on this topic.

Read The Latin Right’s other writing here.

Please visit my Facebook page and IM your questions (and follow my page) or topics for articles you would like covered.