It is late spring still. So much of the news has been bad. The natural world around us here in Connecticut is beautiful, but global melancholy can interrupt local joys. This is the first year in which I attempted to make vin d’orange. It’s a wine made from rosé wine, vodka, sugar, and sour oranges. In February, when the oranges are in season, you store this mix in a big glass vat for a month before transferring it to bottles. A friend and I opened the first one. It was unlike all the others because the bottle was not full. We placed what was left in its own bottle, only reaching halfway up. It fizzed explosively when we opened it. Sediment and the milky mother at the bottom flew through the mix, electric with bubbles. It made a mess, but when it settled down we drank it and it was delicious. A defiant gesture in some ways: to wait, to save, to hope, and, even when things go a little awry, to make time for the enjoyable. In winter, to cut fruit and store it in the hope both it and us will be here in several months. To be aware of seasonal changes, decay, and the effect on our own spirit. These can be the acts that refresh us when the news around us is awful.

These attempts remind me of one of my favorite poets: Jorie Graham. So many of her poems begin out of the act of a common chore, a visit to a museum, or reading. One of her most famous poems, “The Geese” begins with hanging laundry out to dry. I fell in love with Graham’s poetry when I was a bit too young to grasp her work. I was 12 and her Pulitzer Prize winning collection The Dream of the Unified Field had just been published. It was a collection of poems from her first five collections of poetry. I needed to order it through Interlibrary Loan and the cover, a painting of Eve emerging from Adam’s rib led by the hands of God, fascinated me deeply. The shape of the poems on the page was enticing. Small, dancing lines in the early work led to vast, expansive lines in the later collections. A dedicated, almost fanatical student of the French language, I relished her poem “I Was Taught Three” about growing up trilingual. “A Feather for Voltaire” with its gorgeous beginning “The bird is an alphabet, it flies / above us, catch / as catch can…” lingered with me.

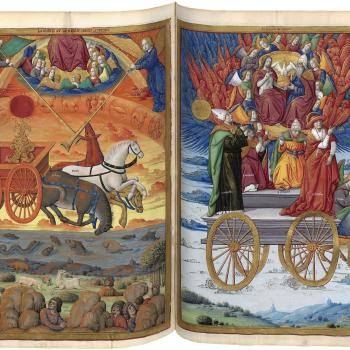

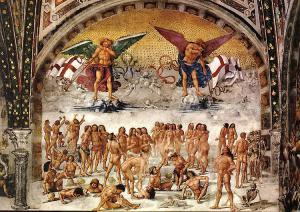

Yet one poem, from Graham’s breakthrough second collection Erosion, has never really stopped testing me in hard global times (or hard local times for that matter): “At Luca Signorelli’s Resurrection of the Body.” The painting, made around 1500, depicts bodies rising from their graves to face judgment.

Graham’s poem interrogates what it means to enter another body or to re-enter one’s own body”

they hurry to congregate

they hurry

into speech, until

it’s a marketplace,

it is humanity. But still

we wonder

in the chancel

of the dark cathedral,

is it better, back?

Graham unpacks what should be the most eschatologically significant moment in these people’s lives. Rather than stand in awe or in prayer, “they keep on / arriving, / wanting names, / wanting / happiness…” The poem understands that to have a body is to have longing, to enter into a body is to enter into longing. The observers of the painting long to tell the figures inside “that there is no/ entrance, / only entering…” No way into another body, no way really into our own, just the act of attempting of doing it where no clear entryway exists.

I once taught this poem to students at the College of the Holy Cross as part of an introductory course in critical reading and writing about poetry. The end of the poem left many students with moist eyes. Graham shifts focus from the painting to Signorelli himself. Signorelli understood the form of the body because he dissected the body. He studied and cut into the body to better represent it. The poem closes with a description of how Signorelli, when his only son died violently, laid him out on a table, awaited perfect light, and then dissected him carefully. The poem closes:

It took him days

that deep

caress, cutting,

unfastening,

until his mind

could climb into

the open flesh and

mend itself.

So much of our faith leads us out of the body. When Ficino offered a Platonic Theology in the fifteenth-century, just a few decades before Signorelli’s painting, he continued a pattern in Catholic thinking going back to Paul and Augustine: the rejection of the world and of the body for higher contemplation and meditation. Graham knows transcendent contemplation and higher forms well. She writes about them frequently. But this poem brings us back to the body and the world. In the Catholic tradition, body and spirit work together. We can defy the world in prayer and in meditation, but we exist in our faith only in the presence of Christ’s body. The discomfort between body and spirit animates Signorelli’s painting and Graham’s poem. To deal with the unthinkable and the tragic, the failures of the mortal world, we may begin by entering the body more fully. There is no entrance to another world while we are still on it. We can only get better at entering and in that entering, try to heal ourselves in facing another and in facing our own pain.