So often in prayer, we hope for yes. A yes to our wishes. A yes to ourselves. A yes to tell us that, yes, indeed we are on the right path. We are deserving. We are fundamentally good. Yes, we are talented. Yes, everything will be ok. Yes, despite our failings, we will still find happiness. Yes, the kids will be ok. Yes, the future will bring good things. Yes yes yes. It can be done. It will be done. We will get there in the end. We shall overcome. We shall win.

Yet, it is in our “no” that the prayer life begins. A no to distractions. A no to despair. A no to cheaper, easier fixes. A no to ourselves. A no to our desires. A no to the world around us. It is also in this no that the rebellious and radical nature of the gospel can come to fruition. I thought of this turning to a stunning piece of writing published this year.

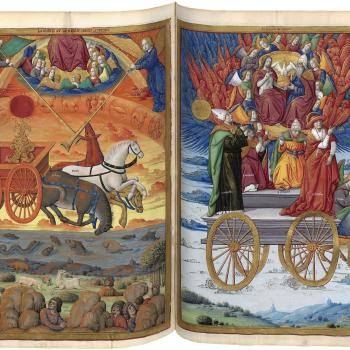

“History is full of people who just didn’t.” This is from Anne Boyer’s opening essay “No” from her spectacular book A Handbook of Disappointed Fate. This is not just an insight for grand, historical gestures:

“Sometimes our refusal is in our staying put. We perfect the loiter before we perfect the hustle. Like every toddler, each of us once let all adult commotion move around our small bodies as we inspected clover or floor tile. As teens we loitered, too, required Security to dislodge us, like how once in a country full of freely roaming dogs, I saw the primary occupation of the police was to try to keep the dogs out of the public fountains, and as the cops had moved the dogs from the fountains, a new group of dogs had moved in. This was just like being a teenager at a mall.”

Though light vagrancy may not seem the occupation of the prayerful subject, it is in fact the prerogative of the person at prayer to say no and stay put. To stay in the moment. To refuse distraction and the demands of the human flow of movement. To find some other space. For Boyer, poetry can often enact such a refusal and in its refusal can “protect” a yes.

“Words are useful for upending the world in that they are cheap, ordinary, portable, and generous, and they don’t mess us up too badly if we use them wrong, not like marches or machetes…” Boyer understands that poetry exists beyond words but her point here is an important one. Action and the via activa present stakes that are often beyond the full range of our readiness. Prayer without action is worthless, but action without prayer has no direction, no sense.

In my academic work, I knew of many people who believed their written work, their thinking was their activism. That just by doing the work of language they were uplifting the oppressed. They weren’t. Similarly, prayer alone can only do so much, but that much has value. It is the first no that leads the thinker to new possibilities and new rebellions against the world.

We spend much of our lives waiting for a yes, but we can do so much by starting with a prayerful no of our own.