On our last full day in France (we’re settled back in the Nutmeg State now, even if our heads are still a bit on French time), we visited the Pantheon in a hilly location in Paris not far from the Sorbonne and the Collège de France. It’s a heady sort of neighborhood, full of bookstores and small cinemas showing old films. It’s the sort of place where you can be tricked into thinking all anyone does is read, go to films, and sip wine.

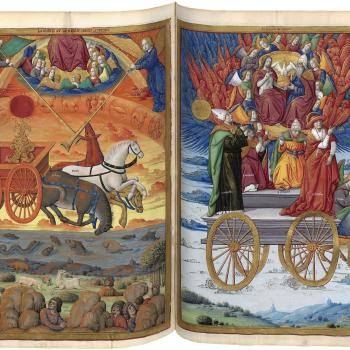

In contrast, the Pantheon is a place of grand seriousness. It was first established as a cathedral, meant to match the scale of St Paul’s in London and St Peter’s in Rome. It succeeded in this aim, it’s massive. It celebrates the legacy of Saint Genevieve, the Patron Saint of Paris whose works in the fifth and early sixth centuries helped bring comfort to a city upset by plagues, famine, and war. The large painted frescoes of her life are stunning.

Yet, on top of these religious roots a more secular tree has been forced. The Pantheon is a national necropolis, a resting place for France’s most celebrated residents as well as a tangible celebration of the French Republic. But, despite the large statue celebrating the National Convention where an altar should be, there are ghosts everywhere.

I felt compelled to go during this trip because I had never visited the Pantheon before. I wanted to see, specifically, the resting place of Victor Hugo. I am not a massive fan of Victor Hugo’s work (Ronsard, Du Bellay, Labé, de Musset, and Racine are more my French favorites), but I feel, especially in 2018, that Hugo is important. He was, perhaps the last example in France, an author who reached stratospheric and democratized cultural importance. He was a central and singular voice in French letters for much of the nineteenth century and his works were devoured across class and educational lines. Les Misérables, a massive tome, is among the most widely read novel in France and the musical based on it, most popular in its English language form, has spread the work throughout the Anglophone world and beyond. We need more writers who can so fully capture a nation’s attention. Who can make joyful readers of us all.

When I was a young student of French, we were required to memorize Hugo’s poem to his daughter who drowned in early adulthood, “Demain, dès l’aube” (Tomorrow, right at sunrise). It’s a poem in which he visits her grave. I still have it memorized in French. I’ll translate it in my head for you:

Tomorrow, right at sunrise, I will go.

Do you see? I know you are waiting for me.

I will go by the forest. I will go by the mountains.

I can never stay away from you for very long.

I will walk with my eyes focused on my thoughts

Without seeing anything outside, without hearing any noise.

Alone, my back bent, my hands crossed,

Sad: day for me shall be like the night.

I look not look at the setting sun

nor the sailboats in the distance heading to Harfleur

and when I arrive, I will put on your tomb

some holly and heather in flower.

As a fifteen year old French student, I admired the language and the challenge of learning the poem. I didn’t believe my teacher when she said I would never forget the poem, but it’s 18 years later and I haven’t. As a father, the poem upsets me now much more than it could then, but I understand it more deeply. The connections that fatherhood brings. The connection Hugo still has.

The Pantheon was built for such an experience. The dead, saints, sinners, and thinkers all together, held in a cavernous space to inhabit. As we walked through the crypt, we saw the resting places of Pierre and Marie Curie, Victor Hugo, Voltaire, Rousseau, and a special plaque to Antoine de Saint-Exupéry who’s body lies somewhere hidden after his plane crashed almost 80 years ago.

We came up from the crypt back into the vast former cathedral. We admired frescoes of the life of Joan of Arc and paintings that commemorated the Catholicization of France. All of a sudden we noticed performers were beginning a show on a paper lined section of the cathedral floor. A man played a violin, another man danced, all while a woman began to sing in French

”listennnn, listen more often.” She meant to listen more often to the voices of the dead. “The dead who have never really left,” as she sang. “The dead who are with us in the flow of the water.” At the end, in a flurry of dancing and singing, the performers brought audience members onto the paper-lined floor to draw. Another communion. Another way of reaching out.

As Catholics, we too must listen more often to the dead. The dead who have never really left. The dead who like us, hope and look to the resurrection to come. Even in secularized, national spaces, these voices are never really silenced.