In this series I’ve been arguing that there are features of daily life which remind us our human identity is not just a socially constructed identity or one reducible to the sum of our biological parts. Instead, our identity is grounded in a metaphysical fact and our stories constructed within certain universal parameters. The goal or aim of any well-intended story is to convey truth– not “my truth” or “your truth” but the truth about “my experience” or “your experience.”

Subsequently, any good story shows how those experiences fit into the whole of human experience. The truth about human identity itself is that we are all made in the image of our Creator. This identity is fundamentally sacred, then biological and social. Identity being sacred fits each and every human being into the whole, something that biological identity and social identity alone cannot do.

Not every story, therefore, is one told by the powerful to keep the marginalized at bay, an assumption C.S. Lewis memorably called “Bulverism.” There is a genuine curiosity about the world that drives the process of deconstruction, and we do discover from time to time things that really are “out there.” Moreover, some of those things we discover are not about the external world but about our own selves living in the world. They are features of our God-given identity that bind us all together, crossing any boundaries of time or culture.

In the last post I told a story of how fear and the overcoming of fear is a common characteristic of all people, everywhere. The triumph over the unknown, be it a personal or a societal unknown, is a pervasive theme in every culture. It is an intimate truth that each and every one of us experience daily. Overcoming fear is but one of these shared features of our common human nature. Another such feature, equally as troubling to us, is the crushing burden of guilt we feel when we do wrong.

The Angry Man in the Car

Years ago, a 30-something male lived in a certain part of the city of Chicago, not too far from downtown. This biological male, who happened to be white and upper-middle class, lived in a neighborhood apartment and drove to work every morning, leaving around 6:30am. He worked in the restaurant business, for the most part. In his spare time he had learned how to dance, competing at local competitions. He was a gym rat who also trained in martial arts. His body was athletic, well-trained, quick and fairly powerful.

This same man also worked in the inner city with school children. He taught dance to 4th and 5th graders who were all black-skinned and lower-middle class, if not under the poverty line. He loved being with these school children and they loved having him teach their class. The young boys especially liked him because he was one of the few male teachers, perhaps one of the few males in general, they interacted with on a daily basis. He would sometimes do push-up competitions with them, which got them super motivated. He got along with the other teachers in the school and especially with the principal, a lovely woman infatuated with the idea of visiting Egypt and seeing the pyramids.

Most acquaintances of this man considered him a good person. He was likeable and had many friends from a wide variety of backgrounds: his friends were gay and straight, white, black, Asian and Hispanic. He was vaguely religious but not too explicit about any aspect of it. He was charitable and impressed many with his willingness to donate time and money. Otherwise there was nothing terribly remarkable about this man.

However, this man had developed a habit of judging people while driving. He would get visibly upset if he saw other drivers breaking the traffic laws, cutting people off in traffic, failing to close the gap at left-turn lanes or driving on the shoulder to pass up slow moving traffic. Over time, his judgements about other people’s bad driving became harsher and harsher, to the point where he began exiting his vehicle to verbally chastise those he thought were being selfish on the road. He felt very self-righteous in doing this, considering himself a protector of society and its norms.

One morning he drove up to the four-way intersection in front of his apartment. A gold SUV approached the intersection from the North heading South. The man was traveling westward and had clearly stopped at the stop sign first. He obviously had the right-of-way to proceed out into the intersection. But, the gold SUV, not paying attention, shot out into the intersection and the front driver side of the SUV came within inches of the front passenger side of the man’s car. Furious at such incompetence, the man, as was now his habit, exited his vehicle, prepared to teach the driver of the SUV a lesson in good driving.

But, this is not a story about anger or irrational action, themselves features common to us all. It is what that self-righteous anger lead to that I am interested in. For in previous encounters this man had always approached drivers who happened to be biologically male, middle-aged and at least commensurate in apparent size and strength. This time, however, that was not the case.

As the man approached the gold SUV in the middle of the intersection, face red with moralizing anger, fists clenched and already hurling condemnations about such irresponsible driving, the first thing he noticed was the child car seat in the middle row of the SUV. Then he saw the terrified face of the mother driving the car, frozen at the sight of this ogre coming at her with veins popping in his forehead. What must have been shooting through this poor mother’s mind, this mother who was taking her son to preschool? The fear in her eyes was vivid. After all, there she was, there was her little child and there was the angry man coming at her.

Did the child begin to cry at the sight of the angry man in the car?

I don’t recall. But what I do recall, being that angry man, is recoiling at my own self; realizing in stark fashion that I was the monster in this scene. But how could this be? How could I, a good person in the eyes of so many, especially my own, terrify a young mother– a mother who had simply been distracted by her little child fidgeting in his car seat? In that moment, like Adam, my eyes were opened to my own guilt and my own shame. Indeed, I was a transgressor, a breaker of a moral law I knew was real but had chosen to ignore so many times prior this one.

I walked back to my car, head hung very low, crushed by the wickedness of my own heart. Guilt weighed upon me, heavy like a millstone.

The Moral Law Within

Immanuel Kant, the great rationalist of the Enlightenment, summed up his reasons for believing in God in his Critique of Practical Reason, saying:

Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and steadily we reflect upon them: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me. I do not seek or conjecture either of them as if they were veiled obscurities or extravagances beyond the horizon of my vision; I see them before me and connect them immediately with the consciousness of my existence.

Kant’s wonder at the cosmos above and the moral law within lead his otherwise skeptical mind to postulate God as a necessary Being. Without God there could be no legitimate reasoning about morality. Kant knew God was required for us to rationally ground moral values and ethical obligations, even if he thought this same God could not be demonstrated through rational proofs. Regarding rational thought about moral values he argues:

Accordingly, the existence of a cause of all nature, distinct from nature itself, and containing the principle of this connexion, namely, of the exact harmony of happiness with morality, is also postulated….This supreme cause must contain the principle of harmony of nature…

Immanuel Kant, Critique of Practical Reason [emphasis added]

God, being the cause of all nature, must also be the cause of the nature of morality, or “the exact harmony of happiness with morality,” and “the principle of harmony of nature.”

That principle of the harmony of nature that is contained in nature’s Creator is the summum bonum of all practical (or prudential) reasoning. The total harmony of nature is the desideratum of all moral thought. This total harmony of all created things is what we all intuitively know as “good,” and when we find ourselves operating to promote that harmony we call this “right.” When we realize we have worked against that harmony, we correctly experience it as “wrong.” Kant would go on to say that our consciousness of this harmony, this summum bonum, and our desire to see it realized is what constitutes moral duty.

The ancient Hebrew word “shalom” captures the same idea of the perfect ordering of creation. Such an ordering, should it ever be realized, would culminate in genuine and lasting peace for man, in final rest for his immortal soul. Both Israel’s prophets and sages longed for this shalom in different ways. The prophets expressed the longing for shalom in emphatic condemnation of the injustices (the disharmony) that engulfed their own immediate society. Alternatively, the wisdom writers spoke of it in timeless reflection on mankind’s foolish and wicked ways (my thanks to Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon for pointing out this biblical pattern to me). The greatest disorder, of course, being the disordered relationship of man to His Creator. This is the source of all other disorders, the wellspring of all other injustices.

Breaking The Law of Harmony

We know when we have transgressed the harmony of God’s world. The indicator of this transgression is our shared experience of guilt. What we do not always know nor always share in common (either at the individual or cultural level) is what that harmony is supposed to be like and how we can properly participate in it. We only experience the guilt of breaking it– the guilt is what we have in common. We argue over the rest, lost without a revelation from the Cause of that Harmony to tell us about what shalom is or what our role in it should be.

Still, that guilt and the accompanying experience of shame over doing wrong is common to us all is uncontroversial. As St. Paul tells us in his letter to the Romans, referencing earlier sages of the biblical revelation,

There is no one righteous,

not even one;

there is no one who seeks God.

All have turned away,

together they have become useless;

there is no one who does good,

there is not even one.Romans 3:10-12 (Psalm 14:1-3, 53:1-3)

But, one need not draw from a revealed source to know that guilt is universal. The mundane reality of guilt and shame is proven every day in our own society. So much so that both are played upon by workers of evil with political agendas who exploit it for their own ends.

Universal Feature #2: The Crushing Burden of Guilt

Guilt and shame are so central to our human identity that those with evil in their hearts know full well that to motivate an individual or population to action, one need not bother with rational calculation or logical argumentation. The deep weight of guilt and shame are sufficient to get people to do what you want them to do. As such, we rarely engender action using the language of numbers or statistics. Instead our calls to arms are always motivated by appeals to virtues and presumed vices, to moral values and the obligations they set upon us.

Master activists like Saul Alinsky understood the universal experience of guilt quite well. In his manual on radical politicism, he offers tactical rules aimed at pressing on the human person where he or she is most sensitive:

The fourth rule is: Make the enemy live up to their own book of rules. You can kill them with this, for they can no more obey their own rules than the Christian church can live up to Christianity.

The fourth rule carries within it the fifth rule: Ridicule is man’s most potent weapon. It is almost impossible to counterattack ridicule. Also it infuriates the opposition, who then react to your advantage.

Saul Alinksy, Rules for Radicals, 128.

Alinsky, no friend of God, nevertheless understood well His creatures are all transgressors, or at least, that we experience ourselves as such. There must truly be a special place in hell for those who use other’s feelings of guilt and shame for their own benefit and their own lust for power. One reason we know to trust the prophetic voices of Scripture, is because they were all persecuted for pointing out the guilt and shame of the people. The true prophet never thrives in the culture he prophesies against, he always is met with suffering. Jesus knew this well when he said that no prophet is welcome in his own town (Luke 4:24).

In the end, however, it is the crushing burden of guilt that either plunges us to insanity, motivates us to evil doing or, God willing, drives us into the arms of the Savior.

Free at Last?

While guilt can motivate us, either to good and harmonious action, as well as to cruel and chaotic acts, we all long to ultimately be set free from guilt. No one hopes to languish in their guilt forever. No one yearns to relish eternally in their shame. This doesn’t even need to be argued.

When I transgressed the harmony of God’s world at the intersection of Southport and Webster so many years ago, I felt the wrongness of that transgression. The wrongness lie in the breaking of shalom, specifically in the form of the stronger (physically speaking) of two sacred image bearers threatening the weaker. It is a dynamic that plays out everywhere and that takes on a wide variety of forms. It is not limited to any one social group or pairing of groups (black, white, male or female, gay or straight) and it is not dependent on biology either. Anyone can break shalom and everyone at some point does.

That incident opened my eyes to one more truth that binds us all: the need to be forgiven for our transgressions. The need to have guilt lifted from our hearts and minds, for every one of us has to some degree found ourselves guilty of breaking the harmony of God. But, to what or to whom do we turn for this deliverance? Perhaps it would have sufficed to simply ask forgiveness of that particular woman on that particular day. Or, since I did not do it then, perhaps it would suffice to track her and her son down and ask for it these 15 some odd years later.

But, not only is the latter essentially impossible, is it not the case that on that day I did something far worse than just sin against this particular woman? Did I not transgress against the full order and harmony of God’s world? After all, isn’t every human person like an entire cosmos unto themselves, a mysterious being full of imaginations, ideas, hopes, dreams and desires? Did I not transgress against the divine image itself, the image of the Creator, the image that made that particular person far more than just her gendered or racialized identity or her biological sex?

But how is one to be forgiven of a transgression against a sacred identity? How is one to be delivered from the guilt of attacking the very image of the Divine?

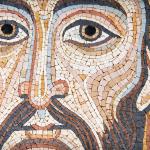

Photo: National Gallery of Slovenia, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons