Over the last week politicians and pundits across the globe, some religious some not, have offered their “thoughts and prayers” for the Ukraine. President Biden opened his statement on the unprovoked Russian invasion saying:

The prayers of the entire world are with the people of Ukraine tonight as they suffer an unprovoked and unjustified attack by Russian military forces.

In the English-speaking world, offering up thoughts and prayers in the wake of a public tragedy has become a type of political ritual. However, the phrase “thoughts and prayers” is ambiguous. When invoked, it leaves it to the hearers as to what kinds of thoughts they should be having toward the victims or what they should think about the conditions that lead to the tragedy being endured.

The assumption seems to be that the thoughts thought will be ones of compassion and empathy for the victims and those closest to them. Perhaps having such thoughts, one might further assume, will remind us of the things that really matter in our own lives. Perhaps having such thoughts might even motivate us to action. After all, one usually has to think before one acts– even if often it seems like we do not.

With regard to lifting up “prayers,” this too is ambiguous. It leaves it up to the hearer to interpret to whom or to what those prayers should be directed. Further, the contents of the prayers are unspecified. One could offer prayers and invocations to the God of the Bible, to Mary the mother of Jesus, to Krishna, to Allah or even to the Satan of the Bible. They could be prayers asking God or Allah to punish evildoers, for Mary to mitigate the emotional pain of the victims or, I suppose, for the Satan to reward those perceived as evildoers and increase the suffering of those perceived as victims. Again, the term “prayers” and the intent behind it are vague and ambiguous.

Therefore, given the wide variety of god-concepts (or real “gods” that modern man only assumes are unreal) which exist in a pluralistic, globalized society, the contents of thoughts and aim of prayers in the wake of human destruction could vary quite drastically. Because of this, it is worth examining the invocation of “thoughts and prayers” more closely.

Skepticism About “Thoughts and Prayers”

The ambiguity of the phrase “thoughts and prayers” often leads many, especially atheists who, in a sense, can only do the thinking part, to become suspicious and even cynical about this seemingly trite phrase. One often finds them reacting angrily on social media to the invocation of “thoughts and prayers,” seeing the phrase as a copout for not engaging in some moral action deemed necessary. For these skeptics, “thoughts and prayers” act as a pale substitute for trying to remedy the concrete conditions that lead to the tragedy or to getting one’s hands dirty in the aftermath of a tragedy.

Whether or not these skeptics are correct in their assessment is not the point of this article, although one does wonder how well “thoughts and prayers” deniers do in living up to their own call for action. Moreover, one could point out that their critique is only partially legitimate. After all, clearly one can invoke the need for thoughts and prayers, do the actual thinking and praying and subsequently engage in the concrete work of responding to tragedy. In fact, thinking and praying prior to acting may lead to a more effective, and more prudent, response. It is at least worth considering that thoughts and prayers may act as a deterrent to impetuous action. Nevertheless, one resonates with “thoughts and prayers” skeptics when one sees its invocation used as a mere platitude–platitudes being by definition banal.

The Scandal of Christian Prayer

Given all of this, however, Christians should have a clear conception of what it means to think about pain and suffering and how to pray for those in the midst of it. After all, in America at least, it does seem that “thoughts and prayers,” when invoked, are more or less aimed at the God of the Bible–or, minimally, to some kind of theistic creator God (the old, liberal “Fatherhood of God, brotherhood of man” type of god).

Christians especially, therefore, should be able to fill in the otherwise empty phrase with some real content. The thinking part should engage the Christian mind, focusing it on the theological and moral ramifications of the tragedy and what one could possibly do about it. The prayer part should have some sense of what to pray for and, most certainly, Whom to call upon in prayer.

Regarding prayer, however, there are a few things that Christians should be praying for that are likely quite counterintuitive to what most non-Christians think of when our politicians and celebrities call for “thoughts and prayers.” Some of these prayers may be in fact so counterintuitive to the popular conception of “thoughts and prayers” that they will be considered outright scandalous. But so be it, let the scandalous abound if that is what the circumstances require. Scandalous prayers, or prayers perceived as such, may be exactly what we need. Popular opinion or convention should not be the determining factor in what we pray for or about.

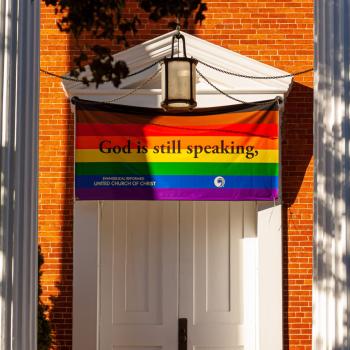

Safe prayers, therefore, are far more likely to be prayers shaped by a certain cultural norm than by the Bible with its “antiquated” notions about human nature and history. In contrast to culturally safe prayers, prayers shaped in accordance with biblical truths should rouse in us something which forces us to question our cultural and moral assumptions. Today the Church needs more scandalous prayers and far less safe ones, and not just in its reflections on war.

As I have argued before, a Church that does not subvert the cultural instinct that arises so naturally within us, is a Church not worth dedicating our lives to. Prayers that are mere echoes of cultural moods or expressions of its norms can hardly be prayers of great import or power. Even prayers offered to the one true God can be so grotesquely distorted by cultural sentiment that one could only hope they not only go unanswered by Yahweh, but that the one invoking God’s name have their incantation turned back against them.

Subversion and The Status Quo

This is not to say that everything in culture is antagonistic to the Christian ethic or that the Christian ethic is antagonistic to everything in the culture. It is just to say that the cultural norm and the Christian norm are never one and the same. Because of this, the true Church is always a reforming agent in the culture, even while acting as a protector of the status quo at the same time.

Alasdair MacIntyre, in his 1968 treatise on Marxism and Christianity, points out this necessary tension between religion and culture:

The great historical religions, as some Marxist writers have seen, have been rich enough both to express and to sanction the existing social structure and to provide a vision of an alternative, even if it was an alternative that could not be realized within the present world….

But religion is only able to have this latter transforming function because and insofar as it enables individuals to identify and to understand themselves independently of their position in the existing social structure. It is in the contrast between what society tells a man he is and what religion tells him he is that he is able to find grounds both for criticizing the status quo and for believing that it is possible for him to act with others in changing it.

Alasdair MacIntyre. “Marxism and Christianity.” Apple Books.

Part of Christianity is Christian prayer. Indeed it is a necessary part. For Christian prayer to lead to the transformation of the culture, and those within it, it must act subversively in relation to the culture’s understanding of prayer. As the Church’s theology must tell man what he is and what is his purpose more so than the culture does (or can), so too must Christian prayer address that deeper identity and purpose. If it does not address man’s true nature and his actual purpose, then it is a prayer of the culture in which the Church resides and not a prayer of the Church, the mystical body of Christ that transcends all culture.

Good, But Insufficient Prayers

Most people would want Ukrainians to escape the current horror of the Russian invasion. They would want Russia to put down its guns and for Ukranian citizens to be able to go back to life as normal. They would pray that no one else would die or be gravely injured. They would pray that the ordinary rhythm of life would be restored and that some degree of peace and modicum of prosperity could be salvaged in the wake of a cruel and gratuitous aggression. They would pray that families would be reunited, children spared, schools reopened, businesses restarted and social life resumed.

Further, if they were honest, they might also pray for the punishment of the guilty parties. Perhaps they would want to see Vladimir Putin on trial (and they would be right to want that), or maybe even hanged from the highest gallows (debatable, but at least understandable). No one would be wrong to pray for all these things–the alleviation of pain and punishment of wrongdoing. Roughly these sentiments seem to be the assumed contents of “thoughts and prayers” when invoked by the leaders of our western democratic nations–those nations that retain the affective aspect of Christian morality, even if they ignore the moral content of the Bible.

For biblical Christians, however, these things in themselves are superficial. None of the things thought about or prayed for by most of us when “thoughts and prayers” are invoked by our leaders are of ultimate value on a biblical worldview. Longevity of life, physical health, able-bodiedness, material prosperity and even social harmony and emotional peace are of no ultimate value if separated from the spiritual realties that underlie them all. Yet we fail to see this, even in the Church.

But why is this the case?

Calculating Horrors: The Problem With Our Utilitarian Prayers

One problem is that we live in a culture so imbued with a consequentialist idea of ethics that even the culture’s churches can no longer recognize anything other than a pleasure versus pain calculus as the standard for moral goodness or moral badness. Pain in this culture is an intrinsic evil. Pleasure, its opposite, an intrinsic good. Worked out in actions, these utilitarian values are considered the standard by which an act is deemed to be moral or not. If the consequences of an action increase the degree or quality of a pleasure, it is morally good. If it increases the degree or intensity of a pain, it is morally bad.

However, long before films like The Matrix or Total Recall (the 1990 version), even secular novelists like Aldous Huxley and philosophers like Robert Nozick imagined dystopian futures or dystopian states, where all of the material, social and emotional goods of consequentialism were guaranteed. Yet the conclusions of Huxley’s Brave New World or Nozick’s “The Experience Machine,” have been considered far more unsettling than appealing–and for good reason.

The idea of mapping out our moral and existential lives onto some pleasure versus pain matrix and finding some means to engineer that reality becomes incredibly distasteful, even horrifying, to us rather quickly. As Nozick points out in a longer 1989 version of “The Experience Machine,” what we all really want is not just pleasure or a maximizing of it, what we want is a deep connection to reality, even a reality that can hurt:

We care about more than just how things feel to us from the inside; there is more to life than feeling happy. We care about what is actually the case. We want certain situations we value, prize, and think important to actually hold and be so. We want our beliefs, or certain of them, to be true and accurate; we want our emotions, or certain important ones, to be based upon facts that hold and to be fitting. We want to be importantly connected to reality, not to live in a delusion.

Robert Nozick, The Examined Life [emphasis added]

In some very real way, we all know it is better for Ukrainians and Russians to be fighting right now in a gruesome and unjust war, than for all Russians and Ukrainians to be hooked up to some “pleasure machine” or living in a totally euphoric, yet drug-induced, state. Right now, perhaps more than ever, Ukrainians and Russian alike (and everyone else in Ukraine) are experiencing aspects of reality, even deeper connections to it, than they otherwise would not have experienced (see my caveat to this below), and that many of us sitting in “safe” confines are actually longing for.

This too must be taken into account when Christians offer up their thoughts and prayers. For while we certainly can and do pray for the alleviation of pain and the mitigation of violence, we must also take into account how that pain may be transforming people’s lives right now. It may not always be for the worse from a spiritual perspective. Our prayers cannot be offered up from within a consequentialist framework that takes pleasure and pain into account, but nothing else.

Prayers And The Eternal Frame

Even the condemnation or sentencing of the cruel and unusual by a human court are of no ultimate consequence if there is no ultimate justice– the measure of human justice never equaling the tremendous nature of man’s cruelty to man. We know that only an eternal and transcendent context could ever justify the horror of a Ukrainian invasion, a Rwandan genocide, or of some particularly mundane malevolence like this one. The depth and power of evil simply cannot be deeper than that of goodness.

But this is not just a statement of sentimentalism or wishful thinking. We all recognize that real evil and genuine goodness have a quality to them that make their existence highly implausible on an atheistic, materialistic worldview. Clearly the horrors of the Holocaust are not reducible to mere molecules in motions, just as their counterparts in virtue are not exhausted by an analysis of atomic structures driven by random natural forces. The phenomena of evil and supererogatory acts provide strong evidence for the transcendent and the eternal.

None of this is to say that it isn’t good to pray for physical safety or end to apparent unnecessary pain or suffering. It only means that these prayers mean little if we fail to acknowledge the spiritual war that underlies the physical manifestations of violence and aggression. The reality of human existence ultimately is this: our physical well-being is downstream from our spiritual well-being. Our current bodies, while important, are only as good as the souls that are embodied by them. It is not just that morality transcends time and place, it is that every human person does as well.

Thus, if our souls are not healthy, then the health of the body is not only negligible but potentially a source of the very evil from which we seek to escape. Our cultural morality, a very superficial form of consequentialism, unfortunately prevents many Christians from seeing this very thing. And so we often pray only for people to physically escape danger, to not get killed or maimed and to otherwise be protected from harm. While these are not bad prayers, they really are just superficial ones. They are superficial because they only take into account two things: physical well being and emotional happiness. What they fail to account for, or at least fail to address, is virtue and depth of purpose–two things war has been known to produce.

Two “Scandalous” Prayers Christians Should Pray

Given this analysis, this unpopular ontology that leads to an even more scandalous teleology, there are at least two types of prayers that Christians should pray when our leaders invoke the need for “thoughts and prayers.” The first of these prayers is one Christians must pray right now and continuously for those in Ukraine, and it is this: that those who know Christ may die well, and that their death may act as a testimony to Christ’s love and our confidence in His gift of eternal life.

In other words, we should not just pray that those who already know Christ escape danger. In fact, perhaps we should not pray that at all– their deaths in this war and at this time possibly being the actual culmination of their Christian mission. This would be especially the case if we believe that Christians can indeed lose their faith, for which there is good biblical evidence (see Hebrews 6). An untimely death in the eyes of men may in fact be the ultimate grace in God’s eyes. If so, then it is not an untimely death but a death that comes in perfect time.

The second “scandalous” prayer that Christians should pray is simply the corollary to this one– that those who do not know Christ, especially those who clearly do not know Him (like Putin himself or the Russian commanders and foot soldiers conducting the atrocity) might actually survive the conflict. After all, God’s glory is most revealed when one sinner repents and is transformed through the power of God in Christ.

This is the one, ultimate good– a good that transcends all human iniquity, all evil and suffering. It is a good that no pleasure versus pain matrix can measure, for it is the total transformation of the human being into a new creature. When the image of God is restored in man, it is reality remade. It is also something that cannot be undone by anything physical, like a bomb, a bullet or grenade. As Christians, have we forgotten it is exactly this that the very angels of God rejoice at witnessing (Luke 15:10)? So yes, we must pray for our enemies, especially for them.

C.S. Lewis articulated many of these ideas in his famous treatise on spiritual warfare, The Screwtape Letters, written as German bombs were devastating London like Russian artillery is devastating Kiev today. As Wormwood wrestles with his elder uncle, Screwtape, over the soul of one, ordinary Christian, Screwtape makes it clear that war itself can be the one of the best instruments for the Enemy (that’s God to Screwtape) to rouse man out of his spiritual malaise– to connect him to the deeper things of reality.

Further, if the sole aim of the devil is to truly take a man’s soul (which it is), then death itself, regardless of its cause, can work either to his advantage or his disadvantage. For the devil, the death of a true follower of Christ is itself the ultimate defeat of Satan:

At the present moment, as the full impact of the war draws nearer and his worldly hopes take a proportionately lower place in his mind, full of his defence work, full of the girl, forced to attend to his neighbours more than he has ever done before and liking it more than he expected, ‘taken out of himself’ as the humans say, and daily increasing in conscious dependence on the Enemy, he will almost certainly be lost to us if he is killed tonight.

C. S. Lewis. “The Screwtape Letters.” Apple Books.

Lewis, himself a veteran of WWI, knew that to die tonight may well be yet another victory for Christ and a further loss for the enemies of God. I myself have experienced the same, especially on one particularly dicey day in a relatively unknown part of eastern Afghanistan.

A Caveat to The Ukrainian Experience

I should caveat this entire essay however by pointing out that Ukrainians are not necessarily a decadent and coddled people like we Americans. Eastern Christians have dealt with tragedies like these for generations. They are harder and more resilient than we, at least on average. They are not strangers to real adversity. Most of them would probably laugh at our “cancel culture,” its obsession with mirco-aggressions and its conflation of bruised egos with bruised ribs.

A close friend who has taught seminary classes in Kiev told me about a conversation he had with one of his Ukranian counterparts the day after the invasion. In that conversation the Ukrainian professor perfectly summed up life in Ukraine compared to life in the United States saying: “we were just getting to the point where we could complain about the barbecue not working…and now this.”

If Christianity is true, which it is, then it is hard to know who is in greater danger right now, the Ukrainian running to and fro looking for shelter from Russian artillery or the average American complaining about his broken Weber grill.

Let us pray.