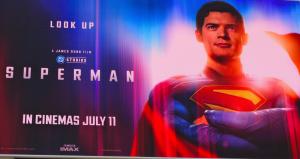

I did not want to write this movie review. I had better things to do, at least, I thought I did, than to address one of the worst movies I have seen in a long time. That movie is James Gunn’s reboot of the Superman mythology, simply titled Superman. Instead, I could have made progress on my book on Neopaganism, or read more of D.A. Carson’s commentary on John’s Gospel or started Book 1 of Tertullian’s “5 Books Against Marcion.” I could even have continued in Diarmaid MacCulloch’s Christianity, The First Three Thousand Years, (a book worthy of both reading and criticizing). Then there are the journal articles to prepare and podcasts to record, like this one.

Still I felt compelled to do something about this film. Especially in light of the fact that many people I respect, both as Christians and Christian thinkers, have astonishingly praised this latest entry into the Superman lore.

And so, here it goes.

First, I will critique the aesthetics of the film, which alone should downgrade its praiseworthiness. Then I will discuss how theologically this movie is not only a hot mess, but argue its storyline comes close to inverting the message of the Gospel itself. This, by the way, puts it at odds with the original, and quite good, 1978 Superman (the one with Christopher Reeves and the great Gene Hackman).

Gunn’s Superman and the Aesthetics of an Adolescent Mind

I cannot go back and watch this movie again, especially since I nearly walked out of it (something I rarely ever do). So I am going off memory for this article. Perhaps the first thing to point out, however, is the abject shallowness of Gunn’s whole project. Every character in Gunn’s film falls absolutely flat, nay, just is flat. We find here no nuance, no moral complexity nor any depth of emotion. Each character, the second primary aesthetic feature according to Aristotle (along with plot), is completely predictable, absolutely basic and artistically cheap. Let’s look at the three main characters: Lex Luthor, Lois Lane and Superman himself.

Lex Luthor

Lex Luthor (Nicholas Hoult) is only a raving madman. He is malicious to the core and always to the maximum degree–in every scene. Yet his intense hatred of Superman is never adequately explained. This is in spite of the fact it is made totally obvious and shown as all-encompassing. There is no subtly to the character whatsoever. He is always on the brink of rage, his malevolence and greed are clear for all to see and his role as antagonist is never offset with even a modicum of humor or an iota of humanity. It is as simplistic a portrayal of evil as one can find and, as such, a very boring one.

Hoult’s Luthor is, in this sense, quite unlike Hackman’s original. Hackman’s Luthor is not only winsome, but is the type of bad guy one inevitably finds oneself rooting for, precisely because he is so clever, genuinely funny, and temptingly human (consider the whole schtick with the toupee, for example). This makes Donner’s Luthor a much more sophisticated fiend and a far more engaging character. Of Hoult’s Luthor, there is nothing winsome about him nor anything particularly clever and certainly nothing humorous. One wonders why he has any partners in crime at all, especially since those partnering with him seem utterly normal and decent (with the exception of the eccentric leader of Boravia, an almost pointless character in the film).

Moreover, as is now typical in these movies, technology and technological mastery replace human ingenuity and the more subtle, psychological trickery of the old-school criminal mastermind. Hoult’s Luther is merely a tech guru, with little to no actual personality to draw in the audience: like “Rain Man” but with the capacity for one emotion: rage. Gunn is naive in his portrayal of the arch-antagonist. His tactic is basically to shout at us throughout the film: “hey, hey everyone, here is the guy you are supposed to hate! Hey, yeah, this guy, he’s the bad guy, just so you know!”

Yes, yes, we get it.

Lois Lane

The same goes for Lois Lane (Rachel Brosnahan), an uninspiring, insipid and trendy single gal who sort of loves Clark/Superman, but, you know, her relationships “never quite work out.” Of course, as is the norm, this implies Lois has had many prior relationships before Clark, which, obviously, we are supposed to overlook in favor of her other virtues (whatever those might be). And so she wavers in her affections for Clark in typical, noncommittal, Seinfeldian fashion. Although even the dialogue about her difficulties with relationships is unoriginal and boring. When Clark storms out of her apartment in one scene, the audience is left wondering why. What was the big deal anyway?

Gunn’s Lois is very different from Sam Raimi’s “MJ” in his two Spiderman entries (2002 and 2004), played excellently by Kirsten Dunst. Raimi’s MJ, unlike Gunn’s Lois, is a complex character. She shows a genuine enthrallment with Spiderman, a real concern for his well-being, and a confusion about where she stands with regard to both his nature and his mission. Instead, with Lois, Superman comes off as just another guy, one who she may or may not like or decide to stay with. But what will determine that are the same kinds of things that determine any of our relationships: can they communicate well, is there chemistry in the bedroom, will her career choices get in the way, etc, etc.

But these kinds of things aren’t even deep or meaningful things in our own, real-life relationships; they are themselves superficial things. , not like Lois is wondering whether or not she can have children with this Superman, or vice-versa. Thus, right off the bat when we see Clark and Lois alone for the first time, we get the immediate, and hackneyed, hot and heavy making out to show that they are at least sexually compatible. But this is followed, predictably, by a poorly contrived conflict that engenders an inauthentic “breaking up” and a brief, albeit unconvincing, rift in their relationship. It’s just all so, well, you know, teenage angsty. To be blunt, it is Friends all over again.

Yet this angst carries out between two adults who are supposed to have had all kinds of profound experiences. The kind that most of us, either in the real world or in the Marvel or DC universes, could only dream of; like stopping international wars, battling cosmic forces and dealing with evil and suffering of a tremendous degree and variety. In addition, we know Lois and Clark will get back together. There is never any doubt about it. Gunn’s film never generates any serious concern that the relationship will go sour or fail, as Raimi does in his films. In fact, Gunn’s film generates no serious concern about anything. And that is kind of the problem, isn’t it?

And so with Lois we get the same thing we have seen in almost every superhero movie going back to the original Ironman, which is now pushing 20 years: the trendy, sassy, shallow postmodern girl. Lacking in any real charm or any genuine virtue but, well, sassy. And when it comes to character, sass suffices in Gunn’s artistic oeuvre. As such, the dialogue between Clark and Lois, and between all the characters really, is one extended series of sarcastic quips, rude or lewd snark, or, in the case of Superman, superficial pontifications of “do-goodery.” Only occasionally is this litany of inane dialogue broken up by stock-in-trade sentimentalism, like when Clark’s earthly father, a character we will return to in part two of this review, tells Clark that he will love him no matter what…yada, yada, yada..because that is what parents do…yada, yada, yada.

Superman/Clark Kent

Then there is Superman himself. It’s not that David Corenswet is a bad actor. It is just as is so often the case, there is no good script for the actor to work with, let alone direction. The persistent need for contemporary writers and directors to always aim for the lowest common denominator with regards to emotional and linguistic intelligence (the two being intimately related), so that every superhero movie, with rare exception, has the verbal sophistication and depth of feeling as the stereotypical high school locker room, is mind boggling. Yet people continue to accept this level of, what any good Brit might call “drivel,” and treat it as conducive to the creation of high drama. And, it should be noted, high drama is not impossible to attain within the realm of the superhero genre; the proof of which is, again, Donner’s 1978 original and Raimi’s Spidermen, especially Spiderman 2 (2004).

Compare, for example, the final scene in Donner’s film, where Reeves brilliantly portrays Superman’s genuine agony over Lois’ death and how that agony drives him to break with the moral imperative of his “divine” parents, Jor-el and Lara. There is no scene anywhere in Gunn’s offering that comes close, or that even attempts to come close, to the pathos which Donner’s film actually achieves. Pathos, or the cathartic experience it generates, was, last time I checked, still the primary aim of any good work of tragedy (And yes, on Aristotle’s definition, Superman would count as a tragedy and not a comedy, in spite of all the lame jokes).

In the second part of this review, I will address Clark/Superman in greater detail when I analyze the theological implications of the human Clark rebelling against his own nature as the (semi)divine Superman. The main problem surrounding Gunn’s Superman is not so much the lack of development of his character, the poorly written dialogue put in his mouth, or the lack of nuanced thought. Rather it is the inversion of the character’s nature and mission. But, again, I’ll leave that for part two.

Finally, one might point out that on the characterization of Clark Kent. If Clark’s persona is meant to contrast with that of his omnipotent alias, how this is done in Gunn’s film is unclear. In Reeve’s Clark we got a bumbling, fumbling, socially awkward “nerd.” The glasses being the symbol of Clark’s persona as the physically graceless, social weirdo who doesn’t fit in to either his own body or his society. At the time, the disguise fit the cultural context, the “nerd” being the cultural pariah and exemplar of weakness: both physical weakness and social ineptitude.

However, the concept of the “nerd” has changed since Donner’s 1978 film. Nerd-dom is no longer seen as socially awkward, and it has found a certain pride-of-place in the culture. Successful nerds, especially in the realm of tech, like Bill Gates or, more recently, Peter Thiel, have made the image of “the geek” cool. And so one would think Gunn might have to come up with some other social feature to contrast Clark with the all-powerful Superman. What could be the feature that shows Clark’s humility or demonstrates his outlier status from the surrounding culture? Of course, this would demand actual creativity.

Gunn’s answer is to suggest it is Clark’s moral compass, his ability to see everyone as beautiful, that makes him different. This is, according to Clark, the “real punk rock.” The only problem with this is it doesn’t really come off as something that makes Clark socially awkward or unusual, nor that contrasts with his omnipotence as Superman. It is not a characteristic that makes Clark unacceptable to the culture. It’s the standard orientation and attitude of Lois, Clark’s parents, and most of the other characters around Clark, all of whom embrace a basic “Love is Love” ethic.

Nor does Clark’s goodness contrast with his superhuman power. And so Clark is not really different from Superman in any significant way. It is only the pair of glasses, which, as is alluded to in the film, have some special technical power to mask his true identity, that make Clark distinct from Superman. The distinction is, however, one without a difference. And so on a technical note, Corenswet doesn’t have to portray Clark as in any way different or distinct from Superman, as Reeves had to do and did.

Gunn’s Superman Gaffe: Confusing Plot and Character with Spectacle

Beyond the individual characters and their unoriginal and uninspiring dialogue (with possibly one exception, Edi Gatheji’s “Mr Terrific”) is the incoherent mess of non-stop visual stunts and cacophony of special effects; all of which is now standard formula for any action film, especially of the superhero genre. Speaking of Aristotle, his sixth and least important criteria for drama was “Spectacle.” Spectacle being basically what we would now call special effects. This would include lighting, backdrops, costumes and staging, etc. It might also include what we refer to today as cinematography, the overall coordination of a scene’s visual parts.

Yet this is where Gunn, like so many others (Peter Jackson?), continues the awful trend of conflating the two most important criteria of art, Plot and Character, with the least important, Spectacle. They direct as if to say that the Spectacle alone should be sufficient to generate the pathos needed for the cathartic experience. The ridiculous amount of time and energy wasted on spectacular devices, over-the-top visuals and ridiculous costumes overwhelms any attempt at plot or character development, let alone attention to words. And you can forget Aristotle’s category of “Thought” as an artistic possibility for filmmakers like Gunn, who seem incapable of delivering anything of the inner life of a character apart from them simply blurting it out in, again, an adolescent, gamer-inspired idiom. It’s almost as if Gunn, and the writers, have never actually read a book. At least not an old book.

Thus, why bother with plot and character, or diction, when pure visual stimulation will suffice to entertain an audience whose souls have been shaped by little more than the literary world of the comic book itself: an audience stuck in a perpetual childhood and uninterested in moral depth or narratival complexity. This leads me to my final conclusion about the aesthetics of Gunn’s film: it is aesthetics for and by the aesthete.

Kierkegaard’s Aesthete and Our Endless Adolescence

For Kierkegaard, there were three stages of personal development–of becoming a true “self”– in life: the aesthetic, the ethical and the religious. The stages are not necessarily in order, and one can certainly move through all three and retain genuine aspects of each in the journey. However, there is a progress from one to the other, the religious being the highest of the three. The aesthetic stage, alternatively, is the most base of all.

The aesthetic is the stage of human development that begins and ends in stimulation and whose only aim is pleasure: be it physical or emotional or intellectual. The aesthete’s main vice, the thing to be avoided most, is boredom. Her main virtue, the thing to be sought after most, is arbitrariness (or novelty). This is not to say that the objects that the aesthete occupies herself with need be trivial things, like perhaps this movie. The aesthete can be pleased by Superman one day and Casablanca the next. The balance of objectively better and worse itself acting as a kind of aesthetic moderation: a cheap Rosé can sometimes meet the same need as the finest Red.

That said, it is the content of a movie like Gunn’s Superman, and the response to it by so many that tells us something about ourselves. Or, at least, should tell us something. After all, if there is one thing this movie does, and does “well,” it is revel in novelty and advance the arbitrary. One assumes the aim is to ensure the audience doesn’t experience boredom.

And so we are offered a great ensemble of images: random, kaiju-like monsters terrorizing the city, unexplained “pocket universes” replete with inter-dimensional prisons, ion-particle rivers and alien babies, elemental men who can turn into any substance in the universe, fictional warring nations, crazed eastern European dictators, battle bots, ultramen, mutant female baddies with genetically modified blood (or something like that), superdogs, metahumans, inter-dimensional imps, dancing robot medics, and, if that were not enough, thrown in at the end for good measure: a drunken, punk-rock supergirl who frequents intergalactic raves (or something like that).

Truly, to use a term Kierkegaard applied to the aesthete, this is all quite fantastic. While we understand that for the comic book enthusiasts these are all “easter eggs,” i.e. quick references to characters or events from past issues, the effect is one of stimulation and reference solely for the sake of stimulation and reference. None of these easter eggs adds to the present story or its characters. Instead, this panoply of images acts as an infinite loop of pop culture referring back on itself: a perpetual commodification of cultural products, which empties any of them of real meaning: the one thing Marx warned about that he actually got right.

But imagination and fantasy are not always good things, not in themselves at least. Endless fantasizing, the mere propagation of images and characters because we can create them, is not only a fruitless endeavor but a dangerous one. Imagination must be employed to lead us back to truth, both truth about God and ourselves. Fantasy for the sake of the fantastic, however, is, to paraphrase Kierkegaard, something that leads us away from our true selves. My speculation is because it never lands us anywhere. And neither does Superman land anywhere. Instead, it leaves us all hanging or, as in the final scene, floating in some kind of romantic embrace. But it is an embrace we suspect will not end in anything solid, like an actual marriage, or anything truly generative, like children.

For part two of this review, a theological analysis of the film, see here.