In Igbo Jurisprudence: An African Philosophy of Law, Nkuzi Michael Nnam briefly mentions two examples of what one might dare call “white goodness” on the continent of Africa. Interestingly, both occurred not in recent history but in the 19th century–at the height of white supremacy and European colonialism (which are basically the same thing).

I highlight these two facts of history for a few reasons: first, to show that human beings, regardless of racial identity, are all wicked. This means that moral goodness is not tied to, or in anyway grounded in, racial identity. Second, to show that human beings, regardless of racial identity, are capable of transcending their wickedness. This means that regardless of social identity, moral goodness is possible and moral wickedness avoidable.

This is a message worth spreading in America today, especially as battle lines continue to be drawn by those who themselves are either dull of mind or cruel at heart (or perhaps both). I speak about those who want to reserve moral purity for one group while ascribing moral wickedness to another, and who base that decision on certain external features of each group. This is a phenomena common throughout history, but that repeats itself with every generation. Many today refer to it as “tribalism.”

Here are two examples therefore that disrupt tribalist narratives, at least those based on race.

The British Soldiers Who Fought Against Africans to Free Slaves

In his book, Professor Nnam mentions the kind of historical fact that often goes under the radar or, for ideological reasons, is actively suppressed in contemporary American culture:

The slave trade was abolished in the United Kingdom by an Act of Parliament in 1807. Thus the British naval squadron was faced with the task of stamping out the slave trade which was then at its peak on the coast of Africa. Native chiefs and African middle men turned deaf ears to the entire idea of its abolition because they found it lucrative. Britain encouraged legitimate trade [in things other than persons] and managed to oust several Yoruba kings from their thrones for refusing to give up the trade.

Nnam, Igbo Jurisprudence, 26-27

Here is a historical fact that doesn’t sit well with the overriding narrative of today’s Critical Race Theory, for example: white, British (and likely Christian) troops being sent into Africa to dispose of black Africans (either Muslim or folk religious) who refused to give up enslaving and selling other Africans.

Nnam goes on to recount one particular African warlord, clearly Muslim given his name and title, who was particularly resistant to the British abolition of the slave trade:

In the North, Hausa and Fulani Emirs were not easy to deal with either. One of the stories still told about the struggle with native kings to stop slavery centers on Ibrahim Nagwamatse, Emir of Kontagora, who in 1880 started an endless war with other kingdoms to expand his diminutive emirate. The British captured him along with the slaves he had intended to sell to foreign smugglers and asked him to give up the trade. Ibrahim supposedly replied, ‘Can you stop a cat from mousing? I shall die with a slave in my mouth.’

Again the point here is not to excuse the slave trade that was perpetrated for centuries by white(ish) Europeans. But, it is to counter a false narrative that permeates our current “social imaginary” (to borrow Charles Taylor’s useful term). That false narrative is one that, given its Marxist commitments, tries to clearly delineate oppressor versus oppressed group based on external, social features–in this case on race.

Evil Permeates Every Heart

This kind of generalization never works, for, as Solzhenitsyn succinctly put it in The Gulag Archipelago,

The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either – but right through every human heart…even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained. And even in the best of all hearts, there remains…an uprooted small corner of evil.

Nor does the line separating between good and evil pass through racial groups, as much as populist critical race theorist might suggest. The Apostle Paul, referring to multiple passages in the Hebrew bible, lays out for us this universal principle when he says in his letter to the church in Rome:

There is no one righteous,

not even one;

there is no one who understands,

there is no one who seeks God.

All have turned away,

together they have become

useless;

there is no one who does good,

there is not even one.Romans 3:10-12

Paul’s reference to “no one” can, in the narrow sense, mean the nation of Israel, especially in regard to the Mosaic Law. But Paul expands that to mean all people of all nations when he says in verse 9:

What then? Are we [Jews] any better? Not at all! For we have previously charged that both Jews and Gentiles are all under sin, as it is written…

In sum, we might rightly say that Christian Europe was more culpable for slavery than non-Christian black Africa, in the same way the Jews were more responsible than the Greek and Roman Gentiles. However, what clearly cannot be claimed, at least not without devolving into pure obscurantism, is that slavery and the slave trade, or even the modern racial hierarchies that tried to justify slavery, were in any way unique to white Europeans.

The Scottish Lass Who Brought Christ’s Love To The Poor of Africa

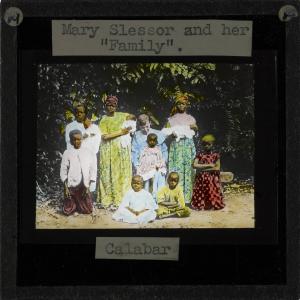

How white would a Scottish lass of the 19th century have been? Not just in skin color, but in culture? Mary Slessor was likely as white as white could be when she set out for the African coast in 1876 to follow in the footsteps of another white missionary, David Livingstone. Slessor, however, was not like today’s liberal, suburban whites in America (“Karens” as the social justice crowd calls them). She grew up poor and very, very tough, living in the slums of Dundee and working 12-hour shifts in a jute factory.

Nnam’s book, which is not a book about missionaries, or even about Christianity, nevertheless has this to say about Slessor’s legacy in Nigeria:

The missionaries soon learned that traditional African religion is inseparable from an entire form of life. To win converts, therefore one has the difficult task of replacing a whole complex of belief and conviction, for in most ethnic societies religion forms a conspicuous part, a system embracing family and social relations, as well as economic and political principles.

A fine example of such a missionary was Mary Slessor, a Scot who never treated the African as a person of inferior quality even though, like other missionaries, she was not blind to the inadequacies of African society. Having arrived in 1876 in the Okoyong Town of Cross River, she began the work that is remembered to this day. The pupils who studied on [sic] her grade school class regarded her as the greatest missionary humanitarian in Nigerian history. She was one of the very few missionaries who are known to have shared their lives with the poor, eating their food and making efforts to speak and understand their language. As a result she was able to penetrate hearts, and so persuaded the people to put an end to the killing of twins.

Is Nnam lying here? Or is he being overly sentimental? Given that the book is entirely about traditional and contemporary Jurisprudence in Nigeria, there is no reason to think that. This testimony about Slessor rings true and fair. It speaks for itself, Slessor was a white saint in black Africa (just as the venerable John Augustus Tolton , a former slave, was a black saint in white America).

Corrupted Culture and the Missionary Endeavor

There is much to unpack in Nnam’s passage about Mary Slessor. First, is his recognition that Christian missionaries did have to contend with the religious culture of the nations they were evangelizing. Missionaries explicitly considered the fact that traditional cultures (not just African, but any traditional culture) were shaped first and foremost by their religious beliefs and practices. Some aspect of a non-Christian culture had to change, albeit certainly not every aspect of it.

Theologians and missionaries have wrestled for centuries over exactly what parts of a culture need to be converted and which can and should remain in tact. A letter written by Pope Gregory the Great in 601 to Mellitus, a monk leading the second great missionary trip to then pagan England, describes this contemplation of the right approach to indigenous cultural forms in missionary work:

When Almighty God has led you to the most reverend Bishop Augustine [not to be confused with St. Augustine of Hippo], tell him what I have long been considering in my own mind concerning the matter of the English people; to wit, that the temples of the idols in that nation ought not to be destroyed; but let the idols that are in them be destroyed; let water be consecrated and sprinkled in said temples, let altars be erected, and relics placed there.

For if these temples are well built, it is requisite that they be converted from the worship of devils to the service of the true God; that the nation, seeing that their temples are not destroyed, may remove error from their hearts and, knowing and adoring the true God, may the more freely resort to the places to which they have been accustomed.

Gregory does go on to say that the Angles and Saxons who populated England at that time had “rude natures,” but it is unclear what he means by this, especially given how warlike those particular tribes actually were. The point being, however, that missionaries took very seriously how to preserve indigenous culture from the very beginning, even the white indigenous culture of the Angle-Saxons! (I’m being intentionally anachronistic here for the sake of irony). Thus, even temple structures once dedicated to demon-gods might be preserved, so long as their function was reappropriated. The native tribes were, after all, accustomed to their form.

An excellent film that depicts this cultural discernment by Christian missionaries is Roland Joffe’s 1986 The Mission, about Jesuit evangelists in South America. This does not of course mean that there were not missionaries who failed to maintain and preserve those aspects of non-Christian cultures which should have been preserved, confusing European culture with Christian faith. But, given what Nnam says here, Slessor was clearly not one of those kinds of missionaries.

The Individual Soul And True Missions

The reason why Slessor was not that kind of missionary, one who conflated European culture with Christianity, was her love of people. Nnam tells us Slessor was a “fine example” of missionary work, because she treated every African as equal or “not inferior,” even though she saw the problems of a culture devoid of Christ. One of those problems was the killing of twins by local tribes, an abominable practice related directly to local religious belief– the kind of cultural form that indeed had to be changed for the sake of Christ.

In her simple seeing of the image of God in all people, Slessor was able to integrate into the local Okoyong culture. Not only that, but she herself, like Francis of Assisi centuries prior, became part of the poor of that culture. In becoming one of the Okoyong for Christ, even Mary Slessor, a white Scot tainted with the same evil as the white slave traders that came before her or her black contemporary on the continent, Emir Ibrahim Nagwamatse, was not only able to transcend her sin nature, but in doing so became a good white person in black Africa. In being a bridgehead for good, she “penetrated hearts,” an act that resulted in ending the unnecessary killing of children.

Conclusion: We Are All Sinners, Saved By Grace

It may sound trite on a blog dedicated explicitly to Evangelical Christian thought to talk about original sin and saving grace. However, it must be restated clearly ever so often and for every generation: we are all sinners regardless of race, creed, sex, economic class or culture. Evil is not exclusive to any particular gender or racial identity, it truly cuts directly through the heart of every individual.

Any answer worthy of consideration to the problem of evil, therefore, has to deal directly with the human heart. It cannot deal merely with social structures or social identity categories. The history of slavery proves that it is wicked human hearts, hearts that themselves are genderless and colorless, that set up the conditions for more complex, and cruel, social structures.

The only sufficient answer, however, to the problem of the human heart is, and always has been, the grace of God to man. And so the problem of original sin, or human unrighteousness, that St. Paul describes in his letter to the Romans, he answers a few passages later:

21 But now God has shown us a way to be made right with him without keeping the requirements of the law, as was promised in the writings of Moses[i] and the prophets long ago. 22 We are made right with God by placing our faith in Jesus Christ. And this is true for everyone who believes, no matter who we are.

23 For everyone has sinned; we all fall short of God’s glorious standard.24 Yet God, in his grace, freely makes us right in his sight. He did this through Christ Jesus when he freed us from the penalty for our sins.25 For God presented Jesus as the sacrifice for sin. People are made right with God when they believe that Jesus sacrificed his life, shedding his blood. This sacrifice shows that God was being fair when he held back and did not punish those who sinned in times past, 26 for he was looking ahead and including them in what he would do in this present time. God did this to demonstrate his righteousness, for he himself is fair and just, and he makes sinners right in his sight when they believe in Jesus.

Images: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons