There is no doubt that we are in a time of change. The West, as a whole, is thrashing about like a teenager in the midst of hormonal angst. It’s not pretty, but it’s also not the end of the world. I continue to hold out hope that our seemingly never-ending drama is a sign of coming maturity. And I believe that Paganism is part of that maturing process.

People who point out that we cannot go on as we have are completely right in their diagnosis. At the same time, they are as fallible as anyone else when it comes to finding solutions. We should know, from our studies of history, that claims of the end-of-the-world usually end embarrassingly.

The Story Thus Far

It is a conceit of our times that we imagine a unified world of great stability and plenty, moving forward toward a time of greater stability and abundance. This is a narrative and a fantasy in the best tradition of the nineteenth-century Western notion of progress. We believe the world is getting better, and get really nervous whenever we see cracks in this rosy picture.

But cracks occur with startling frequency. Shuddering, convulsive change has overwhelmed society with its ever-expanding, always-maddening clip.

The last couple of centuries of change, with their advances and simultaneous feelings of dislocation, give us no real reason to believe the happy story we tell ourselves. We merely hold onto an old self-image because it’s comforting.

In point of fact, the modern movements of social change, whether focused on race, sex, or gender, are (at their base) movements that call out hard and painful truths about who we are. They have called out the lie of “all men are created equal” and asked us (not to put too fine a point on it) to put up or shut up. Paganism is one of these movements.

The Meaning of Paganism

Paganism is a social revitalization movement. It is a return to some semblance of older values, but updated for modern times. The movement is democratic both in its good and bad aspects.

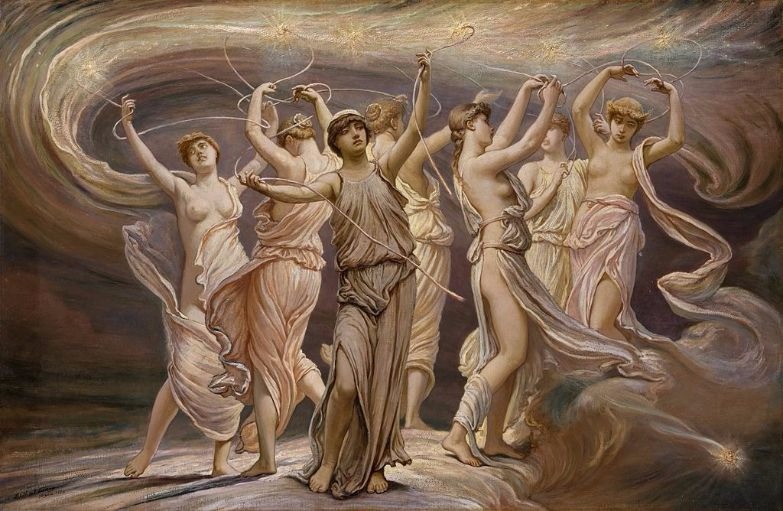

In its broadest sense, the most recent iteration of the Western movement of Paganism is one of these social reform movements. Feminism seeks to redefine the relationship between the sexes; the LGBT community redefines gender; and the racial equality movement, from the NAACP to Black Lives Matter, seeks to challenge the relationships between the races.

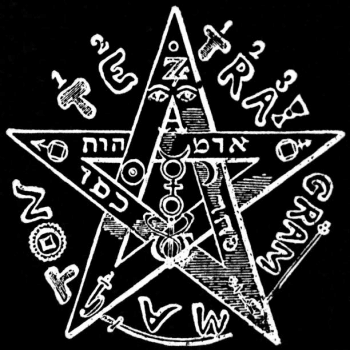

Paganism, writ broadly, seeks to redefine the relationship between humans and the spirit world. In that sense, we are the Western descendants of both the Protestant Christians and the Theosophists. Paganism envisions a “new” kind of human relationship with the spiritual – often drawn on pre-Judeo-Christian or extra-Judeo-Christian sources to inform alternatives.

This is the reason why we often fall on our faces when we ask such questions as, “what do Pagans believe?” “what do Pagans do?” and “what binds the Pagan community together?”

What do Pagans do? We work to fix the broken Western relationship with the world of the spirit.

The Future of Paganism

With all that heavy stuff in mind, it is time to ask the Richard Scarry question: What do Pagans do all day? Understanding that Paganism is a social movement about religion, rather than a religious movement per se, we begin to understand the variation we see.

That is why there is no core of Western paganism, no defining belief or basic set of rules. Paganism is as broad as the seemingly infinite border between Western culture and the world of the spirit. It isn’t just a key to your own spirit and soul, but permission to take full-throated ownership of it and go where and do what you will.

As always, freedom isn’t free. Just because you have permission to walk a greater world, that doesn’t guarantee safety or remove the sting of repercussions from your actions. And to that end, it is often useful to seek out a guide when taking your first steps into the wilderness.

The traditions of Paganism, then, are metaphorical maps of places that have been explored along that boundary. Sometimes we must make promises to those entrusted with the maps before they will share their knowledge with us. Oath-bound knowledge? You betcha. In this context, it makes perfect sense.

A Word of Warning

The territories of Western Paganism are the limits of the human spirit and the human soul. It is a place for questioning everything we have been told. But at the same time, it is also a guide to a spiritual world with the traditional guardrails removed.

As Pagans, we can’t rest on the safe path. We’d best be savvy enough to understand that the world of the spirit is at least as dangerous as the everyday world in which we live. We have to learn to take suitable precautions and live with the dangers that surely exist out there.

Paganism isn’t for everyone. We all know it’s true. But it would be more concise to say, “Paganism isn’t designed for everyone.” Traditional religions are all about systems that (theoretically) work for everyone, keeping people safe from the dangers of the spiritual world.

But if everyday religion is there to teach us that we must never cross the dangerous street (metaphorically speaking), Paganism at its finest will (eventually) teach you how to cross the street at night, dressed in black, with your eyes closed, in a rainstorm. Like I said, Paganism’s not for everyone.

Taking the Long View

Perhaps because the modern Pagan movement is only between three and five generations old, it is difficult for us to think about things in the long view. A lineage might be a dozen people deep over that time, but we have hardly scratched the surface of everything Paganism might be.

As a Pagan, I believe that the work we do – growing the possibilities of the human spirit in ways long lost by the West, or not yet even imagined in the world – is necessary and valuable. I believe that our path forward is paved with virtue. This is not the namby-pamby virtue of the modern world, but the virtue brought by self-cultivation at its finest.

I have devoted much of my adult life to the pursuit of self-cultivation, and what I have learned tells me that the convulsions of society are best viewed with some equanimity.

Equanimity can bring a powerful stillness, but it is not paralytic fear. It is the opposite. With hard work and discipline, we can access a deeper world through a deeper part of ourselves; we can learn not to jump at every rumor of terror but instead deal with the real and meaningful.

In the long run, discipline, equanimity, and depth are necessary to study the world of the spirit. Without them, our work risks devolving into a whole lot of wishful thinking and outraged disappointment. With them, we can bring the power of the sacred back to a world that sorely needs it.