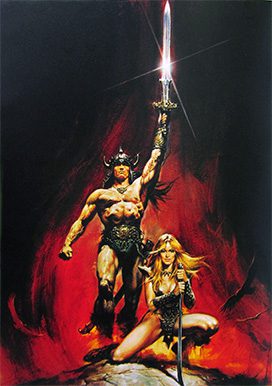

“Between the time when the oceans drank Atlantis, and the rise of the sons of Aryas, there was an age undreamed of.”

Thus begins the 1982 father of all fantasy movies, Conan the Barbarian. Based on the pulp stories of Robert E. Howard, our big-thewed, few-worded, mega-manly anti-hero kills and conquers across screen and page. But as much as we might want to focus on the eponymous protagonist, for me, the real hero in the movie is Akiro, the Wizard of the Mounds.

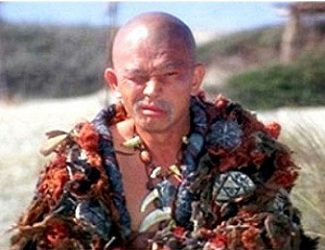

Played wonderfully by Iwamatsu Mako, the wizard serves as Conan’s advisor and chronicler. He does not come off as an urbane, educated man, but he know things and clearly has otherworldly power. When we meet him, Akiro is a hermit, the caretaker of a graveyard for dead kings and warriors – people whose powerful spirits linger on. Thus, he is associated with the underworld. Yet he does not command the spirits; rather he serves them and reaps the benefits of the relationship.

The Wizard of the Mounds embodies the wisdom that guides Conan’s pure strength. Yet, unlike some of the more ethereal wizarding types of literature, Akiro has no interest in blunting Conan’s force. He never tells our young, aggressive jerk-hero to take it down a notch, or that (just maybe) violence only begets violence.

Instead, Akiro directs the warrior to his destiny – avenging Conan’s parents’ meaningless deaths and deposing an evil tyrant. His otherworldly power does not stand in counterpoint to Conan’s worldly might, but instead directs it to its proper end.

Conan the Barbarian as Mythology

Conan the Barbarian is not a subtle piece of literature. It is a broad splash of archetypes across the screen, directed by John Milius in an excellent show, don’t tell manner.(1) And it is very much a product of its times.

To say that the character of Conan is dated is to understate the case. Nonetheless, it is an archetype, and a powerful one. We might even say a little of him lives in all of us – denying it does not make it less true.

But the writing is thicker than we would expect. The movie is not about a two-dimensional Conan, his big sword, and his one-dimensional supporting cast. Every character in the movie is an archetype, making it as much mythology as anything about Zeus on Olympus. Just as much as the Greek myths are about the Greeks and their understanding of the world, the myth of Conan is about us Westerners.

Which brings me back to Akiro, and what he tells us about ourselves. Definitely in literature, and sometimes in the real world too, many wizards (and other magical practitioners) struggle because they hold a belief that the world of magic is not only real, but it is somehow more real than the everyday world. This is a common piece of the perennial philosophy – that the purpose of life is a focus on the spiritual.

The Wizard of the Mounds is the rare fictional practitioner who does not fall prey to this conceit. He practices magic, but clearly does not believe in any more than he can see and touch; it just happens that he can see a lot. Whether through careful writing or blind luck, the character of Akiro manages to stand in the balance – a practitioner but not a believer.

Two Become One

Yes, magic can be used to transcend the world, to set aside this world’s cares and focus on another one. This has long been the lesson of Western magic and religion – a Zoroastrian view that the spirit should be used to step away from the corruptness of the world.

I won’t mince words, here: this view comes from a broken understanding of magic and the world. In order to bring the two back to order, we must draw them together and let them interact. Only then can we have an understanding of the relationship between the two realities.

Trying to use magic to shape the world around us will teach more about the nature of things in a year than we might learn in twenty years of contemplation. There is a place for careful learning, in the beginning. And then there is a long period where we learn by doing.

Although Akiro is a practitioner, he does not have his head in the clouds. This is where the wizard’s character shines as an archetype: he is not overly otherworldly, but stands between the two and guides them into harmony.

Yet Akiro’s harmony is not one of universal peace and love. There is no faith in his world, no inevitability. For all that he deals with very serious things, be they gods or the spirits of the dead, he lacks the pride we expect of the powerful. His harmony is with wherever he finds himself. This makes him a powerful, and different, archetype for a magician.

A Word on Archetypes

There are only a few standard archetypes for male magical practitioners.(2) Most common in literature is the wise old man, kind and well-respected. Then there is the prideful villain who seeks to rise above his station in life. And last there is the hermit who is as much (or more) a part of the land is he is part of society. These are archetypes for a reason. Follow the path long enough, and you may find yourself fitting the mold more than you ever expected.

At the same time, the original wizard archetype is not really about magic. Those who wield magic have long been used as metaphors for peoples’ relationships to power. Will we become the Disney-evil sorcerer Jafar, consumed with ego? Will we serve something greater than ourselves, like Arthur’s wizard, Merlin? Or will we allow power to guide us, like ancient and wise Yoda? These are the same questions everyone who gains even a little power will face in life.

But this becomes confusing when magic is no longer a metaphor for power. How do we understand our lives when magic becomes a literal way of life and the way we give meaning and order to our world? What does it mean to live on the border of the two worlds? How do we talk about our duties to the unseen?

The answer lies in the character of Akiro: he doesn’t. The hermit uses his power, but he hardly ever speaks of it. And his allies, for their part, are happy to benefit but not overly interested.

Where the movie’s villain, Thulsa Doom, uses his power to bend the wills of others, Akiro has power of another kind. He helps Conan master himself and leads him to his destiny. It is not a battle of good and evil, but rather a struggle for growth and maturity. The Wizard of the Mounds is no stereotypical “good guy,” but he makes a powerful mentor.

(1) Conan the Destroyer, the second movie in the series, is a different kind of work. The success of the first movie spawned a whole genre of swords & sorcery imitators, and its sequel had more in common with the rest of these works than the original film. Characters went from archetypes to caricatures, and the direction moved toward more a standard storytelling style that made it much harder to accept the fictional world at face value.

The magic of the first movie is a thing of mystery, more about inducing a state of mind that anything Harry-Potter-esque. The second movie misunderstands the world of the first and gets ham-handed. Magic becomes explicit, and thus loses its terror and mystery.

(2) In culture, gender is one of the basic ways of understanding people. Women get different magical archetypes: the “evil” queen (usually just trying to hold power), the seducer, and the wise woman. Western culture does not treat women who seek otherworldly power too well unless they also know their supposed place. While these archetypes are changing, and the gender aspects becoming more fluid, they still hold heavy sway and probably will for some time.