America’s tribalism is tearing the country apart, and (sometimes it seems) us with it. The danger that we are in is not illusory. But the causes are hard to understand and deeply hidden.

The tribalism that we are experiencing was not thrust upon us. It is the result of an attempt to solve an older problem — the dissolution of the powerful extended family. Tribalism has a time and place, but the way America is using it today is counterproductive.

For all our liminality, Pagans are not immune to this dynamic. Paganism has its own complex relationship to tribalism. Our use of the idea, whether explicit or implicit, relies on Romantic, Utopian ideals of the Noble Savage. We have used these terms for more than two generations, but they are not exclusive to us. Still, they are a hallmark of much of Pagan social structure.

Joining a Tribe

Pagans do not generally use familial terms for membership (brother, sister, father, etc.), a pattern found in Christianity. However, it is clear that “tribal” ideas of membership are prevalent. This is reflected in our strongly tribal attitudes.

Mostly, Pagans do not go in for formal structure, but instead rely on what develops organically.(1) Since at least the 1950s and the public debut of Gardner’s Wicca, Pagans have often relied on the language of the clan or tribe to understand relationships. This was meant to hark back to pre-industrial times, where the extended family was the main unit of social organization.

We have relied on these tribal metaphors even when we have not used the words tribe or clan. These connections were imagined as pre-modern and thus not given to the sway of everyday life. Tribal bonds, we hoped, would be stronger than the rapid change and stresses of the modern era.

For people who felt themselves marginalized in one way or another, the ersatz tribe of Paganism created community. In a world that many felt was becoming both increasingly fragmented and at the same time unified,(2) our small social groups added another level of support.

Those of us called to the Path have long found traditional spiritual groups, like the many Christianities, either insufficient or anathema. With Pagan groups, we no longer needed to face the impossibilities of the larger universe alone. Our small groups created a buffer against immense loneliness.

Kith and Kin

We Pagans have used models of tribal kinship to create what anthropologists call fictive kinship. Our religious community became an ersatz tribe. It supplied bonds of affection, loyalty to the group, respect for elders, and a feeling of membership.

There is no need to go back to prehistoric times to find an era where familial relationships were the main source of “corporate” membership.(3) We only have to go back to before the mass migration of populations to cities — before the Industrial Revolution.

The creation of fictive kinship networks is not essentially Pagan. It has long been the way of “citified” people people to create non-kin social networks. They replace the familial and social stability found in rural lifestyles.

I have my own experience with fictive kinship. When I was growing up, I had numerous “aunts and uncles” that were simply my parents’ closest social circle. As a child I was mystified about how all this worked, but it was designed to bind unrelated people together with a deeper level of loyalty and community.

When we look at American Pagan tribalism with clear eyes, covens are a substitute for what we lost. Our “tribes” fulfill the same role as neighborhood gaggles, gangs, and on up to corporations themselves. They regulate the flow of resources (esoteric knowledge, in the case of Pagans) and share risk in important endeavors. And all of them rely on the same primal instincts inside of us.

Building Perspective

Tribalism, with its trend toward social fragmentation, is an easy target, but it is not the enemy. These small communities fulfill a purpose.

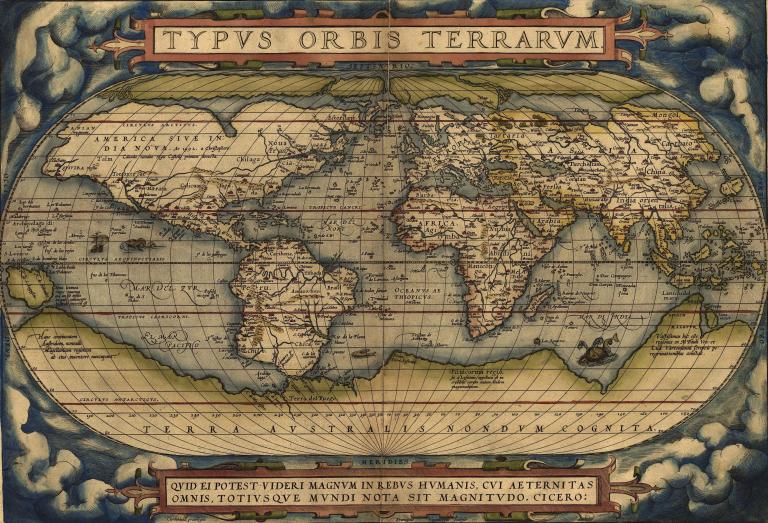

Human existence has changed more in the last century than ever before. In just a couple of generations, everything we know about the world and ourselves has been turned on its head.

My grandfather could remember a time without cars and lived with the horse and buggy and trains. Now we have have transport so fast that it is, for all intents and purposes, global teleportation.

Even my parents were born in a world without medical antibiotics. We have targeted gene therapies.

When we feel lost, or stressed, or confused about how the world works, it is worth remembering that everything we have learned is out of date. When we think we have all the answers and that the path forward is clear, we are fooling ourselves.

In times like this, what we know is less important than who we know. The world is changing so rapidly that it becomes more important to be part of the right group than to know the right things or even have access to the right resources.

We might not know what will be important in five years, but as sure as humans are primates, we know who will be important.(4) In times of instability, social connections trump all other means of creating stability.

The tribalism that we see rising both in America and globally is a corollary of a complex, fluctuating, and unpredictable world. The change we are experiencing is unlikely to slow down unless the whole global system comes crashing down. The groups to which we belong (try to) insulate us from the dangers of change.

Tribal membership is a form of social insurance. Tribes perform a necessary social role. This includes political groups, religious sects, trade unions, alumni associations, and professional organizations. But they are not without dangers.

Making Tribalism Work

We can step back and understand that our tribes (religious, social, professional, and political) are not the problem. That does not solve the challenge of getting them to work together.

Our culture is like a giant relationship, and it only works when we work at it. The more we worry about only ourselves and our own tribes, the more we destabilize our country, and the more given we are to panic and mob mentality.

While we would like to blame this or that, us or them, we have done this to ourselves. No one has led us astray; we have simply swallowed too much change and given ourselves existential indigestion.

Working together is the only way to get out of this mess. But when it comes to a time of change and panic, everyone is making sure that their own needs are met first, that their family is second, and their tribe last. We believe that the nation is someone else’s responsibility. We could not be more wrong.

The danger is not from one person, or one group, or some external enemy. We do not need “America First” against the outside world, but to moderate the tribal behavior inside it. Americans have lost track of Benedict Anderson’s imagined community of nationalism, and moved deep into some post-truth morass.

The Tree of Wisdom

In these difficult times, the polarization of politics is seeping into the well of Paganism. Paganism is a world of tiny cross-pollinated tribelets, and there is great temptation to align our spiritual experience with our politics. But to argue that one side is right, and that the other is wrong, is to decide who has what they need and who does not. That is the role of politics, not religion.

Paganism worships at a metaphorical tree of wisdom, and the tree’s roots go deep and its leaves reach to the sky. This “tree” goes deeper than America, deeper than culture, deeper than humanity. If we identify with that tree, then we will come to understand that the tribalism in America is a squabble over resources in trying times.

We must, then, align our politics with our spiritual experience, rather than the other way around. And we must encourage others to do the same. Pagan or not, one path out of this political tribalism is to reemphasize our common bonds as people.(5) We do not need to abandon our tribes, but we must learn to see ourselves as part of something larger than our affiliations.

(1) Social structure that develops “organically” among humans is, perforce, primate behavior. A close analysis shows that Pagan organization mimics both band and tribe structures of sociopolitical typology.

On a related note, the attempts of the polytheist community a few years back to add more structure followed this same path, attempting to build the priesthoods generally associated with chiefdom (kingdom)-level organization. While they were frustrated in their efforts, we can see that this was probably caused by an inability to gather significant resource control to create hierarchies of distribution.

(2) Yes, it is possible for the world to become both more isolating and more unified at the same time. Looking at humanity as a whole, advances in technology have brought people together. It has not, however, made them less human.

Globality has not led to some fabled “kumbaya” moment, but rather to increased tribalism and instability. The current global trends toward authoritarianism and conflict are nothing new, but a pendulum swing against some secular Utopian unification narrative.

(3) “Corporate” membership here is used in the anthropological sense, relating to membership that affects social safety, economic status and opportunity, education, and access to resources from land to marriage partners.

(4) Even if everything we think we know about society changes, the hierarchy we depend on for stability is unlikely to change entirely. Yes, powerful people come and go, but not as much as we would think. We like to imagine that low-status people can rise and high-status people can fall, but that is the exception rather than the rule.

(5) To anyone who claims that “our” side does that and “their” side does not, I ask that you reassess your underlying assumptions. Compassion for the other does not mean trying to turn them into a reflection of yourself. If religion is to be more than a language of membership, then we will need to seek the meaning beyond the words themselves.