Pope Joan was a woman disguised as a man who allegedly became Pope John VIII in the year 854. Let me be clear right now that this never happened. Yet the story of Pope Joan, the woman pope, was so widely believed that for a time it was written into official church history.

According to author Eamon Duffy (Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes, Yale University Press, 2015), the story of Pope Joan first appeared in a Dominican chronicle written in 1250. Dominican friars were called the Preaching Friars, and it seems the preaching Dominicans spread the story all over Europe. And the story grew more detailed over time, as legends will. Later in the 13th century a Dominican named Martin of Troppau wrote a book called Chronicon pontificum et imperatorum (“Chronicle of the Popes and Emperors”) that gave the most detailed version of the story of the woman pope to that time. Pope Joan, the story goes, was an Englishwoman who was educated in Mainz and passed herself off as a man. Joan became a monk and eventually was elected Pope in 854, replacing St. Leo IV. (In fact, St. Leo was Pope until he died in 855 and was replaced that same year by Pope Benedict III.) And note there is nothing about Pope Joan in any record from 854 to 1250, which ought to have raised suspicions.

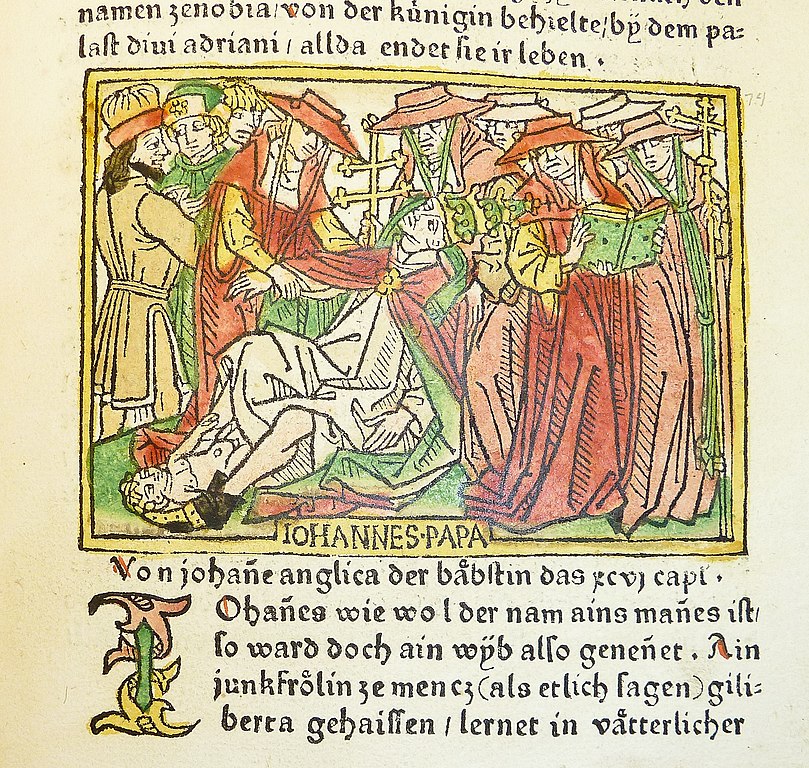

The story of Pope Joan continues: The “popess” was hopelessly promiscuous and had a multitude of secret lovers. But one day in 857, during a solemn procession in Rome, the jostling of the crowd set her into premature labor. Pope Joan gave birth in front of everybody. Whoops! In one version of the story, the crowd then tied Pope Joan’s feet to a horse’s tail, and she was dragged through the streets and stoned until she died. In other versions, she was lynched on the spot. In most versions she was buried that day, where she died. Another version let her live for a time, in confinement. The baby grew up to be Bishop of Ostia, who gave her a tomb in his cathedral.

Pope Joan in Church History

“No one during the Middle Ages questioned the historicity of the myth,” writes Eamon Duffy, “and as the legend established itself it was pressed into service by people with axes to grind and points to prove.” For example, in the 14th century Pope John XXII condemned Franciscan teachings on poverty. The Franciscan William of Ockham — a man admired to this day for his keen and logical mind — responded, using the example of Pope Joan in his criticism of John XXII. Popes can be false, as Joan was, and false popes can deceive anyone, Ockham said.

So it was that Pope Joan became part of the accepted history of the Popes. Her portrait was even displayed wherever there was a gallery of portraits of popes. By the mid-15th century, it was widely believed that new popes went through a ritual of allowing themselves to be groped to prove they were male. This would qualify as an “urban legend” today, I believe. And, of course, during the Reformation, in the 16th century, Pope Joan was cited frequently by Protestants to undermine the authority of the popes.

Pope Joan remained part of official history until the 17th century. Then a French Calvinist scholar, David Blondel, “worked patiently through the successive versions of the legend and demonstrated its impossibility from start to finish,” writes Eamon Duffy. Other Protestants were angry with Blondel for this, because they dearly wanted to believe the corrupted false pope story was real. It took a long time for the legend to die. But Pope Joan was dropped from official church history after that.

Lessons for Today

People of centuries ago were not reliable record keepers. And what records that were kept were often lost in fires and floods and wars. The further back one goes, the more the puzzle of history comes with missing and ill-fitting pieces. The work of historians sometimes can be like trying to draw a picture of a long-extinct animal when all you have to go by are some tail bones and a hoof. Further, even solemnly kept official chronicles from long ago present legends and myths as history. This was very common until the 17th and 18th century or so, when historians like David Blondel began to apply critical thinking to historical records to sort out what might have really happened from what couldn’t possibly have happened, even though people believed it happened.

But it’s also the case that the legend of Pope Joan wouldn’t have lived all those centuries if people didn’t want to believe it. Clearly there was something about the story that checked a lot of boxes. Distrust of papal authority? Check. Misogyny? Check. Old-fashioned prurience? Check. Today, in the Age of Misinformation on the Internet, you probably can think of current, common beliefs that are just nonsense. But if people really want to believe that nonsense, there’s no dissuading them.

And the moral is, it’s most important to apply skepticism to information that you dearly want to believe. Anybody can be skeptical of ideas or doctrines or stories that they don’t want to believe. The real test of a true skeptic is the ability to be skeptical of information that confirms one’s biases, and which one wants to believe. So watch out for that.