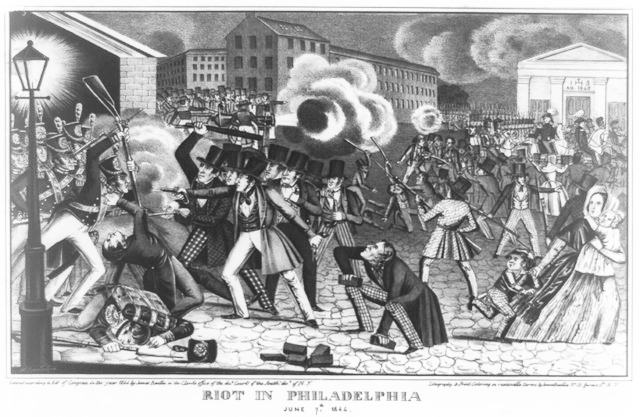

The Philadelphia Bible Riots of 1844 are also sometimes called the Philadelphia Nativist Riots. By whatever name, the Philadelphia Bible Riots were deadly and destructive. It’s estimated 20 people were killed in the violence and many more injured. Two Catholic churches, a seminary, and several private homes were set on fire and destroyed.

The reason? A false rumor that Catholics were scheming to have the King James Bible removed from public schools. The Catholics in this case were recent immigrants from Ireland. At a time when ugly claims about immigrants are having a big impact in the United States, I thought it might be useful to look at similar episodes in our nation’s past. And the Philadelphia Bible Riots of 1844 were a particularly nasty episode.

Anti-Catholic Nativism

There had been Irish Catholics in Philadelphia going back to colonial times. It’s believed the first Saint Patrick’s Day parade in the city was held in 1771. However, most of the first Irish immigrants in Philadelphia were Protestant Scots-Irish. Beginning in the 1780s more Irish immigrants came to Philadelphia. Many of these were cottage textile workers who had lost their livelihoods to newfangled steam-powered machinery in British textile mills. Others were laborers looking for opportunity. Most of these Irish were Catholic, and the increasing presence of Catholicism in Philadelphia stirred anxiety in the mostly Protestant natives. It also rekindled the old antagonism between Catholic and Protestant Irish from the old country.

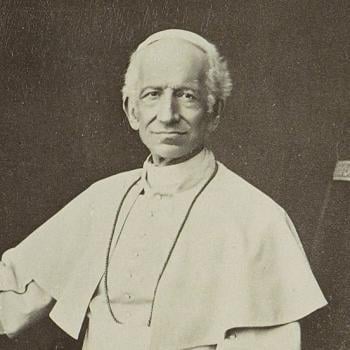

Anti-Catholic nativism was rampant in much of 19th century America. This was less about doctrinal disagreements than the fear that Catholics were more loyal to the Pope than to the United States. They were seen as a threat to democracy. This is a belief that lingered in the U.S. well into the 20th century. When John F. Kennedy was the Democratic nominee for president in 1960, he had to reasure voters he took no orders from the Vatican. “I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute; where no Catholic prelate would tell the President—should he be Catholic—how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote,” Kennedy said.

How the Bible Became an Issue

Bible readings were a common part of U.S. public school education in the 19th century. The schools in Philadelphia used the King James Bible, which was considered a “Protestant” Bible to Catholics. The children were also taught Protestant hymns and prayers. In 1842 Philadelphia’s Catholic Bishop, the Irish-born Francis Patrick Kenrick, wrote to the Board of Controllers of Public Schools asking that Catholic children be allowed to read from the Douay–Rheims Bible approved by the Catholic church. He also requested they be excused from Protestant hymns and prayers. This mild request kindled nativist alarm in Philadelphia, to the point that several Protestant clergy formed an American Protestant Association to defend America from “Romanism.”

Matters came to a head in the Kensington neighborhood of northeast Philadelphia in 1844. This neighborhood was home to a growing population of Irish Catholics. In February of that year, a school director who happened to be Catholic suggested that Bible readings be suspended until some compromise could be worked out. And this touched off a virulent rumor that the King James Bible was going to be banned from the public schools. Nativists by the thousands rallied in Philadelphia’s Independence Square to denounce this supposed outrage.

Note that 1844 was an election year, and several local politicians began to demagogue the issue to drive their nativist supporters to the polls.

The Philadelphia Bible Riots of 1844

On May 3, 1844, a mob of nativists marched into Kensington but were chased away. They returned on May 6, and during the street brawling a nativist man named George Shiffler was shot and killed. Shiffler became a martyr to the nativist cause. The violence intensified, and by the end of the day several more men had been shot, three fatally. The next day troops of the Pennsylvania state militia arrived to keep the peace. The nativist mob responded by starting fires. On May 8, several private homes, two Catholic churches, and a Catholic seminary were burned beyond saving. The violence ended on May 10 after more militia, some regular army troops, citizen posses, and city police were finally able to stop it.

For a few weeks there was an uneasy peace. Nothing had been resolved. Then violence broke out in Southwark, an independent district south of Philadelphia and a nativist stronghold. It was discovered a Catholic priest’s brother had stockpiled weapons in the basement of a church in Southwark. On July 5 thousands of nativists surrounded the church and demanded the weapons. Militia arrived the next day to break up the mob. Some militia remained to guard the church and some nativist prisoners within it.

On July 7 the nativists returned, this time with cannons, and forced the militia to surrender the church and its prisoners. When more troops arrived the mob attacked them with bricks and stones. The militia responded with gunfire. The battle that followed lasted into the evening, both sides firing cannons. Four militia men and more than a dozen rioters were killed, and many more wounded. By the next day thousands more militia had arrived from other parts of the state, and the riots were over.

The Philadelphia Bible Riots of 1844: Epilogue

The riots of 1844 persuaded many that the city of Philadelphia needed a larger police force. In 1845 the Pennsylvania legislature passed a law requiring one police officer for every 150 inhabitants in major cities. The Philadelphia police district was reorganized so that it covered the entire metropolitan area, including Kensington and Southwark. Also, nativists did very well in the November elections.

The Bible issue remained unresolved for a very long time. The role of Irish Catholics in Philadelphia also was unresolved. Note that 1845 marked the beginning of the Great Famine of Ireland. It’s estimated that nearly two million Irish immigrated to the U.S. because of the famine.

In 1956, a student in a public high school near Philadelphia protested his school’s daily Bible readings and prayer. The student’s name was Ellery Schempp, and he thumbed through a borrowed Quran instead of attending to verses from the King James Bible. This protest eventually ended in a landmark Supreme Court decision. In Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203 (1963), the U.S. Supreme Court voted 8-1 that required Bible readings and prayers in a public school were unconstitutional. See “The Problem With Bible Readings in U.S. Public Schools” for the whole story.