Who were the Aryans? The Aryans were an ancient people who spoke Sanskrit and gave us what are believed to be the world’s oldest living scriptures, the Vedas of Hinduism. They were “pastoral,” the anthropoligsts say, meaning they herded livestock. They were nomads who left us no cities to excavate or great monuments to admire. The literature they left us suggests they were a patriarchal and sometimes violent people. They prized their horses and probably introduced the horse-drawn chariot to India, about 1500 BCE, give or take. But beyond that the picture is very blurry.

It’s important to understand that today’s scholars do not consider the Aryans to have been a racial or ethnic group. This flies in the face of what you may have heard, I know, and I’ll be addressing that. But current thinking in academia is that the Sanskrit word arya, which means “noble” or “distinguished,” was a social designation. The distinguished ones spoke a common language and shared many cultural norms.

The Aryans: Early History

There has been much speculation about where the Aryans originated. Some theories place their hypothetical, long-ago origins in the territory that is now Ukraine, about 3000 BCE, although I don’t know how widely accepted that is. Historians do seem reasonably (but not totally) certain that the Sanskrit-speaking, nomadic people identified as Aryans first entered the Punjab from Central Asia about 1900 BCE. Over the next few centuries they crossed the Hindu Kush and reached the Ganges River by about 1000 BCE. Eventually they spread across the Indian subcontinent.

It’s believed that as they migrated, Aryan men often took wives from the not-Aryan local populations. So if they (hypothetically) started out with some racial homogeneity, that didn’t last. Note that this migration happened in waves and over long periods of time. My impression is that the Aryans were not exactly a unified people but probably were splintered into many sub-groups or tribes. Sanskrit itself developed into many diverse locally spoken dialects, and in time classical Sanskrit was reserved for religious rituals and sacred literature.

The Aryans: The Importance of Sanskrit

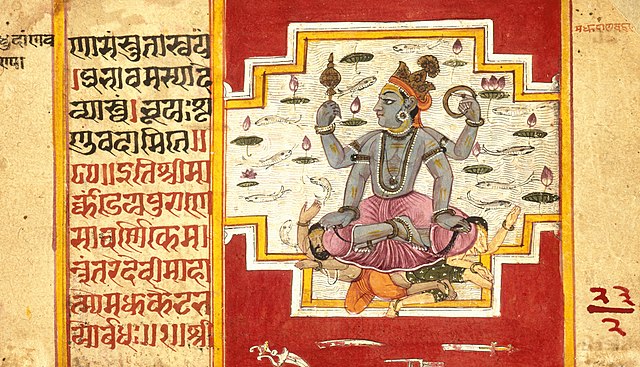

It’s likely few people would care about the Aryans were it not for Sanskrit. Classical or Vedic Sanskrit is the religious language of Hinduism to this day. Hinduism’s rich sacred literature began with the four Vedas, which are mostly collections of hymns. The oldest is the Rig Veda, believed to have been composed between 1500 and 1000 BCE. And it’s very possible parts of it are even older. The “Vedic” literature includes other texts beside the Vedas, including the deeply philosophical Upanishads. There are also some significant not-Vedic texts, which include the epic poems, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. And within the Mahabharata is the much-beloved Bhagavad Gita, one of the jewels of the world’s religious literature. The Patheos religion library has a good article on the sacred texts of Hinduism that explains all this in more detail.

The trouble started, so to speak, when European scholars began to study Sanskrit in the late 18th century. They expected Sanskrit to be utterly different from European languages. To their astonishment, it was not. It’s understood today that Sanskrit and European languages had a common ancestor, called the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language, which appears to be most closely related to Sanskrit, Mycenaean Greek, Ancient Greek, and Hittite. Traces of Sanskrit found their way into Latin and the Germanic languages as well.

This obvious affinity between Sanskrit and European languages made the 18th century European scholars nearly giddy. The British philologist Sir William Jones wrote in 1786,

The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source. …

Speculation Goes Off the Rails

Jones and other language scholars translated the Sanskrit literature into European languages. These translations influenced many European intellectuals, such as Arthur Schopenhauer, and American Transcendentalists, such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. They also sparked a lot of curiosity and speculation about this wonderful ancient language of Sanskrit and the people who spoke it.

Much of Europe in the 19th century was obsessed with colonizing the rest of the planet. It wasn’t long before this colonialist imperative and romantic notions about the Aryans — who were assumed to be European — began to merge. Europeans fancied themselves the original bringers of civilization itself. Friedrich Max Müller (1823-1900), a German-born professor of Sanskrit at Oxford University, imagined that the Aryans were the “rulers of history” who had “a mission to link all parts of the world together by chains of civilization, commerce, and religion.” By some coincidence, this was how European colonialists saw themselves.

The Nazis and the Master Race

Many 19th century western scholars and popular writers began portraying the Aryans as some sort of primordial “master race.” Theories about the Aryans soon were woven into their belief in the natural superiority of White people. For example, in 1853 an influential French aristocrat named Arthur de Gobineau published An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races, in which he identified the Aryans as the White race. Only Whites/Aryans were capable of true civilization, de Gobineau argued, and the mixing of races leads to cultural decline. And yes, this is nonsense on steroids, but de Gobineau’s ideas were widely embraced, especially in North America and Germany.

In the early 20th century such theories as de Gobineau’s influenced Adolf Hitler and other German fascists. The Nazis believed that Aryans were not just European but Nordic, fair and blue-eyed. Hitler was obsessed with “racial purity.” He used the word “Aryan” to mean “the pure German master race” or Herrenvolk. His “Aryans,” Hitler believed, were entitled to rule the world. And he adopted the swastika as the symbol of Aryan power. Swastika is a Sanskrit word that means “well-being,” and for millennia the hooked cross represented benevolence until Hitler made it a symbol of nightmares.

But by the 1930s, even as Hitler was still planning world Aryan dominance, archeology and scholarship began to revise most of the 19th century theories about the Aryans. And this is work that continues.

Setting the Record Straight

It’s the fascist meaning of “Aryan” that seems to still live in popular imagination, which is a shame. A lot of the old 19th century pseudo-scholarship that portrayed the Aryans as noble White people spreading civilization in the ancient world is still in print, and naturally it’s been posted on the Internet as well. Occasionally I run into people who still believe it.

The real Aryans, whoever they were, deserve to be remembered for their beautiful language and the richness of their religious literature. But it’s also the case that in many respects they lagged behind other civilized people. They were nomads, remember, not civilization-builders. Aryans were still living in straw huts or other temporary shelters while many other people were building elaborate cities, and long after the Egyptians had erected the pyramids. And if there were artists among the nomadic Aryans, their work has been lost.

It also appears there was no written Sanskrit until some time after 500 BCE or so. The Vedas had been preserved for generations through an oral recitation tradition. How then, you might ask, do we know how old they are? As I understand it, scholars estimate the ages of the Vedas from descriptions of geography and astronomy, and possibly also place names that can be matched with known history.

By the mid-1st millennium BCE the descendants of the Aryans who had reached the Ganges were living in permanent communities. Thoroughly inter-married with the earlier inhabitants of the region, they had taken up commerce and agriculture and ceased to be nomads. They now spoke various dialects of Sanskrit among themselves. Only the priestly caste, the Brahmans, used Vedic Sanskrit as they recited the hymns and performed the rituals. Generations to come would create in India a vibrant and spiritual culture founded on the ancient Sanskrit literature, and they would give this to the world.