There’s a common assumption that laws are based on morality and morality comes from religion. Therefore, laws have a religious basis. Further, whatever is widely considered to be immoral ought to be illegal. In truth, not all manner of things immoral are illegal (for example, lying to your spouse about where you were last night). It’s possible that there are behaviors that are illegal but not immoral, although off the top of my head I can’t think of a good example. But it might be useful to understand where our ideas about law and morality really come from, and how much either is tied to religion.

Let’s start with another question: Which came first, civilization or law? I understand that everywhere the first civilizations emerged in the ancient world, on all continents and in both hemispheres, there were some basic rules or laws that emerged with them. These included restrictions on theft and homicide, for example. If you think about it, such restrictions made civilization possible. Without them, we’d still be huddled in caves with our immediate families, guarding our lives and our flint arrowheads from those people in that other cave. Communities, and civilization itself, couldn’t exist.

Historians propose that as early human communities formed, there must have been some agreed-upon norms or customs about correct behavior that eventually were codified and made into laws. It’s also believed that the first civilizations may have organized around shared spiritual beliefs. Rulers claimed authority to rule from gods, sometimes by claiming to be gods themselves. There was no separation of church and state way back when. So law, morality, government, and religion all emerged from the same primordial soup, so to speak.

Law and Morality: The First Laws

Very early legal codes, such as that of the Mesopotamian King Ur-Nammu (ca. 2100–2050 BCE), outlawed murder and theft and most adultery. The oldest complete law code we have is that of Hammurabi, who reigned in Babylon from 1792 to 1758 BCE. In the code of Hammurabi we see many laws dealing with commerce, property, and contracts. Civilization had grown more complex.

I get the impression from reading Hammurabi’s laws that the code probably grew as new situations came up. For example, what happens if a person loses a possession, and then finds someone else with that possession? And the second person swears he didn’t steal it but bought it from a merchant? If the purchaser can produce witnesses who will back up his story, the purchaser pays no penalty. But then the merchant has to be executed. (Hammurabi was big on the death penalty. If someone accused another of a capital crime but failed to prove guilt in court, the accuser was executed. This no doubt discouraged nuisance lawsuits.)

In other words, the laws in Hammurabi’s code were mostly of a practical nature and dealt with very worldly situations. There’s nothing explicitly religious about the code. At the same time, a prologue to the code explains that the gods of Babylon gave Hammurabi the authority to rule, and the laws themselves came from Shamash, the god of justice. But with respect to Shamash, Hammurabai’s laws were all about maintaining civil order and had no obvious connection to any divine purpose.

Law and Morality in Early Religion

It’s believed prehistoric religion was a sort of rudimentary shamanism. In the neolithic period, which began about 10,000 years ago, people took to living in more complex, permanent communities, and both government and spirituality began to be organized and codified. Shamans and priests were an elite who guided ordinary people through life’s passages from birth to death. But as near as we can tell, the primary focus of this early spirituality was to please gods, who would provide good weather, bountiful harvets, and victory in battles. Were these early religions also concerned with correct behavior, or what we would call morality? I don’t believe that’s something that is clearly understood.

This brings us to the Ten Commandments, which may be the earliest laws to be associated with religion. The story of Moses receiving the Commandments traditionally is dated to about 1300 BCE, which you might notice is quite a bit after Hammurabi, never mind Ur-Nammu. Regarding how the Ten Commandments came to be preserved in scripture, I recommend the book Who Wrote the Bible? by Richard Elliott Friedman. The Torah, or Pentateuch, or first five books of the Old Testament, had multiple authors who told conflicting stories. These stories were editorially smoothed out a tad in the final version of the Torah, which probably came together during the Persian period, 539–332 BCE. Portions of the story could be much older, of course.

Over the years a number of scholars have suggested the Ten Commandments themselves were written in the style of the many legal codes of the region inspired by Hammurabi. It would appear that the worldly, practical law came first, and the religious one came after. And people who insist that all laws originated with the Ten Commandments are mistaken on several levels. See “The Ten Commandments and the Origins of Law.”

Law and Morality and Religion

Morality is most often defined as a system of values and principles concerning right and wrong behavior. But do see the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy for a nerdy explanation of why morality is not a simple thing to define. Further, I don’t think we can know clearly how the early spiritualities were connected to ideas about morality. I do think we can say that most of today’s ideas about the values and principles underlying morality were formulated in the 1st millennium BCE, give or take.

It was during this period that prominent sages and philosophers throughout the ancient world moved beyond correct rules and rituals and began to promote the values and principles of morality, such as compassion, kindness, and good fellowship. An early example that possibly dates to the 2nd millennium BCE is from the Torah or Old Testament. “You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against any of your people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself: I am the LORD” (Leviticus 19:18). This is included in one of the “alternate” versions of the Ten Commandments.

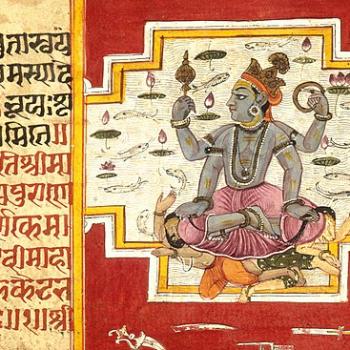

The later Vedic period of India (roughly 1000–600 BCE) gave us the principle of ahimsa, causing no harm to other living beings. The concept of dharma, which in Hinduism is the moral and ethical principles, duties, and laws that govern how people should live, greatly expanded in the 1st century BCE. Confucius (in Chinese, Kǒngzǐ), whose moral philosophy guides much of Asia to this day, lived approximately from 551 to 479 BCE. He possibly was a contemporary of the Buddha, who also is thought to have lived in the 6th to 5th centuries BCE. The Buddha’s ethical teachings emphasized the culvivation of loving kindness and compassion. Socrates (ca. 470–399 BCE) began a tradition of moral philosophy in ancient Greece that still permeates western thought. In the centuries that followed many great teachers and philosophers expanded on these early foundations, of course. But I would say that all of the basic elements of the principles of morality came together in the 1st millennium BCE. (See also “What Was the Axial Age?“)

Law and Morality: Conclusions

History appears to tell us that law and morality often traveled different paths. I tend to think of law and morality as two circles of a Venn diagram. They overlap a lot, but they aren’t exactly the same thing. Law as enacted and enforced by government is about maintaining civil order. Morality is — or should be — about harmonious relationships and communities. And the world’s religions tend to promote morality as essential to achieving salvation or enlightenment.

It has to be acknowledged that there are plenty of examples of “morality” causing sufferng and oppression. When moral ideas are based on bigotry and ignorance, things can get ugly. And while morality has long been associated with religion, I don’t think morality depends on religion. But maybe that argument can wait for another post.