Buddhism and the California Gold Rush may be two things that don’t seem to go together. But it was the Gold Rush that first brought Buddhism to California. The California Gold Rush began in 1848, when gold was discovered at a sawmill north of San Francisco. The first Buddhist temple in North America — and possibly the first outside of Asia, as far as I know — was built in San Francisco in 1853. And the second event came about because of the first.

California had just become a U.S. federal territory in 1848, as part of a treaty between the United States and Mexico at the end of the U.S.-Mexican War. It’s estimated only about 160,000 people lived in California at the time. Most of these were Native Americans. The remainder included Californios (people of Spanish or Mexican descent), plus a few people from the eastern U.S. and Europe. At the time, traveling to California from just about anywhere was a months-long, dangerous journey that few wanted to make.

But by 1849 there were 80,000 prospectors, known as “Forty-niners,” in California, panning and digging for more gold. By the time the Gold Rush was over in 1855, 300,000 people from around the world had arrived to “strike it rich.”

Buddhism and the Gold Rush: The Chinese Miners

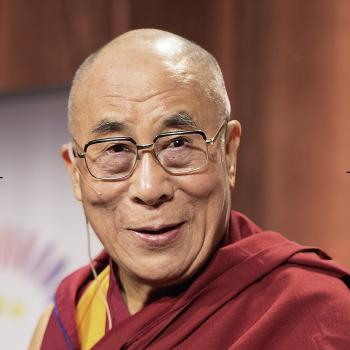

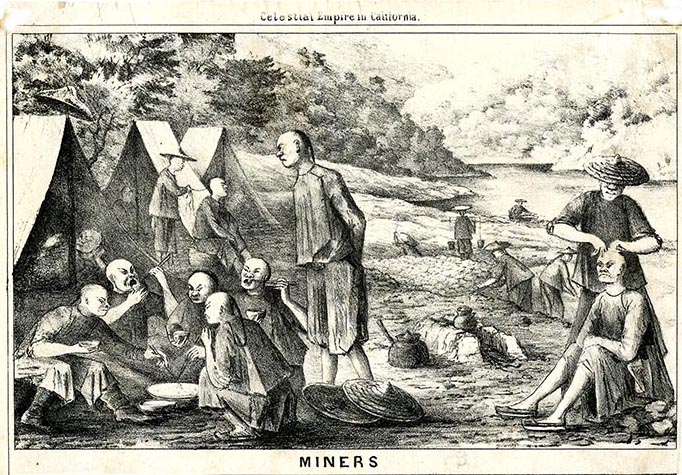

There may have been a handful of Chinese immigrants in California before the Gold Rush began. More began arriving in 1849, mostly from the Chinese port city of Guangzhou, then called Canton. Guangzhou was in a part of China still recovering from the damage of the First Opium War, and times were hard. When the Taiping Rebellion began in 1850, getting out of China must have seemed an even better idea. Chinese men bought passage across the Pacific to gam saan, the “gold mountain” of California. At the height of Gold Rush immigration in 1852, about 30 percent of all newcomers to California were Chinese.

The plan had been to make money in the gold fields and send it back to China, so that wives and children could join the men in California. But the money came more slowly than they had hoped. The Chinese faced hostility from other miners and had to settle for less productive areas to mine. Working together, they did find some gold. But many realized they could have a more steady income from other kinds of work — as cooks, construction workers, fishermen, laundrymen, shopkeepers.

Cut off from their culture, the Chinese in California did their best to replicate it. They formed associations based on the districts from which they came. These came to be called the Six Companies, and they formed the basis of social life for Chinese immigrants. The Six Companies helped newcomers get settled. They also helped maintain connections to China and the families left there. And they organized observances of festivals and religious life. It was one of the Six Companies that built the first Buddhist temple in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1853. Many more soon sprang up in Chinese-American communities.

The “Joss Houses”

Most of these early temples would more accurately be called Buddhist-Daoist-Confucian temples, because they contained elements of all three traditions, following popular religion in China. It was not at all unusual to find images of the Buddha and Daoist gods on the same altars in China. Many temples were predominantly Daoist; others were more Buddhist. Often these early California temples were not stand-alone buildings but occupied the top floors of buildings owned by the Six Companies. Of the stand-alone temples, some were simple wooden shacks, but others were built in distinctively Chinese style and elaborately decorated. At first there were no Chinese priests or monks of any sort, and I don’t know for certain when the first Chinese clergy arrived. But the temples gave the men a place to connect to their ancestral cultures and find dignity and meaning in their lives.

In the 1870s or so, both Chinese and not-Chinese Californians began to call the temples “joss houses.” The reference books all say “joss” is based on a mispronunciation of the Protuguese deus, or “god.” In popular vernacular, incense sticks also became “joss sticks.” The joss houses were often targets of anti-Chinese terrorist organizations, such as the Order of Caucasians. Many joss houses were deliberately set on fire and destroyed.

In his book How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America, Rick Fields describes two large incense holders still in use in a Nevada City temple.

The incense holders, brought from China at great expense by the Chinese miners who worked in the surrounding Sierra Nevada foothills, are still in good condition — except for a few jagged bullet holes punched through the soft metal, the result of a few random rounds fired into the local joss house by cowboys leaving the saloon on a Saturday night a century ago.

Postscript

The building that housed the first Chinese temple in the West, built in 1853, was destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire. The oldest joss house still standing in the U.S. is in Weaverville, California, and it was built in 1874.

Chinese immigrants made significant contributions to California’s economy and supplied most of the labor that built the transcontinental railroad. Even so, in 1882 the U.S. Congress passed a Chinese Exclusion Act that barred immigrants from China. It would not be repealed until 1943.