The Buddhist nuns of Japan, like their sisters in other parts of Asia, struggled against patriarchy for centuries. There are many ancient tales of women leaders and warriors in Japan, which suggests Japanese culture wasn’t always patriarchal. And as we’ve seen, after Buddhism was introduced to Japan the first monastic ordinations were given to women.

Nevertheless, nyonin kinsei―“no admittance to women”―was the rule in Japan from at least the 8th century and several centuries after. This meant that nuns were barred from participating in public ceremonies. They were not allowed to enter most areas of men’s monasteries for any reason. Women were considered “unclean” and incapable of realizing enlightenment. It’s not clear where nyonin kinsei originated―one suspects the influence of Confucianism―but it spread to Shinto as well as Buddhism and to other parts of Japanese culture.

A few male teachers spoke on behalf of women. For example, Eihei Dōgen (1200–1253), founder of the Soto Zen school, wrote an essay titled Raihaitokuzui (Receiving the Marrow by Bowing) in which he said that only fools do not bow and acknowledge a woman who has “attained dharma,” or realized the wisdom of the Buddha’s teaching. But through most of the history of Buddhism in Japan it was difficult for women to receive the same teachings as men.

Remarkable Women

As in China, we have far fewer extant records of Japanese Buddhist nuns compared to the records of monks. What records we do have can be surprising. For example, Kakuzan Shido (1252–1305) was the wife of Hōjō Tokimune (1251 – 1284), a regent of the Shogun. For a time, Hōjō Tokimune was the de facto ruler of Japan. When Hōjō Tokimune died, Kakuzan Shido took nun’s ordination and founded a temple/convent called Tokei-ji in Kamakura. Tokei-ji provided a way for Japanese women to leave unhappy marriages. Once inside, women were out of reach of husbands, and if they remained two or three years, they could leave with a certificate from the temple that declared them to be unmarried. To this day Tokei-ji is called the “divorce temple” in tourist guidebooks.

Mugai Nyodai (1223–1298) was accepted as a student by a male Zen master named Enni Ben’en, which was unusual. And many of the monks in Enni Ben’en’s temple didn’t handle it well. She found herself the center of much unwanted attention. To silence her detractors she mutilated her own face with a hot iron. Only then was she no longer considered a “distraction” to the monks.

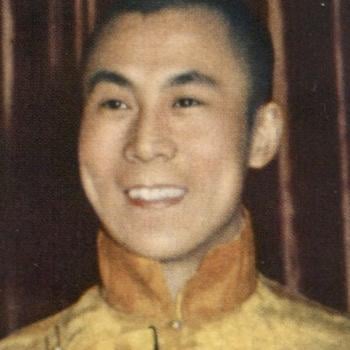

Mugai Nyodai was the first Japanese woman recognized as a master of the Rinzai Zen school. However, she was erased from records and nearly forgotten. We know about her today because the scholar Barbara Ruch discovered her portrait among those of other temple abbots, and Ruch started digging. For more on these and other remarkable women, see Zen Women: Beyond Tea Ladies, Iron Maidens, and Macho Masters by Grace Schireson.

Buddhism in Japan diverged from Buddhism in the rest of Asia in several ways, which led to unique complications for women clergy.

The End of the Vinaya in Japan

In most of Buddhist Asia there is a huge controversy over the full ordination of nuns; see The Buddhist Nun Controversy. In brief, in most schools of Buddhism nuns and monks are trained and ordained according to the rules of the Vinaya Pitaka. The full ordination of nuns requires a quorum of fully ordained nuns and monks to be present. Where the nuns orders have died out, or were never established, full ordination is denied to women. For centuries the only fully ordained Buddhist nuns anywhere were in east Asia. This lineage of nuns began in 5th century China; see Chinese Buddhist Nuns: A History of Perseverance.

However, beginning in the 8th century some of the monastic orders in Japan stopped using the Vinaya entirely and adopted simplified rules. This practice spread to nearly all of Japanese Buddhism eventually. For this reason, Japanese ordinations of either monks or nuns often are not respected elsewhere in Asia. Traditional Vinaya ordination was still available in Japan for several centuries, offered by the Risshū, or Vinaya, sect. But there is only one Risshū temple in Japan today.

The simplified rules were adapted from a scripture called the Mahayana Brahmajala Sutra. It’s believed this sutra was composed in China in the 5th century. These new rules left out a few things. For example, the Vinaya has hundreds of rules that touch on celibacy and avoiding sexual gratification. But the Brahmajala Sutra provides no guidance on monastic celibacy.

The government of Japan took on the job of enforcing monastic celibacy, along with head shaving and the proper wearing of robes. So in many ways nothing much changed for Japanese nuns and monks — until, beginning in 1868, the government enacted sweeping new policies that completely upended Japanese Buddhism. Among other things, the government declared that monastics were free to marry, not shave their heads, and wear whatever they liked. This change had a massive impact on Buddhism in Japan; see How the Meiji Era Changed Japanese Buddhism.