The 26 martyrs of Nagasaki were Christian missionaries who were crucified in Nagasaki, Japan, on February 5, 1597. Among these were six Franciscan priests, most of them Spanish. The remainder were Japanese Catholic converts, at least one of whom had been ordained by the Jesuits. Three were young boys who had served as altar attendants. The martyrs of Nagasaki were executed on the order of Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598), a powerful samurai warlord who is credited with unifying Japan after a period of chaos and anarchy. He is also remembered for his ruthlessness and cruelty.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s persecution of Christians was just a beginning. Christianity would be officially banned in Japan in 1614, and officials went to extraordinary lengths to identify — and eliminate — all traces of Christianity in Japan. This post is about how the oppression of Christianity in Japan began, and why. As we’ll see, the why had very little to do with religion and more to do with politics and xenophobia.

Martyrs of Nagasaki: Sengoku Japan

First, here is some background on the political state of 16th century Japan. Although Japan still had emperors, since the late 12th century the real ruler of Japan had been the shogun, who was a military dictator. But a brutal civil war called the Ōnin War (1467-1477) destroyed the authority of the shogun. The Ōnin War marked the beginning of Sengoku, the “warring states period,” in which clans of samurai fought each other for territory and power. Civil order in Japan was nearly extinguished.

During Sengoku what civil order existed was being enforced by the samurai clans. Samurai were not just warriors but were an elite military caste that dominated Japan. The heads of the samurai families or clans were called daimyo, and a daimyo was something like the fuedal lord of his territory.

Eventually some warlords came forward to unify Japan, preferably under their control. Most notable of these was Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582). who turns up in an earlier post, “Ikkō-Ikki: Buddhism and The Japanese Peasant Revolts.” Nobunaga had not yet achieved his goal of unifying Japan when he was assasinated in 1582. Toyotomi Hideyoshi had been one of Nobunaga’s retainers and then became his successor. He continued Nobunaga’s work of unifying Japan and was successful enough that he became the de facto ruler of Japan. He did not call himself shogun, however, because he had been born into a peasant family. Instead he called himself the emperor’s regent.

Martyrs of Nagasaki: Christian Missionaries Arrive in Japan

The first Christian missionaries known to reach Japan arrived during Sengoku. Francis Xavier (1506-1552), a Jesuit priest, reached Japan in 1549. This was just six years after the arrival of the first European merchant ships. He was accompanied by a Japanese man named Anjiro, whom Xavier had met in Malaysia, and two other Jesuits. Francis Xavier tried and failed to meet the Emperor Tomohito, but he and his mission work were welcomed by Oda Nobunaga. After making a promising beginning at converting the Japanese, Father Xavier left Japan in 1551. His Jesuit brothers remained and continued the work, and eventually more than 90 other Jesuits joined them.

Nobunaga was keenly interested in reducing the power and influence of some of the Buddhist sects. In the years to come Nobundaga would ruthlessly put down a peasant revolt led by Jodo Shinshu priests and destroy Enryakuji, the most prestigious Buddhist temple/monastery complex in Japan and home to thousands of monks, who were slaughtered. Nobunaga considered the Enryakuji monks to be a threat to his power. Nobunaga probably thought that anything that challenged the authority of Buddhist clergy was a benefit to him.

With Nobunaga’s approval, the Jesuits had remarkable success converting Japanese to Christianity. These missionaries were sometimes able to convert daimyo, the elites who headed samurai clans, and all their subjects with them. It’s believed some of these conversions had more to do with the idea of gaining connections and influence with the foreigners than with religious devotion, but the missionaries considered them a win in their column nonetheless.

The Christians of Kyushu

The mission was especially successful on Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan’s main islands. One of the first daimyo to convert, in 1563, was Omura Sumitada (1533-1587), whose territory was in northwestern Kyushu. Sumitada required the people living in his territory to convert also. And in his zeal Omura Sumitada destroyed the Buddhist and Shinto temples and shrines in his territory, an act that would have many repercussions.

Someone who objected to the destruction of the temples and shrines destroyed the main seaport in northwestern Kyushu that served Sumitada’s territory. So, in 1570 Sumitada opened the port of Nagasaki to the Jesuits so they could come and go from Japan freely. Nagasaki was a small fishing village, but from that time on it grew into a center of foreign activity.

By 1584, the Jesuits had recorded more than 300,000 Japanese converts. A third of these were on Kyushu.

Oda Nobunaga was assasinated in 1582. By 1585, Toyotomi Hideyoshi had fought and maneuvered his way into Nobunaga’s place as the most powerful warlord in Japan. For a time he seemed to continue Oda Nobunaga’s benign acceptance of the Christian missionaries. But that changed.

Hideyoshi’s Persecution of Christians Begins

In 1587, after he had seized control of Kyushu, Hideyoshi issued an edict that banned missionary activities. Hideyoshi’s edict also called for expelling foreign missionaries, but this was not enforced. In Kyushu he had seen that Buddhist and Shinto shrines and temples had been destroyed, and that common people had been forced to convert to Christianity by their daimyo. He also imagined, with no evidence, that the Jesuits had sold Japanese into slavery. And he became concerned that Christian daimyo would have mixed loyalties.

After this, the Jesuits were careful to keep their heads down. The Jesuits had already adopted a policy of respect to local etiquette and culture. In short, they tried to blend in and appear less “foreign” to their hosts so that the Japanese would be more comfortable with them. They thought if they remained unobtrusive they could continue to do their work as priests.

By 1592 Hideyoshi had effectively unified Japan under his control. Then Franciscans arrived in 1593 to begin their own mission work in Japan. Believing they had Hideyoshi’s permission — they did not — they built a church and began holding traditional Latin masses, with sermons, singing, bells, and the works. They also preached in public, which Hideoyoshi had forbidden. The Jesuits — who knew Hideoyshi to be volatile — warned the Franciscans to tone it down. It didn’t help that there was rivalry between the two orders.

The Crucifixions of the Martyrs of Nagasaki

In 1596 a Spanish galleon was shipwrecked at Urado Bay, a bay of the main island of Shikoku, which is north of Kyushu. The local daimyo ordered his samurai to confiscate the cargo. According to some accounts, weapons were found on the ship. The ship’s navigator, possibly under torture, “admitted” that Spain was planning to invade Japan, as soon as the missionaries had done their work of “softening” the population with religion. When this was reported to Toyotomi Hideyoshi, he ordered the executions of the twenty-six Christians in Nagasaki.

Why these particular twenty-six people were chosen for execution, I do not know. By all accounts their executions were brutal. For several days they were torturned, mutilated, and paraded through villages throughout Japan. Then on February 5, 1597, they were crucified, tied to crosses and impaled with spears, on a hill overlooking Nagasaki.

Postscript

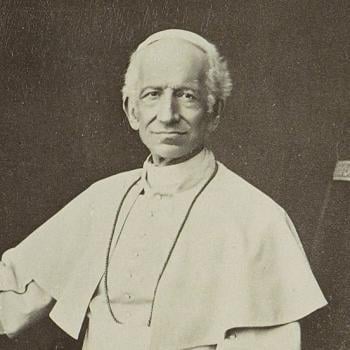

The 26 martyrs were canonized on June 8, 1862, by Pope Pius IX. They are commemorated on February 6, since February 5 already was the feast day of Saint Agatha. Francis Xavier also has been formally venerated as a saint by the Catholic church since 1622. The Basilica of the Twenty-Six Holy Martyrs of Japan, built in the late 19th century, sustained damage from the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945, but it has been restored.

A great deal more happened with Japan’s Christians in the years after the crucifixions at Nagasaki, and that will be covered in the next post.