Christianity was banned in Japan in 1614. This was about 65 years after it had been introduced to Japan. The last post told the story of the 26 Martyrs of Nagasaki, a group of Franciscan priests and Japanese Catholics who were crucified in Nagasaki in 1597. But that was just a preview. More executions followed, and after the ban Japanese officials went to extraordinary lengths to identify — and eliminate — all traces of Christianity in Japan. This purge of Christianity eventually extended to western hegemony in general, when nearly all foreigners were barred from entering Japan, and Japanese were barred from leaving it.

I mostly want to look at why this happened. I sometimes hear it said that Christianity was suppressed to protect Buddhism. But, frankly, most of the warlords originally behind the suppression of Christianity were not known to give a hoo-haw about Buddhism. At times they were as merciless toward Buddhist sects as they were to the Jesuits and Franciscans. And as told in the last post, one powerful warlord, Oda Nobunaga, encouraged the Catholic missionaries because he hoped they would take the more powerful Buddhist institutions down a few pegs. In truth, most of the leaders of 16th century Japan were less concerned with religious doctrines than they were about their own grip on power.

But now we move into the 17th century. The warlord who ordered the crufixions at Nagasaki, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, died in 1598, apparently of some disease. By 1600 control of Japan had passed to Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616). Tokugawa Ieyasu was named Shogun in 1603. (As explained in the last post, Japan did have emperors, but beginning in the late 12th century the real ruler of Japan was the Shogun, a military dictator.) Tokugawa Ieyasu and his successors — the Tokugawa shogunate — would govern Japan until 1868.

Why Christianity Was Banned in Japan

Unlike many of the other military strongmen of Japan, Tokugawa Ieyasu was said to have been genuinely devoted to the Jodo Shinshu school of Buddhism. Whether this factored into his policies toward Christianity I cannot say. What might have worried Ieyasu, however, was Christianity’s claim of exclusivity. Japan had already adopted two foreign religions, Buddhism and Confucianism. Elements of popular Daoism imported from China had also been absorbed into Japanese folk beliefs. These foreign religions had co-existed reasonably well with the indigenous Japanese animistic religion that today is called Shinto. Indeed, Shinto and Buddhism commonly shared shrines in those days. In Japan, it wasn’t unusual, especially for laypeople, to mix together practices of more than one religion. But Christianity was insisting that it had to be followed exclusively. This may have triggered the Shogun’s fears that Catholic converts would be more loyal to the Pope than to him.

(This is not to say that religion in Japan was always harmonious. Centuries earlier some of the larger Buddhist monasteries began to hire mercenaries for defense. These mercenaries usually lived in the monasteries as monks, but it wasn’t clear they were ordained. And from time to time they were sent forth to attack rival temples. These disputes were usually more about politics and patronage that doctrinal disagreements. The practice of monasteries hosting their own private armies was ended in the 16th century by the aforementioned Oda Nobunaga, in a process that involved destroying many venerable temples and slaughtering thousands of monks.)

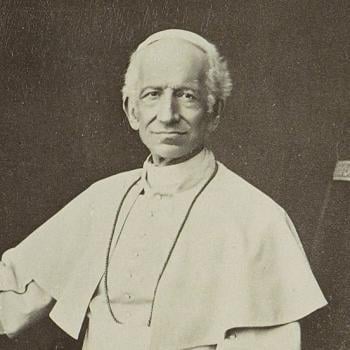

The new Shogun also suspected that the missionaries were the tip of the spear of European colonization. In the 16th century Spain had already seized the Philippines and parts of Malaysia. Portugal occupied a large part of Ceylon, today’s Sri Lanka. The established pattern was that first came merchants and missionaries, and then came warships. Was this the plan for Japan? It probably didn’t help that, in 1600, Pope Clement VIII authorized more orders to do missionary work in Japan. Dominicans and Augustinians began arriving in Japan two years later.

More Suppression

In time the concerns won out, and the Shogun banned Christianity in Japan in 1614. Waves of executions of Christians followed. Over the next few decades a few hundred missionaries and Japanese Christians are known to have been executed for being Christian. In 1629 Japanese officials began a practice called fumi-e, in which suspected Christians were required to step on an image of Jesus or Mary to prove they weren’t Christian. Those who refused were executed. Christianity was driven underground.

Remarkably, or perhaps irrationally, a few Catholic missionaries continued to arrive in Japan during this period. Two Augustinians who entered Nagasaki in 1632 were betrayed to authorities by the Chinese merchants who had given them passage on their ship. The Augustinians fled into the hills for a time but were recognized, and executed, when they reappeared in Nagasaki later that year.

The Tokugawa shogunate made use of the danka system to monitor Japan’s population. Danka originally was a long-standing custom in which households financially supported a Buddhist temple, which in turn would take care of the spiritual needs of household members. This system was voluntary, but the Tokugawas made it mandatory. All Japanese were required every year to register with the nearesst Buddhist temple to obtain a document called terauke that certified they were not Christian. One needed a terauke to function in society; to marry, to get work, to travel. The temples also kept track of births and deaths, who married or who moved away. All of this information was gathered and passed up the national organization chart, so it became a kind of running census for the shogunate as well as a means to identify hidden Christians. The system was also a major source of income for temples, which charged fees for issuing the terauke. Temples were also required to provide funerals and memorial services for all their registrants.

Sakoku: “Closed Country”

In 1637 a coalition of ronin and mostly Catholic peasants began a rebellion on Kyushu. (Kyushu is the southernmost of Japan’s main islands, and it had the largest number of Catholic converts.) The rebellion was against ruinous taxes imposed by their daimyo — a daimyo was something like a feudal lord — and also against his ruthless suppression of Christianity. The rebellion was quelled by the shogunate in 1638. The third Tokugawa shogun, Iemitsu (1604–1651), believed that European Catholics were behind the rebellion, and all Portuguese traders were evicted from Japan. And then most other foreigners were evicted from Japan, as well as mixed-race children of Japanese and foreigners.

The period called Sakoku — “closed country” — began in 1639. Japanese were no longer allowed to leave Japan. Non-Japanese were not allowed to enter, with a few carefully watched exceptions. Foreign trade was mostly limited to the Dutch East India Company and China, and these foreign merchants were allowed to set foot only on an island in Nagasaki Bay. Japan was not completely cut off from the rest of the world, but very nearly so. This isolation was finally broken in 1853, when Commodore Matthew C. Perry entered Tokyo Bay with four steam-powered and heavily armed U.S. warships and asked to speak to whoever was in charge.

In the meantime, Christianity went deep underground. A few European missionaries remained, in secret, but when they died people had no priests to lead them. Yet thousands of people, especially on Kyushu or the smaller islands near Kyushu, continued to practice Christianity in secret. They worshipped in hidden rooms in their homes. They memorized liturgies and teachings and passed them on to their children orally. And this continued until the end of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868, which also ended the ban on Christianity.

When Christianity Was Banned in Japan: Postscript

Today, according to the government of Japan, about 1.5 percent of Japanese, about 1.9 million people, are Christian. This percentage appears to have not changed for several years.

Although danka seemed like a great deal for Buddhist temples, over time it had a corrupting effect. By the end of the shogunate smaller temples in particular were nothing but funeral businesses. There also was considerable pent-up resentment against Buddhism about the danka requirement to give money to Buddhist temples whether one wanted to or not. In recent decades thousands of small temples have closed, and many of the larger, historic temples rely on tourism for income.