A bunch of people I know are defending their dissertations soon. It reminds me of mine, and mine follows me like a shadow. It was, um…different, you could say. They said it was the most-attended defense in Marquette University history. I’m sure that’s impossible to actually know, and I’ve decided that some other defense way back in the whenever had the most.

I do remember the crowded room. We had to get more chairs. The place was jammed with rows of chairs all the way up to the long table at which my board and I sat, facing the crowd. We were shoved right up against the back wall. People spilled out into the hallway.

I tried to take it in stride. I had invited anyone who cared to go, not thinking they’d care to go. All I focused on was the two librarians I had saved seats for: my two favorites, who had lifted me through everything as I worked for them during my studies. I looked at my friend, Gregorio, who had taught me poetry. Or rather, who had connived me into loving poetry, because when I arrived at Marquette, I fucking hated poetry.

So of course my dissertation featured poetry.

(Dammit, Gregorio.)

And I looked at my friend, Jeff. A scruffy Thomist. He was right in front of me. We smiled at each other. He told me I’d better not suck.

Yes.

I couldn’t look at my parents. They were already teary-eyed messes, and the damn thing hadn’t even begun. Oh, parents. (At least my sister had her act together.) I didn’t know how to interpret their tears, I really didn’t. I didn’t want to cry with them, so I didn’t look their way, and if their tears meant that they were proud of me, I understood this in a distant and almost untouched way. A glittering object at the far end of a garden.

I wasn’t okay. Underneath a relatively calm and fidgety demeanor, I was unraveling. I was in truth very, very sick. But I didn’t know, didn’t understand, had no words for it. Mental illness was not a part of my world accept as a weakness and a threat. A defeat of the worst kind. The intellectual kind.

That’s not at all what being sick means, but I couldn’t imagine otherwise. We all only know what we know.

There was much that I did not know.

And there were so many people there. I didn’t understand that, either. I thought that they were there because I’m extremely helpful, and they were sort of honoring that or something. It didn’t occur to me that they liked me. That they liked me just because I’m me. It’s not rocket science. They definitely weren’t there because everyone at Marquette is so excited about Hans Urs von Balthasar, poetry, metaphysics, and Christology. Yeah, no. Still, I can only remember feeling puzzled.

The memory follows me, the whole procession of it, because it so thoroughly pulls together everything good and everything broken in my life. Both at the same time. It was a room fit to bursting with people, a shining victory. My victory.

(Well, and Jesus’ victory. What’s up, Jesus?)

And I was a devastated human being, hollowed out by years of sexual violence that I had no strength left to ignore. I was absolutely defeated, incredibly broken. That was mine, too.

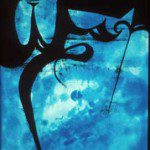

In the Gospel of John, there is this story where Jesus heals a blind man. The people in the town ask the guy if he really is that blind beggar from the street or if he’s someone else. He says simply, “I am.” (The Greek is ἐγώ εἰμι.) He is somehow both.

I cling to this story. It helps me make sense of myself.

It helps me make sense of the self I was then. The defense went extremely well. It wasn’t what some of them end up being: a test of the candidate’s mettle, a brutal passage through hell. It was more meditative, I guess, and together we reflected on the (Christological) synthesis between image and metaphysics that I had managed to draw out of Hans Urs von Balthasar. Someone in the audience told me later that it felt like a liturgy. That’s a lovely image.

I can only recall a blur of questions I don’t particularly remember, and answers that have since escaped me. I know that I spoke beautifully. I got that feeling I always get, this hook in my chest, when I know I’ve spun gold. People got that look on their faces that they do when they hear it. That unique, breathless hurt that really means how beautiful.

Balthasar – borrowing from Karl Rahner, by the way – says that when we look at Christ on the cross, we recognize his infinite love as love. We can do so because we have a Vorgriff (fore-grasp) of his infinite love for us. How else could we recognize it as love, after all, unless we already had some sense of it? At the same time, Balthasar writes, we also grasp that we do not love like Christ does. We also hurt to see how we fail to love as we could.

Earthly beauty is something like this. We know it as beauty because we are beautiful, and so are able to recognize beauty. Yet we also recognize our ugliness.

The way I speak does this to people sometimes. Yes, I think a lot of dark things about myself, but I’m aware that I’m eloquent. Human beings are creatures of mottled self-awareness: we grasp some elements of ourselves and not others, all at the same time. Don’t ask any of us to be self-consistent.

I was so shattered. I can’t explain, could probably never. I don’t know how to describe collapsing before decades of agony I didn’t have names for. And I was also so thoughtful and so well-spoken, so fucking insightful. In front of some of the people I love most in the entire world. The whole crowd of them.

That is perhaps what is hardest to make vivid in my memory: the warmth, the care, of the moment. Of the gazes set on me. That I even try to imagine it is worlds away from where I’ve been.

I try to hold on to the beauty and the ugliness of the memory. I cannot quite put them together, cannot quite see the recollected form. I think, perhaps, remembering takes practice.