My mother was about to fly to hers, fly to her mother’s deathbed, to pray the rosary at her side. My mom spoke to me more than once about this, about needing to do this for her mom. She shared her quiet worry that no one else nearer to her mother would do it. And my mom, who so very perfectly bears religious wisdom for which she has no words, could only say, “Someone needs to pray.”

She didn’t get a chance, since my grandma died only a couple days before the flight. My mother arrived to stand with her family in the quiet storm of grief rather than to sit at her mother’s side. When I learned that my grandmother had died, this was the first thing that I mourned. That my mother didn’t get a chance to pray. She did pray before in her other visits, I’m sure, but – oh – to have been able to pray one more time, or a dozen more times. Oh, to have only.

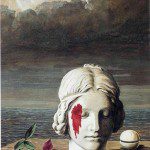

My grandmother was not exactly easy to get along with. This puts it mildly. She was severe more than soft, devastating with words, impossible to please. She was an odd paradox that has always seemed to define my mother’s family: defiant yet generous. I have rarely known a person more capable of resentment while also being irrepressibly giving. Like wearing a visible wound while carrying bandages. Like the poor woman who gave her two copper coins, which were all she had (Mk 12:41-44).

She lost a lot, my grandmother. Sometimes I think it was why it was so hard for her to be warm.

I cannot imagine what it was like to grow up with a drunken, abusive father. He hurt their mother, who is – notably – the only human being I have never, ever heard anyone in my mother’s family say a negative thing about. I cannot imagine what it was to grow up with such a loving person and a person so unable to love. The world must have felt so dangerous, and that I do understand.

She lost one of her sisters, too. Her sister slowly died from burns, leaving behind seven children and their father. My grandmother took them in, and for several years she was in charge of a small apartment filled with thirteen children. What grief she must have felt, and what a breathtaking gift to the sister she mourned. She only ever said of it, “We did what we had to do.” That she saw such things as necessary concealed the gift they are. Revealed the automatic character, the ordinariness, of her generosity.

Then she lost another sister. This one died of kidney failure from complications after giving birth. Again, my grandmother took in her sister’s two children for a few years.

My grandmother never met an opinion she wouldn’t give. Once, her hearing failing her, she walked away from a recording of my sister leading the high school musical, complaining, “Like knives in my ears.” The memory still hurts, and I am not even its subject. It is a memory that fiercely symbolizes how deeply my grandmother could inflict damage to the family she so obviously also loved.

She lost her hearing. Her favorite thing in the entire world to do was to have a conversation. It always went like this: a connection to the moment led to a connection to someone she knew, who knew someone else she knew, who knew you. Her entire world, the one she increasingly lost, was a network of people she spoke to and remembered.

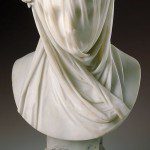

I will always remember the edges of her, the cohesion of contradictions that she was. Like broken glass in a window, the fractured pieces still leaning together along jagged lines of white, somehow refusing to lose their shape. If Jesus makes a saint of her, which I hope and trust he will, she will be the saint whose scars will be made the most beautiful marks she wears. (Same as the God who still wears his.)

My mom learned to pray through her mom, and my mother’s prayers are beautiful. Though I knew my grandmother’s Catholic religiosity as embittered, still my mother’s very existence hints at far more than my grandma knew how to say. And I think of it like that: as not knowing how to say. Even though I spent a youth fighting her negative opinions at every step, there was – and is – still the press of having-cared. Of having a care to be bitter about. A gift as perplexing and hidden as many of her gifts.

Her favorite movie was Breakfast At Tiffany’s, a movie I find at best annoying and at worst annoyingly confusing. But it is about a woman who lost a great deal and who is worthy of love anyway, and in that I also see my grandmother.

I knew my grandma best through cooking. I have a strong deferential streak, a trait that let us get along quite well, and I was most happy to defer to her in the kitchen. Being her sous chef was when I felt closest to her. We could be concrete, and work with our hands, and give something at the end. These were the words she knew.

And I loved to ask her questions as we cooked. I asked her questions when she could still hear me, even as I increasingly had to hear the timer for her. Questions about when she was young, or how she met my grandpa, or what Chicago was like. One of the most entertaining was asking about grandpa, since if he was there it almost always became a debate about who liked who less when they first met. Once she told me about how, after her first date with my grandfather, she came home to an unhappy father. My grandpa had heard the yelling, walked back up to the door, knocked, and said, “She was with me. You don’t have to worry about her when she’s with me. I’ll take good care of her.” (Holy shit, the guts of my grandfather, right? Him and his Sicilian machismo.)

My most favorite story was about their wedding. My grandmother only ever reviewed it in a series of complaints, but what kickass complaints they were: the whole neighborhood was there, they processed a cake into the hall, there was so much food. It was an old-school Sicilian wedding in Chicago. I’d ask her about it and she’d complain, and I’d dreamily imagine a wedding thick with heritage. Despite the fact that I preferred death over admitting interest in marriage.

My grandma wasn’t Sicilian, which made it an odd marriage for the time. “Dangerously” mixed and all that. She learned how to cook all the dishes, could make amazing food. And I remember how, with a single flourish, she could use her spatula to capture all the remaining batter at the bottom of a bowl. An elegant act of muscle memory. Nothing can go to waste, because there’s no money and thirteen kids. Nothing can go to waste, because we must give what we have. No matter how broken.

As we look ahead to her funeral – we all have to return to Chicago, and the massive act of gathering the family will take three weeks – I worry most about my mom. This is her mother, and she loved her in the only way she knows how: tenderly. With a heart that wants to pray. For all my grandmother’s hardness sometimes, she gave me my mom, and my mom is soft. She gives her heart to people, and she learned giving from her mom. The mom who lost so much, whom she now loses.

Loses to the God who answers every prayer, which means he still listens to my mother’s prayers for her mom. And my mom can still pray them, can always pray them. Such is the God who also prayed. The God who also has a mom.