What’s it mean for someone with a damaged mind to stand before God? How do the mentally ill pray? I ask myself this question in quiet ways, since the question itself stills me with sharp pain. A needle through the skin.

I do pray. I also, to borrow from C.S. Lewis, “practice the absence of God.”

If we cannot “practise the presence of God,” it is something to practise the absence of God, to become increasingly aware of our unawareness till we feel like men who should stand beside a great cataract and hear no noise, or like a man in a story who looks in a mirror and finds no face there, or a man in a dream who stretches out his hand to visible objects and gets no sensation of touch. (The Four Loves)

I am greatly wounded, and sometimes I comfort myself with the knowledge that God has made new things out of worse. At no point do I imagine that my spirituality will be what it was. How could it possibly? Those were the prayers of one who had not tried to die. But I have no real idea what the new prayers will look like. If the present is any indication: uncertain and pained.

Sometimes I think about the infinite capacities of the human mind (mens) and spirit (spiritus). I imagine my wounded mind constricting my capacity for God, choking everything spiritual in me. I choke not really because of sin – though there’s that too – but because of things I didn’t do at all. An illness I never earned. I feel terrible sadness at this, and often fierce anger. I do not trust God, and I’m quite aware that my distrust is a confused knot of trauma and the spiritual.

We cannot be Descartes anymore, especially after helplessly enduring mental illness. I am not entirely the master of my own mind.

This is some kind of mediatory suffering. The breakdown of a partial bridge between the physical and the spiritual self. It is the place where all dualisms die. That the mind can break this way at all speaks of a reality that usually works another. Some kind of effective bridge. I am not, after all, body and mind. Not quite. I am (an) embodied mind. To try it another way: Thomas Aquinas says that the soul is the form of the body. This means that the two intimately exist with one another, all while not being the same.

I know that people hate epistemology and such, but I’m talking about mental illness and my damn mind. I’m trying to figure out what it means to be a spiritual creature who can be mentally ill.

And I don’t really know. Especially once I strip away the armor of a scholar and try to pray. I am so helpless to prevent certain reactions, and still so very aware that there is more. Ritual, for example, is as much trigger to me as door. I find this fact in particular endlessly frustrating, even lonely. I want to be able to relax at Mass. Someday, I tell myself. Someday. God has made something new of worse.

Or, you know. He hates me and wants me to hurt. Depends on where you catch me, hinges on the moment and where I am in my head. Or however it works. I sincerely believe that God loves me. I also sincerely think he doesn’t. That’s me: somehow always almost safe and never again safe. Always living along that God damn partial bridge of body and mind.

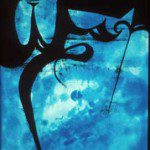

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about the crown of thorns, especially in the form of the statue pictured above. I think of Mary meeting her Son on the way to the cross, touching the wreathe that hurts. (Or that’s actually Veronica, but don’t ruin my day.) What a painful and perfect symbol: the mind, the golden crown and highest capacity of every human being, twisted into thorns. Alongside Mary’s shelter, touch, and worried gaze.

It’s strangely comforting to imagine. I’m not just the snarling possessed, the twitching demoniac who rasps Jesus’ name. If the crown of thorns is my symbol, then I am something more.