I don’t much like explaining why I am a Catholic. As if I made some kind of decision at some point, specific and clear, and could then describe that moment and its reasons to others. As if that’s how it works. And of course it doesn’t work that way, but this doesn’t mean I never made a choice or never had reasons.

I am a cradle Catholic, which means that I have had the privilege and problem of growing into a faith that was already mine. Faith was given to me the moment I was born, because they feared I might die, and so I have spent life within faith almost every second that I have breathed air. So faith is very much like air to me, fundamental and automatic, invisible and taken for granted.

Painful when it goes missing.

The sacrament of Confirmation was not when I became a Catholic on my own. That is not what Confirmation is for, not even remotely. Confirmation is not the driver’s license of the Church. I’m not even sure that Catholicism is ever had on your own. Lonely shoulders couldn’t bear the weight of two thousand years and the immensity of the cross. Or at least, mine definitely could not and cannot.

Thousands of decisions lead to one another, thread-like and delicate, in the contours of a faith stretched across a life. Thousands of reasons rest upon one another, both known and forgotten, the paradoxical crossbeams of a faith seeking understanding in time. There is no summarizing it except to say that what I am, including all its contradictions, has been lived under the burden and freedom of faith. And if faith does not appear as burden and freedom at turns, well. Faith will. It will. Or else it is faith had on your own.

Which cannot last lonely under the weight.

Recently, a young woman that I know asked me why I am Catholic. I smiled at her, soft. There is no explaining, but we will never stop trying, or asking others in order to ask ourselves. I confessed that I was once an atheist. Secretly. I told no one that I had figured out that there was no God. I was a teenager, and my atheism lived in me sadly, devastated by the impossibility of faith. It was not so much that faith was happier, or a consolation, and now I was sad not to have it. Part of my struggle was that faith is not these. More poignantly in my young mind, the unreality of faith destroyed a certain kind of creativity. An inventive, breathless thing. My world became much smaller, though it still included galaxies.

Then I came to a point at which I merely surrendered to faith. I realized that surrender was a possibility. I’m not sure that I had reasons, not specific ones, but I wasn’t blind. I had un-learned the faith that imagines anything is easy. Perhaps my rejection of God was a way of mourning and enduring this.

But even here the memory shifts to meet me as I am. I’d have used different words for it back then. My reasons and decisions have had years to grow from and away (and with) these old ones.

At one point during my graduate work, I think near the end – when all existential crises occur – I wondered what on earth I was doing. Wondered what I was doing with Catholicism, of all things. It’s not like it’s easy to be one. It’s not like it’s always self-evident. And again the old chasm loomed before me: the long leap between Catholicism and atheism. Somehow my heart knows no in-between. I’d be a Catholic atheist like Eugene O’Neill. Perhaps have been sometimes. (And still my baptism marks me.)

I was reading through the documents of the Second Vatican Council. I have no idea why. There was Lumen Gentium, “Light of the People/Nations,” which is what the Church has to say about itself.

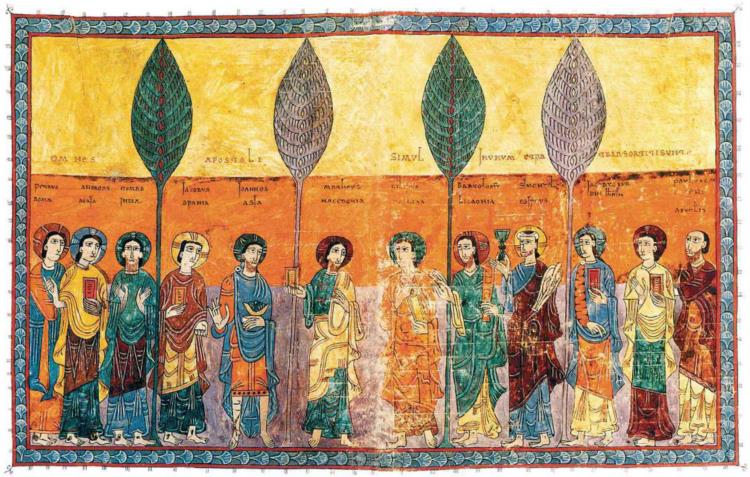

One of my professors had taught me that the light (lumen) is not the Church – it’s Christ. That’s the first sentence of the document: “Christ is the light of nations” (1). So in its very first act of thinking about itself, the Church does not think about itself. It looks upon Christ. (For faith is not had on one’s own.) The measure is at once an act of deference, a deep bow to the only reason the Church is anything at all, and at the same time a description of the Church as deference. Christ is “a light visible upon the countenance of the Church” (ibid), and the Church is the one who looks upon – not the one who is.

That is very, very old theology. Arguably from Saint Paul, and certainly dependent upon Johannine literature.

Lumen Gentium, that document from that council, does something even stranger still. There is this line:

This is the one Church of Christ which in the Creed is professed as one, holy, catholic and apostolic… This Church constituted and organized in the world as a society, subsists in the Catholic Church, which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the Bishops in communion with him, although many elements of sanctification and of truth are found outside of its visible structure. (8, emphasis mine)

Great, the Catholic Church is making a grand statement. We’re famous for that. We’re famous for our absolutism, for our claims of absolute truth, and this habit is often derided as stubborn arrogance. Here, it looks as if the Catholic Church is doing that thing again, pointing at itself and saying extra ecclesia nulla salus est (outside the Church there is no salvation). Congrats on being predictable.

What is happening here is much more than that. While the old absolute statement is never denied, while the Church is still one and still Christ’s, we suddenly see the Catholic Church saying that this one Church “subsists in” (subsistit in) the Catholic Church. What does that strange phrase mean? Theologians have argued bitterly ever since. This we do know: “subsists in” is not is, and it is not isn’t. The one Church of Christ is the Catholic Church? No. The one Church of Christ isn’t the Catholic Church? Also no. The Catholic Church has somehow found a way to say something else, something “between,” while refusing to compromise.

The strangest thing, at least to my eyes, is that this is a tradition that has found a way to relativize itself. It relativizes itself not only with respect to Christ himself, but also with respect to its own countenance. Traditions do not normally self-relativize. They do not ordinarily re-orient themselves before a greater mystery, and they do not go and admit that they cannot entirely comprehend the very reality that they hand down.

How do I explain it? If I am myself – if I am me – then I’m the one who knows me best, and I’m the one who explains me best. (At least by action.) What the hell would it mean to say, “I am not quite me, and I am myself?” Who the hell else am I? And where the hell is the real me? But this is what the Catholic tradition has done in a far more complex way. This is the resplendent act of an iron tradition revealing itself not to have been iron at all. (Not iron, but gold, tested in fire.) This is the astonishing moment that something universal – meant for everyone – acknowledges that there is still one greater than even itself.

The tradition is not so universal. It just knows who is. And the tradition surrenders to him.

And so I read those words, subsistit in. I saw the strange moment, the astounding action, the self-relativizing tradition. That’s the only thing that can really be universal, isn’t it? And I wanted to be a part of it.

The reasons don’t say everything, and they never will. But these are some.