I think I died that day. I didn’t die, not really – but I did. I did die. In some unfathomable way, I died that day as much as I lived. Everything went away and I came back again: alive and dead, dead and alive. If there is anything I know, it is that there will be no real making sense of it.

The day I dragged a knife across my throat and did not die. The day that I did die – and lived.

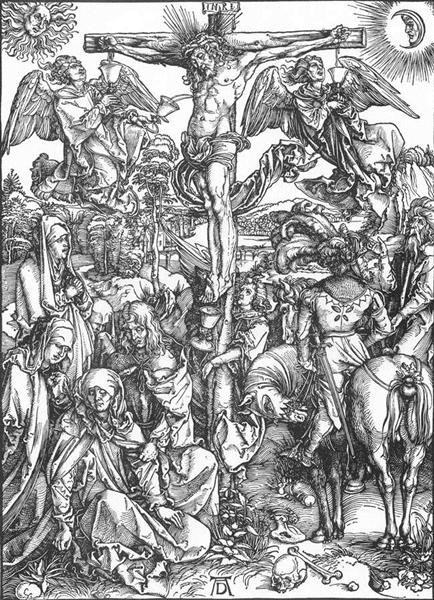

I’m not sure I’d call it a resurrection. I think that God did not want me dead, and so I did not die. Nothing happens that God does not allow. Not the knife, and not the not-resurrection.

Coming back to life takes longer than you’d think. Longer than I ever thought it would, if I ever thought about it, which I did not. I was unable to any longer think past the present hour. But I know the hours (some of the hours) that led up to that one, and I know the hours (the many hours) that expanded out beyond it. Out and away, like the breath I released that was not my last.

I was born much, much too early. I almost died then, would have died then, except for a hundred thousand things including the fact that God did not want me dead. My mom says that I used to forget to breathe. I can picture myself in her hands, very small and covered in wires. I’ve seen the photos, and I’ve seen my mother’s eyes.

I was a sickly child. I was not supposed to walk, to speak. These I did. I endured things for which I have no name. I went to high school, but was too sick for much of it. Pain was as familiar to me as my own breath. Sometimes simultaneous.

When I tell the story like this, it is not any surprise. What happens later. But it is surprising, and was surprising, and will always be surprising. I know what it is like to walk with a cane, and that is hard, but that doesn’t mean I figured there would be a day (and days and days) when I did not want to – did not want to anything. I can tilt my head and tell the story as if it makes sense; I can turn another way and name its non-sense.

So suffice it to say that I know what suffering is. Most human beings do. I have spent most of my life being associated with suffering, from my birth to my limping gait to my stomach that never doesn’t hurt. (That doesn’t mean I ever figured there’d be a day…)

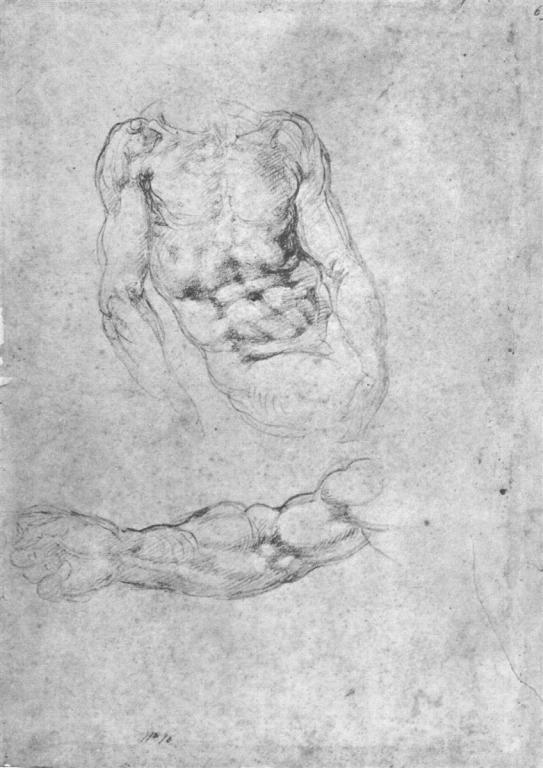

Looked at the one way, I am a frail creature who has somehow survived more than one thing. Looked at the other, some kind of iron cord of grace in me has always refused to snap.

Under the moonlight, in the cool and shadow, there is this other way. Simultaneous in its being, and incomprehensible in its imagining: I did not die, because I fought to live, and God granted it. I learned compassion, and learned the quiet shades of expression that can sweep across a face. And bravely, tremulously, I fucking survived.

Like glass I shattered, and still I did not die. I don’t think I learned any secret to life, and I cannot say that any of it has made me a better person. Perhaps it made me worse. I cannot say, because I do not know the self I might have been. I know only the self that survived, the self that looks back at me in the mirror. This is the self that God somehow gave as a grace to me, with the mysterious complicity of my own will.

The other side of frailty is resilience. We hate it, perhaps, because the sick and the dying and the poor make our actual helplessness obvious. (The things we see in the silent mirror of another person.) I can say that I am strong inasmuch as I have also been weak. I can say that I am strong inasmuch as it wasn’t me at all, but was rather God’s indomitable will.

There is a mystery in there, somewhere. That nothing happens that God does not allow, and that things happen that God does not will. I cannot say that I was resurrected, but I can say that God wills me to be. I cannot say what suffering is, and I cannot say what I am, except that God allows it and that God also wills me to be. Whatever frailty God allows, there is the shadow of the time that God gives as pure gift. Even if I myself cannot always see it.

”All suffering is the same,” says Henri de Lubac in Paradoxes, “and all suffering is unique.”

—-

The title is taken from the first chapter of the second book of Gregory the Great’s Dialogues, which recounts Saint Benedict’s life.