This review by a guest contributor goes into details that are spoilers for the trilogy of movies “Unbreakable”, “Split”, and “Glass”, so consider this your SPOILER ALERT!

The Story Thus Far, True Believers…

The quiet yet brilliant 2000 film Unbreakable was released in a cinematic time long before the grandeur of Avengers movies and the depth of Black Panther. Beautifully acted, it offered moviegoers a truly wonderful superhero film experience all wrapped about a very real family drama.

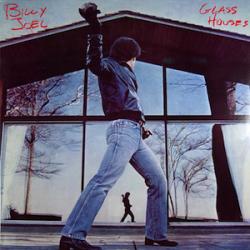

We meet David Dunn (sounds like Clark Kent, Reed Richards, Sue Storm, Peter Parker, Bruce Banner,Wade Wilson–get it?), a miraculous survivor to a horrific train wreck. Dunn (played by Bruce Willis) works in obscurity as an American “every man.” Together with son Joseph (played in both Unbreakable and Glass by Spencer Treat Clark), security guard Dunn meets the brilliant and crazed Elijah Price (Samuel L. Jackson), a superhuman intellect trapped in a body wracked with torturous pangs from birth (Price suffers from ostrogenesis imperfecta or “brittle bone disease”—a rare biomedical disorder causing the bones to shatter like glass at the slightest impact, hence his nickname “Mister Glass” given him as a child by mocking classmates). Price considers himself the living embodiment of human frailty and that since he exists in this extreme way, so also must his opposite exist. Price is the owner of an art gallery and obsessed with comic book super beings whom he considers to have basis in real historical persons and happenings.

Price offers Dunn wisdom and purpose concerning the extraordinary qualities the latter possesses but has not yet begun to taste. It turns out that Dunn has never experienced the common cold or hurt from even a broken toe. He is gifted with super strength and extrasensory vision (when touching others, their darkest secrets somehow become disclosed to Dunn). Price, explaining these extraordinary things to Dunn, informs him that like the comic book Superman, Dunn has his own Kryptonite or Achilles’ heel—common water!—Dunn almost drowned as a child, imprinting him with his sole weakness.

The story of Unbreakable progresses with the reluctant Dunn arriving at the self-discovery that he is, indeed, gifted with these incredible superpowers. He uses them to save from certain death two captive children from the murderer of their parents and becomes a real-life superhero. Many other things happen in the film, but the end is of note: shaking the hand of Elijah Price reveals to Dunn that the comic theorist is actually a real-life supervillain, a mastermind responsible for the deaths of hundreds of people including everyone in the fateful train accident where only Dunn survived.

The movie resolves with Dunn reporting the villainous “Mister Glass” to authorities who is subsequently arrested, convicted of mass murder and acts of terrorism, and placed in a psychiatric hospital for the criminally insane. The well-acted film ends relying on itself as a quiet story without FX bonanzas of energy volcanoes shooting up piercing the sky. Dunn and family live happily ever after, or so it seems…

Enter Split—

Kevin Wendell Crumb (James McAvoy) is a disturbed victim of brutal psychological and physical child abuse. As a result, he suffers from Dissociative Identity Disorder and has twenty-three other distinct personalities—all together, they come to be known as “the Horde.” As these personalities manifest “in the light” (come to in the present reality), a dramatic physiological change occurs in Crumb. Although he is receiving therapy from psychologist Dr. Karen Fletcher (Betty Buckley), unbeknownst to her a dominant personality called “Dennis” has recently abducted three teenage girls returning from a party and is holding them captive in a labyrinth beneath the Philadelphia Zoo. They are to be sacrificed to a mysterious entity of superhuman strength known as “the Beast.” One of the three kidnapped girls is Casey Cooke (Anya Taylor-Joy), also the victim of child abuse, repeatedly molested by her paternal uncle and legal guardian, John (Brad William Henke). She is a cutter and her wrists are marked with faded scaring.

In the course of Split, Dr. Fletcher, and the two captive teens, Claire (Haley Lu Richardson) and Marcia (Jessica Sula) get murdered by “the Beast,” the horrifically violent 24th personality. But wise beyond her years. Cooke outwits “the Horde” learning how to jumble them up by saying aloud “Kevin Wendell Crumb!”—the full name of the disturbed host to all these personalities. Many harrowing things happen and ultimately facing the superhuman and bulletproof “Beast,” Cooke is spared when it sees her scars, deems her purified by her suffering and she escapes.

The movie ends with “the Horde” desiring the world to see its collective power made manifest as well as a scene taking place at a diner that is a classic Shyamalan twist that ties together Split with David Dunn from Unbreakable.

Just weeks after Split ends, the story of Glass begins…

The Third Film: Glass

Glass is the film to be reviewed and it stands as a broken mess of all promises but little delivery when compared with the preceding two movies. Most of the ordeal involves Dunn, Crumb, and Price imprisoned in a mental hospital—characters whom we have come to know as truly superhuman beings—subjected to the manipulations of a psychiatrist attempting to convince them to doubt who they are and accept that being “something out of a comic book” is clearly delusional.

Dr. Ellie Staple (Sarah Paulson) is trying her damnedest to convince our heroes (?) as the head doctor of the mental institution where all three men are imprisoned. She is a psychiatrist specializing in a very particular delusion: the belief that one is a superhero. Of course there is far more than meets the eye with the good Doctor, but telling what that is would be spoiling things (saying that much is not a spoiler for anyone who has watched even only two M. Night Shyamalan films, the master of the “twist.”).

Whereas Unbreakable and Split are messy in the most glorious of human ways, Glass is messy in a disappointing film-making tenure. Unimpressive and terrible exposition and dialogue clutters it. Its frenzied pacing and tone come across jarringly different from the previous entries in this trilogy.

Despite the director’s talent for storytelling, the plot and direction seem scatterbrained. Shyamalan seems more interested in giving us his masters course on what comic book movies are really about—but what exactly new does he have to enlighten his viewers about superheroes that they have not already received (and far more handsomely) from the likes of Christopher Nolan, Sam Raimi, Guillermo del Toro, Jon Favreau, Joe Johnston, Joss Whedon, and too many others to count?

Meandering and monotonous, the middle portion of Glass spends far too much time on what Shyamalan apparently considers a fascinating mindbender: what if what we all saw in Unbreakable and Split were just the hallucinatory POV’s of delusional men? But we viewers know that there was not only one subjective view in Unbreakable (Dunn’s, his son’s, or Price’s), and the vantage of Split was that of a kidnap victim and protagonist, Cassey Cooke. So to accomplish that narratively would be too much—we’ve seen these films, experienced their yarns and tasted in them something too strong to allow Doctor Staple’s “therapeutic” machinations to bite us. The whole middle section of Glass becomes ponderous and goes nowhere. The sterile and clinical setting of the mental hospital does not help this.

Glass cuts and stabs. The film cheapens what came before and does violence to better movies. The dramatic Unbreakable was a terrific film, perhaps Shyamalan’s best, but now seems tainted and stained by the cheaper Glass. Split was an edge-of-your-seat suspense thriller, but its ending, initially exciting to many (like this reviewer), makes the whole of it a longwinded trailer for Glass. These earlier movies had deeper things to say and took their time in expressing them artistically.

Wonders that change the world in extraordinary ways for the good can be found in the simple and mundane and unexpected—Unbreakable shows, among many good things, that the love and awe of a child can find a superhero in his or her parent. Split also shows, without romanticizing trauma (and definitely not abuse!), that nevertheless such experiences can grant human beings deeper insights into suffering and even the opportunity for empathy that can help heal the world. Those aren’t bad ideas.

What exactly does Glass disclose? Is it that human marvels exist out there in the world waiting to be discovered? Or is it that we human individuals need to realize our uniqueness and potential as persons—and if that is the message, we do not need Mr. Shaymalan to preach this to us United States people, because it can be found EVERYWHERE celebrated and enshrined in our American society, the most individualistic culture on the history of planet Earth! Or could the marvelous truth of Glass be just that strange, bizarre, and unexplainable things happened at a mental hospital and the whole world needs to know? The thrust of the two previous films gets cheaply sideswiped into the gutter in Glass, drowned in a shallow puddle in its cheaply planned, blocked, and filmed parking lot fight scene climax.

The Film We Needed?

Superhero fatigue is often discussed by moguls, critics, and filmmakers as a possible danger to the film industry if not a reality already arrived at. So much has happened since 2000 when Unbreakable premiered. The Marvel Cinematic Universe was not even a pipedream back then! The greatest of the superhero films in the days of Y2K (flicks that whimper compared to The Dark Knight Trilogy, Avengers, Captain America: Winter Soldier) were shelved at your local Blockbuster video—a handful of 1980s Superman films, each sequel diminishing from the previous production and rooted in a very imperfect first film, along with a Batman franchise bearing the same pattern. Indeed, Joel Schumacher’s debacle Batman and Robin had almost aborted the then gestating Superhero Boom. The 1990s also showcased a Blade movie franchise and Bryan Singer’s X-Men which had just gotten off the ground flying when the marvelous Unbreakable was released.

What a different world 2019 into which Glass comes! Disney’s MCU, with its Iron Man, Thor, Black Panther, Captain Marvel, Guardians of the Galaxy, Captain America, and Avengers franchises, dominates merchandise and film. Although Warner Brothers has struggled with some of its DC properties, its Harry Potter extended universe of characters and adventures seems deathless and on Warners’ HBO Game of Thrones rules cable television–all indebted to write and Marvel-god Stan Lee.

Sadly, Glass is not the meal we need in this saccharine expanse of entertainment options. Both at home and at the movie complex, I eat a good portion of lava cake. There is something to be said for good lava cake! But whether it’s poorly baked or excellently prepared lava cake, nutritionally speaking, we human beings do need more than just lava cake. Glass is less than edible lava cake pretending to be côte de boeuf! It does not grow or deepen the superhero genre or the viewer. Despite having some brilliant ideas and moments (most of these taken from its predecessors), Glass fails to give satisfying completion to either Unbreakable or Split. Perhaps the worst thing that can be said of Glass is that it really isn’t an outright terrible film, but rather just nowhere good enough to proceed from the trilogy’s previous wonderful installments.

Watching all three films, one might be reminded of The Godfather Trilogy’s final installment. The III film is an admirable entry from 1990—it’s just terribly poor in comparison to the cinematic masterpieces that are the first two Godfathers. It could have been—should have been!—so much more, but wasn’t–this makes it an even greater disappointment and a disastrously terrible film. Likewise, Glass tumbles and breaks in the juggling act of its director.

Image source: https://www.pexels.com/photo/cracked-glass-mirror-762558/