Göbekli Tepe is one of the most enigmatic archaeological sites discovered in recent years. Located about 12 km from Şanlıurfa in Turkey, this large archaeological complex is now believed to be home to the world’s oldest megaliths. While locals had been aware of the ruins on top of ‘Pot Belly Hill’- as it is known in the area, it was not excavated until 1995. Previous research, such as the work done by Peter Benedict, had supposed the site to be the ruins of a Benedictine cemetery and therefore did not warrant further investigation. In 1994, however, Klaus Schmidt came to the site after a local farmer contacted authorities after running into one of the now-famous T-shaped pillars with his plow. Schmidt discovered a 5.5 meter crystalline limestone pillar with parallel nodes at the top jutting out on two sides beneath the dirt. Schmidt quickly realized that there was much more to the site than met the eye and gained permission to launch a full-scale excavation. Since then, the site has remained under almost continual excavation and Schmidt remained head archaeologist until his death in 2014. Observations made since 1994 by Schmidt and his team points towards the compelling conclusion asserted by Schmidt that Göbekli Tepe may be the world’s oldest temple. Evidence for this deduction is based on several factors; the monumental age (12,000 yrs BP) and size of the site, the indicators of ritual use inferred from the artifacts and location, the detailed carved motifs found on the stonework, the intentional burying almost 1,000 years after it was built, and the seeming lack of habitational structures.

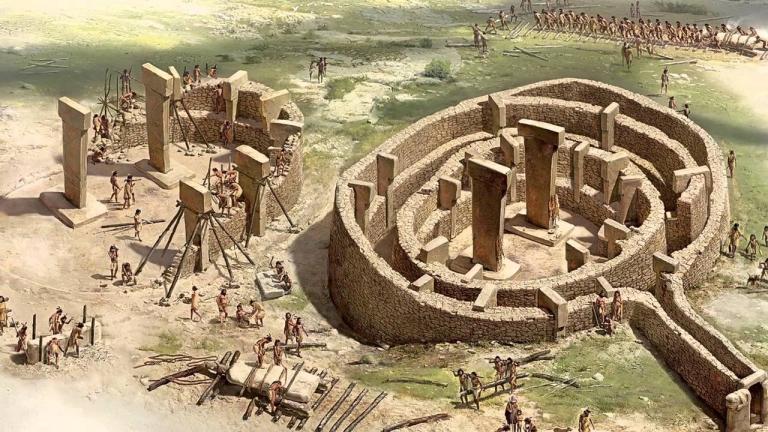

Since initial research began at the site in 1994, over 20 unique ‘henge-like’ structures have been identified, though to date only 6 have been excavated. They are known as henges due to their physical resemblance to the prehistoric stone circle at Stonehenge, England as well as their prominence in the landscape, which is a common component of neolithic monuments . The ‘henges’ consist of large curvilinear and smaller rectangular complexes with T-shape megaliths in the middle. Due to the sites location on top of the highest plateau of an extended mountain range (760m) it would have been visible from quite a distance when it was first constructed. Three distinct stratigraphic layers marking periods of Neolithic use have been established as well. Layer I marks the oldest layer (10,000-9,000 BC) and contains the curvilinear henges with the T-shaped pillars, these pillars average at 3.5 m in height and weigh up to 10 tons. Each of the six excavated enclosures in this layer is encircled by 10-12 stone pillars and is approximately 10-20 meters in diameter. In the middle of these circles are always found two parallel T-shaped pillars. Layer II (9,000 BC-8,000 BC) contains smaller rectangular complexes but which continue to have the T-shaped pillars in the middle of the enclosures. The average height of the pillars in Layer II is 1.5 meters Layer III is the uppermost of the three and accounts for the longest period of time. It was in this layer that the earlier two layers were intentionally backfilled sometime around 8000 BC, the evidence for this will be presented later on. Layer I has been the most intensively studied and excavated. The four largest structures researched in this layer have been designated A, B, C, and D according to their order of excavation. Circle D has been the subject of the most publicity and contains the structures that have been the most photographed and circulated.

Dating at the site has proven to be difficult for several reasons. Firstly, one of the most trusted archaeological dating techniques, Carbon-14 isotope dating, can only be done on organic matter, which has not preserved at the site, thus making it impossible to carbon date the stone work itself. Dating has been done on the bone fragments found at the site, but since it was clearly backfilled in at a later date in time this is not to be confused with dates for the time of construction. Therefore, Schmidt has relied on stylistic stone tool comparisons for data on the timing of construction and use. He has used nearby sites with similar stone tools to estimate that Layer I is approximately 11,000-12,000 years BP. This is an astonishing date range for the construction of monumental architecture considering that this time period in Southwest Asia coincides with the beginning of agriculture, which until now has been theorized to have occured in conjunction with permanent settlements and later on: chiefdoms, monuments, metallurgy, animal husbandry, and the rise of the first cities.

Schmidt postulates that Göbekli Tepe was built by semi-sedentary hunter-gatherers who had no permanent settlement on site but may lived somewhere in the region. If this were the case, it would force archaeologists to rethink long-held beliefs about the birth of agriculture and society. All current prevailing theories state that agriculture is what led to the establishment of complex societal structure- one aspect of which is monumental architecture, like is found at Göbekli Tepe. Schmidt’s theory promotes an alternate hypothesis, that the ‘need’ for agriculture (i.e. surplus food) rose from large groups who had gathered to build and worship at large religious structures. He bases this supposition on three main points; the first being that Göbekli Tepe was apparently built exclusively for religious use (i.e. no indication of habitation), secondly that the site was visited consistently over a long period of time, and lastly, that the people who built the site were still hunter-gatherers, not agriculturalists.

There are several reasons why Schmidt believes the site to be religious in nature. The first, is based on location. Due to its prominence on top of the hill, it would have been easily seen from a distance. This would have been an important factor if people were travelling from far away to visit it. Schmidt believes this was the case based on the fact that obsidian from three separate locations in Turkey have been found at Göbekli Tepe, yet the area itself has no obsidian. Furthermore, the buildings on site appear to have been open-air, meaning they apparently had no roofs. E.B. Banning who believes, in contradiction to most, that the structures were large scale-dwellings has suggested that perhaps there were roofs made of reeds or other materials that would not leave anything behind, but to date, no evidence (such as pollen) has been found to suggest this.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the site, is that Layer II(9,000-8,000 BP) and

Layer I (12,000-9,000 BP) were intentionally and rapidly buried about 1,000 years after they were built. Schmidt is positive that this was the case because the soil that was found covering the structures was able to be carbon-dated (8880 ± 60 BP) using the abundant animal remains that were found mixed into the dirt. This layer has been called Layer III. Furthermore,the pillars in structure C of Layer I appear to have been intentionally mutilated. There is evidence of a large pit being dug in the center of the circle so that the pillars could be pushed over and smashed into several pieces. Ultimately, it has been a blessing to the excavators as this ensured an incredible level of preservation.The motivation behind such an act, however, remains a mystery. Of note in regards to this question, is the practice of ritual burial and/or destruction of sacred objects. This practice is found all over world, from prehistory to the present. Archaeologists may never identify the people responsible for the burial, but the questions that remain about the motivation behind such an act offer several very interesting possibilities. Where they descendants of the builders? Were they conquerors? Or were they perhaps a group who had stumbled upon the site and destroyed it based on their own beliefs? We will most likely never know for sure.

The layout, design, and decoration of the structures is perhaps the most telling sign that they were built for religious use and not for habitation. As previously mentioned, evidence suggests that they are open air, similar to what is found at Stonehenge and Avebury- although the latter are much later in time. This gives credence to Schmidt’s theory that they were open-air temples as, without a roof, they can’t conceivably have been used for shelter or storage and would have been open to the sky. The design of the henges are also a clue, the henges from Layer I are circular and contain two parallel T-pillars in the middle. This would seem to focus of attention into the middle of the henge or the sky, perhaps for ritual use.

Excavation by Schmidt revealed that the pillars in Circle A,B,C,and D of Layer I have anthropomorphic carvings on them as well as animal reliefs. What’s most curious about the animal carvings is that they almost all represent some kind of powerful, predatory animal such as scorpions, spiders, wild boar, foxes, leopards, and snakes (the latter are the most abundant). Schmidt and Peters postulate that perhaps these animal representations ‘acted’ as guardians or ‘totems’ for the site. We know from modern-day ethnographies of various indigenous hunter-gatherer tribes that animals are very symbolic and important to their religious practices, such as the Haida of the Pacific Northwest who carve animals on Totem Poles as symbolic representations of their clans and ancestors.

Another indicator of probable religious use at Göbekli Tepe is the sheer size of the complex. Construction of the henges in both Layer I and Layer II would have been a massive undertaking and would most certainly have required large-scale coordination and a community effort. Considering that this was most likely done by hunter-gatherers, as we will see later, this is a good indicator that the site was special. Contemporary sites from the same region, such as Nevali Ҫori and Çatalhöyük, have clear stone-constructed residential dwellings and specialized working areas.And while they are impressive for their age (10,000 BP), these sites simply don’t have the same degree of complexity and scale as is found at the site layout of Göbekli Tepe. In Schmidt’s opinion, this indicates that this was a regional cult center that was separated spatially from any inhabited areas.

Although food remains (animal bones) have been found on site, such as in the debris of Layer III, no hearths or other evidence of onsite food processing has been found, which would most certainly be the case if the site had been inhabited on any permanent level. Furthermore, no nearby water source has yet been found. Since water is a basic resource needed for everyday living, this is a significant indicator that the site was not inhabited. However due to the large number of food remains recovered (total bone fragments recovered from the 1996-2001 excavations were 38,704), it is commonly believed that food consumption was taking place. This has lead Schmidt and other researchers to think that large scale feasting may have taken place in conjunction with religious ritual or ceremony. Furthermore, the faunal remains found were from animals that were not domesticated such as wild aurochs, wild boar, leopards, wild cats, foxes, wolves, and gazelles. These faunal remains are of the utmost importance for Schmidt’s most revolutionary belief about Göbekli Tepe, that it was built by still mobile hunter-gatherers.

Modern archaeological theory about the neolithic revolution indicates that agriculture was what instigated the rise of civilization. Before this time, there was no ‘need’ for large scale buildings and complexes.In stark contrast to this, Schmidt thinks that ritual complexes, like Göbekli Tepe, came first. His main evidence for this idea is the lack of domesticated floral and faunal remains found on site and no evidence (yet) for permanent habitation. Modern archaeological techniques, such as pollen dating and animal bone isotope analysis, allows researchers to tell whether or not an animal or plant had been domesticated. All current analysis at Göbekli Tepe leads to the conclusion that that animals and plants consumed on site were not yet domesticated.”

As we have seen, for its age Göbekli Tepe is truly a remarkable site. Several pieces of evidence indicate that it was communally built as a religious complex and the main excavator, Klaus Schmidt, has gone so far as to call it the world’s first temple. Even more astonishing is the fact that there is significant reason to believe that it was built by still mobile hunter-gatherers. This is contrary to previous theories about the evolution of civilization which hold that agriculture came before any large scale permanent structures and means that archaeologists and anthropologists need to reexamine long-held beliefs and ideas and early agriculture in light of such evidence.

Works Cited:

Banning, E.B “So Fair a House: Göbekli Tepe and the Identification of Temples in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of the Near East,” Current Anthropology, 52, No. 5 (2011): 620-621.

Curry, A. “Göbekli Tepe: the World’s First Temple?” Smithsonian Magazine, November (2008). Accessed 4/20/18.

Curry, A. “Seeking the Roots of Ritual,” Science, Vol. 319, no. 5861,(2008):278.

Dietrich, O. Heun, M. Notroff, J. Schmidt, K & Zarnkow, M. “The Role of Cult and Feasting in the Emergence of Neolithic Communities: New Evidence from Göbekli Tepe, South-Eastern Turkey,”Antiquity, 86, 333 (2012):691.

Driessen, J. Destruction: Archaeological, Philological and Historical Perspectives, (Presses universitaires de Louvain, 2013): 121.

Fagan, B and Durrani, N. World Prehistory: A Brief Introduction 9th ed. (Routledge Press, New York, 2017):150.

Kornienko, T. “Notes on the Cult Buildings of Northern Mesopotamia in the Aceramic Neolithic Period,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 68, no. 2 (2009): 89.

Murdock, G. “Kinship and Social Behavior among the Haida.” American Anthropologist, New Series, 36, no. 3 (1934): 355-85.

Peters, J and Schmidt, K. “Animals in the Symbolic World of Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, South-Eastern Turkey: A Preliminary Assessment,”Anthropozoologica, 39 (1), (2004): 207.

Sagona, C. The Archaeology of Malta, (Cambridge University Press. New York, 2015): 47.

Schmidt, K. “Göbekli Tepe-Enclosure C,” Neo-Lithics, 2/08, (2008):27.

Schmidt, K. “Göbekli Tepe—The Stone Age Sanctuaries: New Results of Ongoing Excavations With a Special Focus on Sculptures and High Reliefs,” Documenta Praehistorica, XXXVII (2010):240.