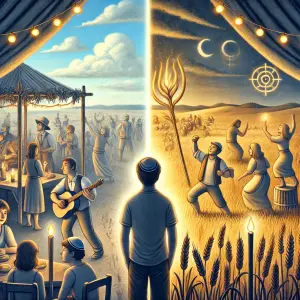

What do you do when you have to go to a party, but you’re really not in the mood? Maybe you’re feeling under the weather; perhaps you’ve just had a fight with your significant other; it could be that there’s something else you’d rather be doing. We’ve all gone to events, put on a happy face, soldiered through, and eventually served our time and been able to depart. Sometimes we’ve been warmed up by the crowd, atmosphere and occasion and enjoyed ourselves, but often we’ve just endured.

But what happens if it’s a religious obligation, not just to show up, but to rejoice?

Sukkot in the Torah

While Torah commands rejoicing as a central aspect of the observance of all three pilgrimage festivals or shalosh regalim, the aspect of joy is given special emphasis with regards to Sukkot. In Deuteronomy we are told, “You shall rejoice in your festival, with your son and daughter, your male and female slave, the Levite, the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow in your communities. You shall hold a festival for the Eternal your God in the place that God chooses; for the Eternal your God will bless all your crops and all your undertaking and you shall have nothing but joy.”

Later sources go on to detail how joyful the celebration was. According to the Mishnah (Sukkah 5:1), “Any one who has not witnessed the rejoicings at the water-drawing, has never witnessed real rejoicing in their entire lives.” The passage then goes on to describe sages juggling flaming torches (that elective sadly was no longer offered when I was in school), everyone joining in with the playing of musical instruments, singing, and dancing. Services seem a bit tamer these days, but there is still an emphasis on joy.

What’s so special about Sukkot?

What makes Sukkot such a focal point for joy? It is the major harvest festival, Chag Ha’asif , the Festival of Ingathering, marking the completion of the fall harvest, the success of which determined whether the people would thrive or suffer during the rainy months of the winter season. It was also when prayers for rain were offered. In a climate in which there was the rainy season and the dry season, having the right amount of rain to fall at the right time was critical to survival. This, in turn raised the prominence of Sukkot to the point where it is simply referred to as HeChag, The Festival. Sukkot also comes right on the heels of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. After such an extended time of sober introspection, it is only natural to have time for release and celebration.

Nothing but joy?

While exuberant celebrating makes sense, “Nothing but joy” seems like a pretty big promise. Is that saying that if we follow all the rituals and practices to the letter, we will never know sadness and sorrow? That doesn’t make sense. All of us suffer loss. We lose loved ones to death. We lose jobs and often the relationships and camaraderie that went with them. And we sometimes see opportunities just slip away. We know that we’re not always in the mood to celebrate. And we know that bad things happen to us and around us. This past year has been an especially bad year. Everyone has experienced especially bad years: coping with the tragic loss of a loved one, with the loss of multiple loved ones, with extended periods of unemployment or underemployment, or with lingering or debilitating illness. Rarely have we had a year in which the entire Jewish people have felt loss, heartbreak, discouragement, and fear for such an extended time. With the October 7 attack, conflicts on the borders, and antisemitism exploding, joy is in short supply. So what does it mean for us to rejoice and to have nothing but joy?

Joy: Another Understanding

To make any sense of this, joy, simchah, cannot refer to everyday happiness because it is unrealistic (and annoying) to be pollyannish all the time. Therefore, it must refer to a deeper emotion or attitude. According to Rabbi Nachman of Bratzlav, the Chasidic master, sadness exists in this world. But one should pursue gloom and introduce it to joy. Or better yet, the gladness and joy will seize and transform sadness into joy. More than merely exposing oneself to happiness to feel better, Nachman is saying you really must grab hold of gloom and transform it.

This is very similar to what the late Rabbi Alan Lew wrote in This is Real and You Are Completely Unprepared:

“In the sukkah, a house that is open to the world, a house that freely acknowledges that it cannot be the basis of our security…the illusion of protection falls away, and suddenly we are flush with our life, feeling our life, following our life, doing its dance, one step after another.

And when we speak of joy here, we are not speaking of fun. Joy is a deep release of the soul, and it includes death and pain. Joy is any feeling fully felt, any experience we give our whole being to. We are conditioned to choose pleasure and to reject pain, but the truth is, any moment of our life fully inhabited, any feeling fully felt, and any immersion in the full depth of life, can be the source of deep joy.”

Rejoicing on the festival doesn’t mean just painting on a false smile; it means truly understanding and acknowledging those emotions we’ve been living with for the past year. It may be some time before we can sing with full-throated joy or dance with reckless abandon. It may even be a while before we can breathe without feeling the catch in our throats or walk without the invariable slump in our shoulders from the weight we feel we’re bearing.

It may be a while, but we will dance and sing again. Until then, we must rejoice on our festivals. We have to let go of comparisons to “normal” and like Rabbi Nachman, embrace the gloom to bring it to joy, to the sense of full release that our ancestors experienced when the Temple still stood. Because not until we have experienced the darkness, can we appreciate the joy and light.