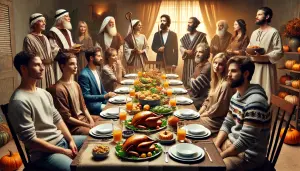

Turkey, stuffing, pumpkin pie, and families traveling across town and across country to get together. It’s our recipe for Thanksgiving. Although there’s no mention of turkey or pumpkin pie, this week’s Torah portion, Toldot (Genesis 25:18-28:9) does feature food and family and unfortunately some of the same family dynamics many of us will encounter this week. Instead of arguing about politics or football, or complaining about the dryness of the turkey, our biblical progenitors prepared meals and fought over birthright and blessings.

Rivalry: Jacob and Esau

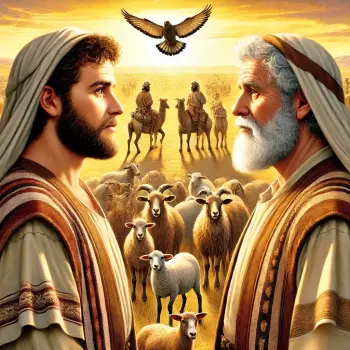

Jacob and Esau, twins as different as night and day, competed for primacy and parental love. Rebekah favored Jacob, described as a shepherd and a tent-dweller, whereas Isaac favored Esau, the hunter and outdoorsman. In the early part of the portion, Jacob demonstrates his shrewdness and cunning by agreeing to give a starving Esau a bowl of lentil stew in exchange for his birthright. The impetuous and impatient Esau agrees. The birthright assured the eldest son a double portion of inheritance. Esau, minutes older than his twin brother, would have inherited two-thirds of his father’s estate. That right of inheritance now belonged to Jacob.

While Jacob held the bulk of his father’s material possessions, Isaac’s spiritual legacy was, as yet, not transmitted. Isaac sent Esau out to prepare the wild game that he favored. Rebekah, believing Jacob to be the more deserving heir, colluded with him to prepare a well-seasoned stew from their flocks and to disguise the fair-skinned Jacob as his hirsute older brother.

The deception worked and Jacob received the blessing, as well as the birthright. A heartbroken Esau then threatened to kill him. This led Rebekah to send him to her brother Laban’s home until Esau cooled off. Many years and several Torah portions passed before the brothers eventually reconciled.

In most contemporary family get-togethers food continues to play a central role. We hope that threats of fratricide are less common, but conflict still exists. While there have been immense changes in technology since biblical times, family dynamics remain relatively unchanged. The ancient fights and struggles sound like they could be pulled from contemporary headlines.

Parental Hopes

Isaac and Rebekah each had dreams for their sons. Isaac wanted a son whose childhood and adult life would represent what he missed as he grew up. Isaac was the sheltered child, born to older parents who might have hovered over him just a little. Abraham’s other son, Ishmael, Isaac’s half-brother, had more opportunities for a rough and tumble life. Isaac was the dutiful son who did as he was told and was even prepared to be sacrificed by Abraham. Esau could do all those things Isaac had missed out on, and Isaac could live vicariously through him.

Rebekah wanted a son who would best exemplify her family’s legacy, using the mind, rather than the body. Shrewdness and cunning were more valuable than physical strength. So Rebekah taught Jacob to rely on his wits, drive a hard bargain, and find an advantage in any situation.

Are we that different today? The conflicts that we experience today are echoes of these ancient ones. We still have dreams for our children. We may or may not have every significant moment of their lives mapped out, but we often want to chart a general direction. Sometimes we want them to follow a family tradition by going into law, medicine, or even taking over the family business. Other times we want them to take on our unrealized dreams in athletics, the arts, or life journeys. Often, we lose sight of the fact that they might have their own dreams and plans. Pursuing that path does not represent parental rejection but blazing a new path and discovering an identity independent of familial desire.

Siblings Still Struggle

Siblings compete. They compete against each other for attention, affection, and recognition. At the same time they are allied against parents and classmates and often serve as the other’s first play partner. They are forever defined in apposition and opposition to each other. They complement and contradict. They can share virtually no skills or interests in common and, as time goes on, continue to take divergent paths. Just think of Princes William and Henry. Or their lives can follow similar trajectories: Venus and Serena Williams, Peyton and Eli Manning, or Chris and Liam Hemsworth. Healthy competition and support make each other better.

Finally, while there are moments of conflict, or in the case of Jacob and Esau, explosions of conflict, there is always the possibility of reconciliation. For Jacob and Esau, this came as adults, after each had enough experience of success and disappointment to be able to put youthful squabbles aside.

And that is our hope for what we might experience around the table. There will be topics over which we can never agree. There will be memories of bruised feelings and angry accusations. Ultimately the shared experiences and memories, the bonds of family, and the ways in which identity ties each of us together will lead to reconciliation. Let us be thankful that opportunity is always before us.