It’s a coincidence that that great American ritual of paying for civilization (and/or letting the military industrial complex bleed us, choose your own interpretation) falls near the Easter season. But I think even if we moved the tax filing date we’d still tend to quote the advice that poor old carpenter rabbi Yeshua ben Yoseph gave when some critics tried to trip him up with a question about taxes. According to the Gospel of Matthew (22:15-22, King James Version),

Then went the Pharisees, and took counsel how they might entangle him in his talk. And they sent out unto him their disciples with the Herodians, saying, Master, we know that thou art true, and teachest the way of God in truth, neither carest thou for any man: for thou regardest not the person of men. Tell us therefore, What thinkest thou? Is it lawful to give tribute unto Caesar, or not? But Jesus perceived their wickedness, and said, Why tempt ye me, ye hypocrites? Shew me the tribute money. And they brought unto him a penny. And he saith unto them, Whose is this image and superscription? They say unto him, Caesar’s. Then saith he unto them, Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s; and unto God the things that are God’s. When they had heard these words, they marvelled, and left him, and went their way.

(You may feel free to marvel at me quoting the gospel, and to joke about how the devil can cite Scripture to his purpose. And while Yeshua is better known by the Greek version of his name, I like to use (an English transliteration of) the original Hebrew to emphasize that I’m talking about the human mystic, not the mythological being into which he was apotheosized.)

Yeshua’s critics hit him with a tough question here. How do we keep the spirit while living in the social and political world? Let’s face it, most folks skip the dilemma by not being spiritual in any significant degree. It’s still true that the mass of people lead unexamined lives, lives of quiet desperation rather than loud inquiry. It’s sure easier that way…in the short term.

Others skip the question by leaving the social word, retreating to monasteries or convents or withdrawing into their own custom forms of isolation. That certainly has its appeal — according to the mythology it was the final temptation of the Buddha, to just sit under the Bo Tree in enlightened bliss and not bother with the mass of suffering sentient beings. This sort of “leaving the world” is considered noble by many, but we have to understand it as a dodge, a cheap way out. It’s relatively easy for a monk to sit in mediation or prayer in some temple on an isolated mountain where every aspect of daily life is designed to re-enforce his practice; but if that practice is too fragile to stand exposure to the mundane world, what’s the use?

And speaking of temptations, I suppose we ought to consider a third solution offered in one of the legendary temptations of poor old Yeshua: to take power in the social world, to become a king and thus able to bend the social order to one’s spiritual desires. It’s not a practical option for most of us to even attempt, and history suggests that it generally doesn’t end well for those who do. You can’t make the grass grow by pulling on it, and you can’t forcibly drag the social order into spiritual enlightenment.

But if we decide to stay in the world, if we don’t take any of these dodges, then what? If rather than retreating to the mountain temples or going off into isolation in the desert we choose the path of sitting zazen or meeting in circle and then leaving the cushion or the altar to deal with the mundane, to handle the workday or taking care of the kids or fighting for social justice, what then?

How shall we deal with the everyday challenges of right speech, right action, and right livelihood in an honorable fashion?

According to Yeshua, part of the answer lies in making a division between that which is Caesar’s and that which belongs to the God’s.

In less theistic terms, some things belong to the social order, and we deal with them as citizens, through social and political processes. As Yeshua noted, money is a creation of the state, a thing of Caesar. This is true for property in general; it’s why “property rights” are not central to the teachings of the Buddha or the Christ or any spiritual teacher.

That doesn’t mean that we can avoid the necessity of being good citizens, of working politically for a state that meets the needs of all human beings. Spiritual teachings speak to why we should give a damn about other human beings in the first place, and if we have that in place the political end of things should eventually work itself out. If not, then Thoreau’s words from Civil Disobedience apply: “A very few, as heroes, patriots, martyrs, reformers in the great sense, and men, serve the State with their consciences also, and so necessarily resist it for the most part; and they are commonly treated by it as enemies.”

But that sort of resistance is still part of the political process, the realm of Caesar.

Yeshua tells us that there are things outside that realm. He tells us to render onto Caesar those things that are Caesar’s but he also says there are things that are not Caesar’s.

There are things that must always be taken as beyond the authority of kings and legislatures and the voting public. Even in the best possible utopian state, there are things that we deal with not as citizens but as seekers, shamans, kosmos and prophets en masse, priests unto ourselves.

Some things are, in word, sacred.

And if those sacred things are violated, Yeshua also had a plan for how to deal with that. As he demonstrated when some unsavory types set up shop in the temple, it involved channeling some wrathful deity energy and the application of a whip to the defilers. (John 2:14-16)

Now, perhaps the most important of these sacred things is the human body. Christianity often tends to denigrate the flesh, but even poor screwed-up Saul of Tarsus (a.k.a. Paul the Apostle), as infected with misogyny and fear of sex as he was, couldn’t deny the divinity of the human body. He famously wrote “What? know ye not that your body is the temple of the Holy Ghost which is in you, which ye have of God…?” (1 Corinthians 6:19) (Though that passage is buried in a screed about the dangers of “fornication”.)

There’s a reason that Yeshua went around healing people’s bodies, after all: he was tending to sacred things. The Buddha also tended to the sick, though (as far as I know) without miracle stories about it. And the great Zen teacher Ikkyu saw nothing profane about the body: “my dying teacher could not wipe himself unlike you disciples / who use bamboo I cleaned his lovely ass with my bare hands”.

I’m reminded of the words of Uncle Walt, America’s poet and prophet: “I keep as delicate around the bowels as around the head and heart”. Why was that? Because, he said, “I sing the body electric…If any thing is sacred the human body is sacred… / O my body! I dare not desert the likes of you in other men and women, nor the likes of the parts of you, / I believe the likes of you are to stand or fall with the likes of the soul, (and that they are the soul,)…”

It’s unfortunate that a trend of hatred and denigration of the body — indeed of the physical world in general — has persisted in the Western philosophical tradition at least since Plato. And some teachers in the East have fallen into the same trap; the Buddha nearly died from extreme flesh-denying asceticism before he learned better. In contrast Taoist masters were wise enough to seek physical immortality — not some airy-fairy disembodied spiritual thing but the preservation of a healthy fleshly body. This concern for the body is at the root of classical Chinese Medicine.

If there is anything in this world that is holy, it is the human being. More holy than any book, than any idea, than any building or creed or relic. And the human being is not a pure and immaterial and immortal soul somehow temporarily linked to a corrupt and rotting chunk of meat. A human being is an act performed by a body, the result of a body, generated by a body. That which we call “soul” or “spirit” is nothing but that dance considered in the most abstract and mystical sense. As an inherent and necessary part of the sacred human being, the human body is holy.

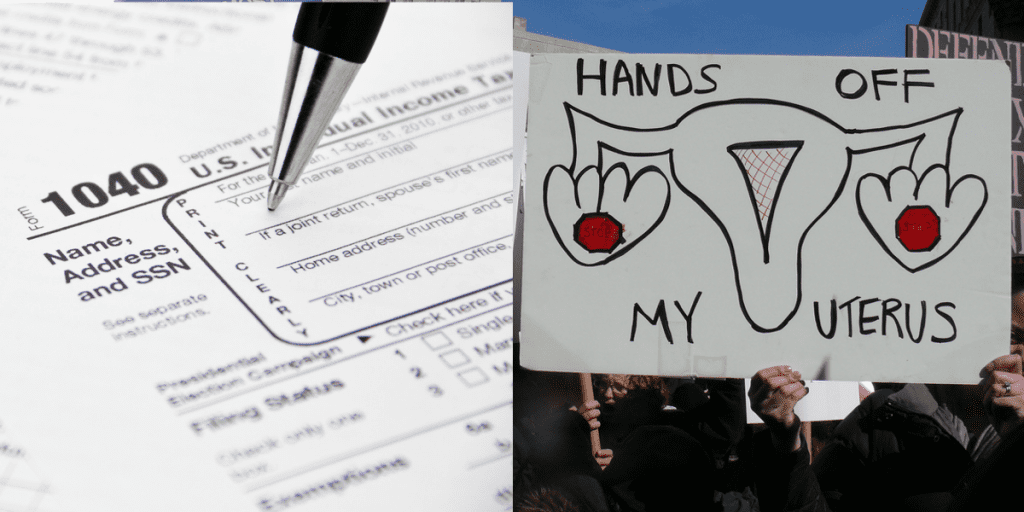

And yet how is this sacred and holy body treated by the state? The bodies of men (and now sometimes of women too, but still mostly of men) are the gambling chips of war, wagered by the state in hopes of gaining some territory or power. The bodies of women are to be controlled, their role as wombs for the next generation of soldiers and laborers and taxpayers to service the state is to be paramount.

The state claims the power to seize the very living flesh of citizens. We are to render unto Caesar blood and skin, for drug testing and DNA analysis.

No, I say. The sovereignty of the state ends at my skin.

If I play the game of property, where the state takes the naturally free and open world and privatizes it, I can’t complain overmuch at the idea of that same state taking as a ante for that game some of the property that I controlled for a while. Any claim of property ultimately rests of some act or authority of the state (a land or resource deed, a copyright or patent or corporate charter), so Caesar has earned his cut. Fine.

And If I want to call upon the state to protect me and my community from those who would do violence, I can’t complain overmuch at the idea of it possibly detaining those who behave badly. If you’re going to have police, you’re going to have arrests. Okay.

I’m not thrilled at the idea of taxation and imprisonment, and we must act as citizens to see that they are applied wisely; but until we reach Universal Enlightenment and the state can be abolished, until men are prepared for that best government, which governs not at all, the state will exist; and taxation and coercion are its nature. So long as taxation is fair and with representation, and coercion is done with due process of law and respect for human rights, I shall not object overmuch.

But when the state seeks to extend its power into my body or the bodies of my fellow citizens, that is another matter.

That is not merely bad politics. It is sacrilege, the violation of the sacred.

And from trans-vaginal ultrasounds to DNA collection to random roadsize testing of driver’s breath, blood, and saliva, it seems to be increasing.

It needs to be pointed out that nothing that happens inside the skin of one citizen can directly affect another. So there is no compelling state interest in any of these measures. Women and their doctors are quite capable of deciding on appropriate medical procedures. If the state has a DNA sample of a rapist or other attacker and wants to check it against a suspect, a search (with probable cause and a warrant!) of that suspect’s home will turn up a number of skin flakes and bits of hair that can be tested. And impairment testing and laws against reckless driving in itself are far more relevant to intoxicated driving than any chemical screen.

The only reason for the state to claim such authority of the bodies of its citizens is because it thinks these bodies are its property. It is the ne plus ultra of authoritarianism; once people are accustomed to the state having dominion over their bodies, they will accept any claim of authority.

When the body is not sacred then nothing is sacred, there is nothing outside Caesar’s realm. “Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s; and unto God the things that are God’s,” but when Caesar is made a god, unlimited in power, what then?

You can keep up with “The Zen Pagan” by subscribing via RSS or e-mail.

Detail TBD, but I’ll be at the Free Spirit Gathering this June, and the Starwood Festival this July.

If you do Facebook, you might choose to join a group on “Zen Paganism” I’ve set up there. And don’t forget to “like” Patheos Pagan and/or The Zen Pagan over there, too.