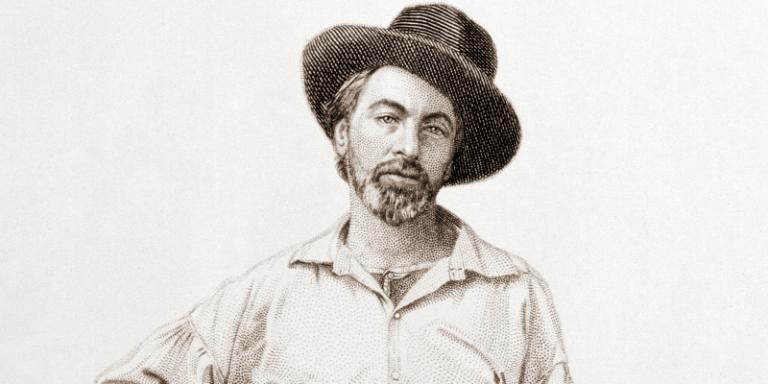

If you’ve read Why Buddha Touched the Earth, you may recall me talking about the 19th century Transcendentalist writers as important forerunners of the Neopagan revival — especially Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Walt Whitman.

(Academics sometimes argue whether Whitman was really a Transcendentalist or not. Academics are silly sometimes; if you prefer to use some other word to denote the social and literary milieu that included these three key American intellectuals, feel free to substitute it.)

May 31, 2019 marks the 200th anniversary of Whitman’s birth. It seems appropriate to reflect on his legacy.

There is a direct chain of inspiration from Whitman to the important occultist and Pagan figures Aleister Crowley, Dion Fortune, and Gerald Gardner, via the English poet Algernon Charles Swinburne.

Swinburne was a Whitman fan during the time he produced his most significant work — even writing a poem “To Walt Whitman In America”: “O strong-winged soul with prophetic / Lips hot with the bloodheats of song”. (Though they had something of a falling out later.) According to historian Ronald Hutton, Crowley, Fortune, and Gardner were all influenced by Swinburne. (Crowley even canonized Swinburne as a saint of the Gnostic Catholic Church.)

So what was the big deal with Whitman? Whitman said of his Leaves Of Grass that it is “avowedly the song of Sex and Amativeness, and even Animality – though meanings that do not usually go along with those words are behind all,” and cited “the ancient Hindoo poems” as being among his inspirations.

In this he is emblematic of a trend among some 19th century Western artists and intellectuals, shaken by the rapid changes industrialization and the rise of the natural sciences were working on society, to look at the natural world and at other cultures (both looking to the European past, and to other parts of the world) to find a spiritual solution that their mainstream Christianity seemed unable to provide.

Following is an excerpt from Why Buddha Touched the Earth about these writers.

I’m coming to see that the writers of the Transcendentalist movement – primarily Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman – had a vision of the Unites States as a world leader. But their vision was not of political leadership, or of military power, or even of mere artistic and cultural prominence; they saw their nation as a spiritual model for the world.

It was 1837 when Emerson gave his landmark lecture “The American Scholar”: six decades since the American colonies had declared their political independence, and a quarter-century since they had made it stick in the War of 1812. But like a teenager who has just moved out on his or her own, the U.S. still sought to define its own identity.

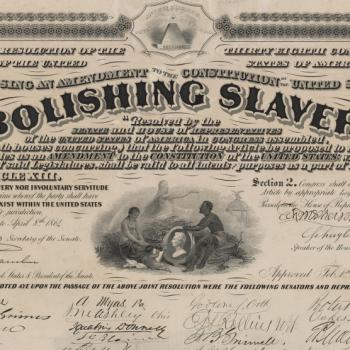

In literature and the arts it still looked to England rather than to any domestic tradition. Socially and economically it was dealing with the Industrial Revolution, and in politics it still wrestled with issues its Enlightenment-inspired founders hadn’t settled – chiefly, slavery.

The question, “just what is America, anyway?” was being urgently explored, and was so divisive that within Emerson’s lifetime tens of thousands would be killed trying to settle it by force.

Tumultuous times have often given impetus to spiritual or religious movements. The turmoil caused by plagues and “barbarian” attacks helped open the way for Christianity in Rome. The “Little Ice Age” and the Black Death caused such disruption in Europe that the Catholic Church split in two, each side claiming to have the genuine Pope. It was only was 25 years between Columbus’s voyage and Luther’s theses, and six years between the start of the English civil war and the beginning of George Fox’s preaching career, the start of the Quakers.

Just so, the turmoil and conflicts of early nineteenth century America gave birth to a mass revival of “primitive” Christianity, the “Second Great Awakening”. But in New England a more ecumenical and intellectual trend gave birth to the Transcendentalist literary and religious movement. They had a vision that was in some ways similar to that of the Puritan colonists, who saw the new nation as a shining “city upon a hill” that would be a guide to the world. But where the Puritans sought to build a rigid order based on received Biblical truth and a structured clergy, the Transcendentalists wanted to enable each person’s individual and direct religious experience.

As Whitman wrote in the preface to the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass:

There will soon be no more priests. Their work is done. They may wait awhile … perhaps a generation or two … dropping off by degrees. A superior breed shall take their place … the gangs of kosmos and prophets en masse shall take their place. A new order shall arise and they shall be the priests of man, and every man shall be his own priest. The churches built under their umbrage shall be the churches of men and women. Through the divinity of themselves shall the kosmos and the new breed of poets be interpreters of men and women and of all events and things. They shall find their inspiration in real objects to-day, symptoms of the past and future…. They shall not deign to defend immortality or God or the perfection of things or liberty or the exquisite beauty and reality of the soul. They shall arise in America and be responded to from the remainder of the earth.

Their vision was not only more individual and mystic than that of mainstream Christianity, it was also very heterodox: they were among the earliest Westerners to take a serious interest in Buddhist and Hindu thought. According to historian Arthur Versluis, the Transcendentalist movement was partly a product of such currents of Western thought as Unitarianism and Puritanism, but also of “contact with the world religions, especially Hinduism and Buddhism, which was largely seen in the light of ‘universal progress’.”

…

Both directly, and through their inspiration on the Beat poets and writers of the mid-twentieth century, the Transcendentalists had a tremendous influence on the development of Buddhism in the West.

They also helped promote to industrialized Western civilization the idea that contemplation of nature could be a spiritual activity, and their works are widely cited as examples of pantheism. Thoreau’s Walden remains a masterpiece of nature writing, while Emerson wrote of the ordinary miracles of nature:

‘Miracles have ceased.’ Have they indeed? When? They had not ceased this afternoon when I walked into the wood and got into bright, miraculous sunshine, in shelter from the roaring wind. Who sees a pine-cone, or the turpentine exuding from the tree, or a leaf, the unit of vegetation, fall from its bough, as if it said, ‘the year is finished,’ or hears in the quiet, piny glen the chickadee chirping his cheerful note, or walks along the lofty promontory-like ridges which, like natural causeways, traverse the morass, or gazes upward at the rushing clouds, or downward at a moss or a stone and says to himself, ‘Miracles have ceased’?

And Whitman wrote of a love for the Earth with erotic overtones:

Press close bare-bosom’d night – press close magnetic nourishing night!

Night of south winds – night of the large few stars!

Still nodding night – mad naked summer night.

Smile O voluptuous cool-breath’d earth!

Earth of the slumbering and liquid trees!

Earth of the departed sunset – earth of the mountains misty-topt!

Earth of the vitreous pour of the full moon just tinged with blue!

Earth of shine and dark mottling the tide of the river!

Earth of the limpid gray of clouds brighter and clearer for my sake!

Far-swooping elbow’d earth – rich apple-blossom’d earth!

Smile, for your lover comes.

Prodigal, you have given me love – therefore I to you give love!

O unspeakable passionate love.

In their syncretism – Whitman, for example, said that he “had perfect faith in all sects, and was not inclined to reject a single one” – in their insistence on individual experience over revealed truth, and in their love of nature as a spiritual force, we can see much that contributed to the modern Pagan movement.

It might even be argued that, depending on definitions, the Transcendentalists were the first American Pagans. Tim Zell, who was one of the first to use the word Pagan in its modern sense, included them in an explanation of the term in the newsletter Green Egg in 1968.

…

But whether we draw the lines of these movements to include them or not, the Transcendentalists certainly laid down a groove that influenced the later development of Paganism and Buddhism on American shores. They prepared the ground that would receive the seeds of modern witchcraft and occultism from Britain, and the seeds of Buddhism – especially of Zen – from Asia, and sprout forth many strange and interesting flowers in the twentieth century.

They were just one thread in the tapestry of the Buddhist and Pagan revivals of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: a strange weave of poets, Theosophists, Buddhists, magicians, witches – and jesters.