In my previous post (http://www.patheos.com/blogs/tomhobson/2018/05/back-to-the-second-century-echoes-of-modern-heresy/), we began to explore how today’s church is re-living the world of heresy of the second and third centuries AD. Today we continue with a brief look at how this was true for the Gnostics, and how we now find ourselves where no one is in a position to exercise effective church discipline over the mess of heresy that surrounds us.

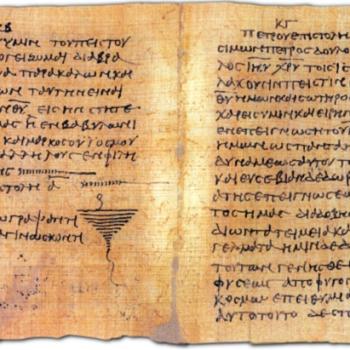

The field of Gnosticism is too wide to examine it in detail in its entirety. What all brands of Gnosticism have in common is their redefinition of words. Until the latter part of the second century, the Gnostics did not have their own scriptures, so they had to borrow our canonical writings and use our words to communicate very different doctrines. No one has been more creative than the Gnostics in redefining words such as “God” and “Christ” ad nauseam, which should serve as a warning to us, who live in a church that seeks to find unity around words with fill-in-the-blank meanings.

The Gnostics were famous for having secret words of Jesus and secret meanings of Scripture. I was reminded of the Gnostics about 20 years ago when David Buttrick did a preaching seminar in Des Moines Presbytery. Buttrick advocated an approach to the Bible where virtually none of it means what it says; it is full of coded messages that no one would pick up if they took the text literally. Which led me to wonder, How and why are we supposed to read the Bible if none of it plainly means what it says, if you have to be “in-the-know” (the meaning of the term “Gnostic”) to understand what it says?

While Gnosticism resembles modern progressivism in its redefinition of words, where it differs from today’s progressivism is that it was definitely not pluralistic. Both sides, Gnostic and orthodox, denied the salvation of their opponents, and denied the truth of their opponents’ message.

At this time, there was no centralized authority in the church to exercise discipline. But neither was there any true connectionalism like the kind we have today. It was a Wild West, with local bishop versus local bishop. Heretics could be ejected from one local body, but there was no way to enforce excommunication across geographical boundaries. Even two bishops of Rome (proto-“Popes”, as it were), Zephyrinus and Callistus, got it wrong on the issue of the Trinity versus modalism (the teaching that God has existed in only one “mode” at a time: first as Father, then as Son, now as Holy Spirit). Only when Christianity became the official religion of the Empire did connectionalism arise through which church discipline as we know it could be exercised on a church-wide scale.

What Scriptures can we apply to the new reality in which we minister? Paul writes in 1 Corinthians 5:11 that we must not associate with anyone who claims to be a brother or sister who lives a self-affirming sexually immoral lifestyle (along with other serious moral issues he names); “with such a person do not even eat.” What does that do to lunch at presbytery? One recalls the 1999 meeting between Jerry Falwell and gay activist Mel White and their respective supporters, where ice water was served, but no food was shared. (https://www.salon.com/1999/10/25/falwell/)

John writes that if anyone comes to us who holds a false doctrine of Christ, “Do not receive them into your house or give them any welcome. Whoever welcomes them, shares in their wicked work.” (2 John 9-11) When Mormons or Jehovah’s Witnesses, who hold to very different understandings of who Jesus is than we do, ring our doorbell, John gives us reason not to let them inside our door, unless by doing so we are able to build a relationship for sharing the Gospel, a relationship that does not communicate agreement. The question is whether this principle may also be applied to our relationships to ministerial colleagues who are in clear, open apostasy. Do we communicate support by our association with them?

We can only say that 1 Corinthians 5:11 and 2 John 10-11 do not apply to our present situation, if we set aside any pretense that our mainline denominations are “churches” in the Scots’ Confession definition of the word. We must accept the truth that in many of these churches, discipline is a joke, broken beyond repair, and the Word is not rightly preached today in those churches any more than it was in the age of Gnosticism.

Only if we shift our concept of the visible church to that of a voluntary organization, or of a mission field where believer, heretic, and pagan all compete on the same field to win souls, can believers within the mainline churches continue to operate business-as-usual. Such an approach would no longer be business as usual, because it would require a huge ideological shift between our ears. But it is a shift that many have already made, consciously or unconsciously, for sanity’s sake and for integrity’s sake, in order to continue to serve in their church.

The period of the Gnostic threat, I propose, could provide the most helpful road map for negotiating the terrain of the church today: a disconnected church, where orthodox and Gnostic congregations and bishops operate side by side, moving back and forth, with non-geographic boundaries, with no Rome or Louisville to referee, where joint projects of love and justice could be conducted on the same basis as we conduct such projects with Jews, Muslims, and other non-Christians. To operate otherwise, I propose, is to impose a yoke that doesn’t fit the reality.

Irenaeus (whose name means “Peaceable”), the Walter Martin anti-cult guru of his day, concludes Book III of his work Against Heresies with these irenic words: “This is our prayer for them [i.e., that they may not continue in the ditch they have dug for themselves]; we love them more expediently than they love themselves. For since our love is true it saves them, if they accept it. It is like a harsh medicine that eats away the foreign and superfluous flesh formed on a wound; it takes away their pride and exaltation. This is why we shall try, with all our strength and without weariness, to offer them our hand.”