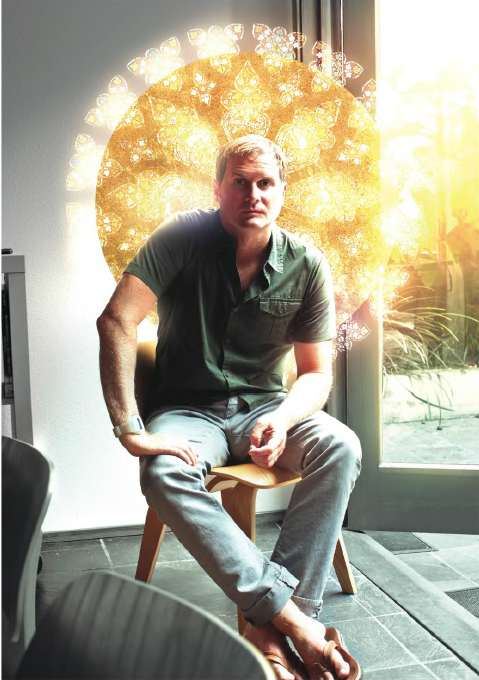

A couple weeks ago, I watched (and blogged about) the David Di Sabatino documentary film, Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher. David was kind enough to drop me an email after that post, and kinder still to send me a copy of his more recent film, Fallen Angel: The Outlaw Larry Norman.

It’s odd that I ever got into Larry Norman music when I was in high school, but I did. In spite of growing up in a mainline Congregational church and having to this day never heard a Randy Stonehill song (as far as I know), someone turned me on to Norman’s music and I loved it.

I didn’t get the millenial theology, that’s for sure — famously, Norman’s song, “I Wish We’d All Been Ready” was used in the campy Christian rapture film, A Thief in the Night. And Norman’s music didn’t sound like the other Christian rock that my evangelical friends foisted upon me: Petra, White Heart, and Stryper.

Instead, Norman’s music sounded more like my favorite music: Led Zeppelin and their ilk. His songs were often driven with acoustic blues rhythms, and his lyrics were shockingly raw:

Gonorrhea on Valentine’s Day,

and you’re still lookin’ for the perfect lay.

Why don’t you look into Jesus,

He’s got the answer.

That was all a bit of a neck-snapper for this nice, white suburban boy.

The fact is, it was clear to me even in the 1980s, when I was listening to Norman’s music on cassettes in my 1976 Ford Pinto hatchback that he was from a different version of Christianity than I. I wondered what, if anything, I had in common with the Christianity that he was singing about.

I wonder that less today, but I am even more fascinated by Norman, Frisbee, and the Jesus Movement revival in the 1970s. Fallen Angel isn’t particularly kind to Norman, but only because it tells the truth. Like so many other gifted artists, he was tragically flawed and left a wake of broken relationships (including an unacknowledged son in Australia) and sour business deals behind him. Throughout the many interviews in the film, the main feeling among those interviewed seems to be that they’re shaking their heads and wondering what-could-have-been. And, not coincidentally, that’s almost verbatim what Chuck Smith, Sr. says at Lonnie Frisbee’s funeral in that film.

Both Frisbee and Norman died pretty much alone, far from the adoring throngs of fans that they’d known in the 1970s. Maybe they were abandoned by the church (as they both claimed), or maybe they pushed the church away by their strange and sometimes abusive behavior. Or, most likely, it was a combination of the two. But, in any case, I’ve found both of Di Sabatino’s films to be poignant and tragic, and to open a window into an aspect of recent Christian history with which I was previously unfamiliar.