Last week, Stephen asked a great question. Here’s the punchline:

Progressives then have a problem with the God of most traditional and especially Christian formulations – especially with retribution, punishments, curses, condemnations, as well as problems with the unfairness of the treatment of women, slaves, and other outsiders. This gives us a huge problem with the bible and the god it describes, which forces us to re-think everything. Thus our problem speaking much, or coherently about God. Where do we go for information?

So, where do Christian progressives go for moral authority?

First, a note on Questions That Haunt. Obviously, I’ve struggled to keep up with the Tuesday-Friday rhythm. I’m going to keep trying to live up to this, but I may have to adjust the schedule it I can’t. QTH has become among the most popular features on Theoblogy, and I am grateful to all of you who have made it so.

On a related note, I’m going to take a different tack this week. I’m going to excerpt and comment on a couple of my favorite comments from last week’s post. They’re so good that they really get at what what I was going to say. Here goes:

Scott Paeth asked,

Related question: What is a moral foundation anyway? And why would one need one?

Scott went on to post a lengthy answer on his own blog (to which you should subscribe):

Why would I think that moral foundations may not be necessary? A lot depends on what you think it means to have a moral foundation. The question implies that a moral foundation must be some sort of absolute, unchanging, and completely infallible guide to behavior. Morality, in such a description of a moral foundation, is simply a matter of checking your behavior against the list of rules provided by whatever your foundation may be.

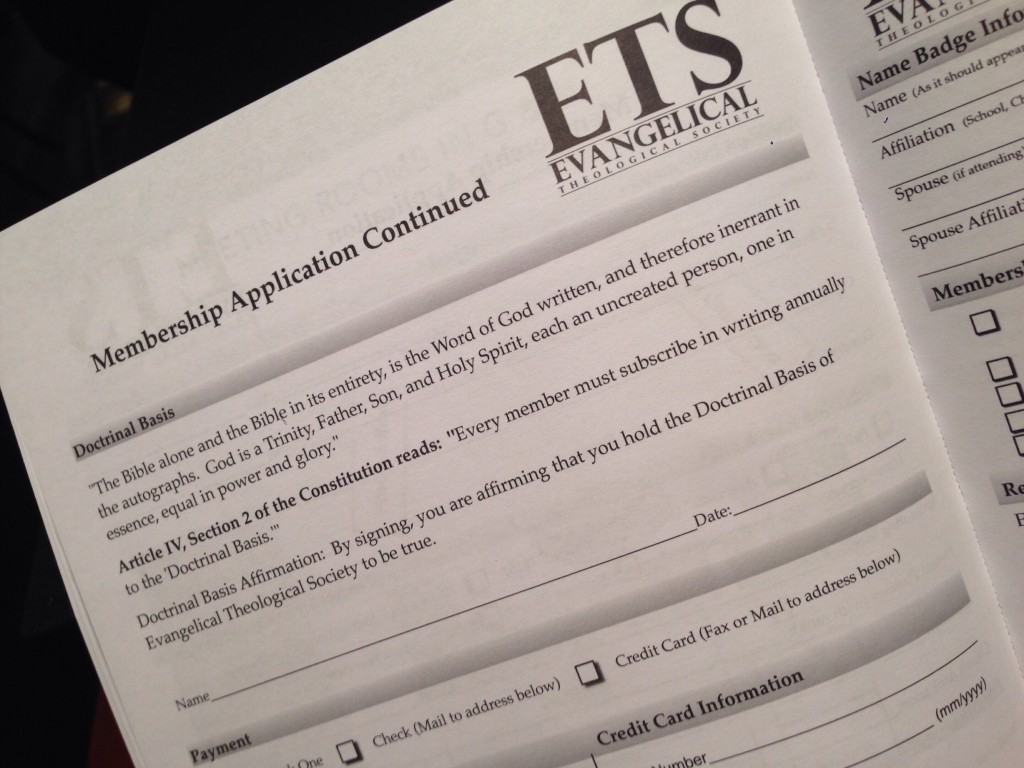

I agree with Scott (and Jack Caputo). We don’t need a foundation. In fact, I argued in my very first book that foundations are a modern invention — it’s a unicorn. Someone made up “foundations” even though they don’t exist. Human reasoning doesn’t work in a bottom-up kind of way, like there’s an indubitable foundation upon which we build all of our knowledge. Instead, human reasoning works like a web (I wrote, following W.V.O. Quine).

Craig points us to a related concept, “reflective equilibrium,” which was introduced by John Rawls but I came to by way of Jürgen Habermas:

The method of reflective equilibrium consists in working back and forth among our considered judgments (some say our “intuitions”) about particular instances or cases, the principles or rules that we believe govern them, and the theoretical considerations that we believe bear on accepting these considered judgments, principles, or rules, revising any of these elements wherever necessary in order to achieve an acceptable coherence among them. The method succeeds and we achieve reflective equilibrium when we arrive at an acceptable coherence among these beliefs.

Indeed, this is how moral reasoning actually works. We achieve a wide, reflective equilibrium. This equilibrium is both fragile and temporary.

Take, for example, the issue of same sex marriage. Approaching the election last November, my help in the fight against the amendment was basically ignored by Minnesotans United for All Families. After several meetings with people on their faith outreach team, my contributions were not needed. It was decided that the one and only way to get people off the fence on the issue of marriage equality was for them to hear the stories of gay people. And it obviously worked. The amendment was defeated by a wide margin.

It’s true: people change their mind on the issue of homosexuality when one of their children comes out. Or their nephew or niece. Or their spouse. Relational moments like this tend to rupture a person’s reflective equilibrium.

But, I argued (to deaf ears), when people hear the stories of gay persons, they need a new theology to replace the old one. When the equilibrium gets disequlibriated, a person will attempt to find a new equilibrium. Sadly, that often means that people leave Christianity altogether.

Another example: In Kuala Lumpur, I met guy who was a former evangelical missionary to Japan. He has since lost his faith. He told me that Hell was the linchpin to his Christian faith, as taught by his family and his church. But once he become convinced that Hell wasn’t real — once he removed that linchpin — there was no need for Christianity at all.

I suppose that someone could see this as a foundation crumbling, but that’s not what happened. It’s not that this guy has no more moral system. It’s that his fragile equilibrium was shattered, and he has since found a new equilibrium that no longer includes Christianity. He underwent a theological rupture, not a relational one.

Similarly, we can all think of persons who’ve got gay children, but they have not relinquished their anti-gay theology. Their equilibrium holds, in spite of relational pressure on it. These people, I argue, need a theological rupture to disrupt their equilibrium, even more than a relational rupture. (I had this very argument with a staff member of MN United, to no avail.)

Foundations lead to fundamentals, and fundamentals cannot hold. Moral reasoning doesn’t actually work that way. By building your rationality (or faith) on a foundation, you’re building it on something that doesn’t actually exist. By recognizing that we come to our moral convictions through a process that is, just that, a process, we will not only have more understanding of others, we’ll also have more grace with ourselves.