Last Tuesday’s Question That Haunts Christianity came from Chris:

This question has been bugging me for a while. To preface, I consider myself a progressive (certainly ex-evangelical) Christian. My question relates to ethics in general and the Bible in particular. We all assume that there is a particular way that each of us SHOULD or SHOULD NOT act. I.e., we all harbor the notion that some acts are inherently moral or immoral. As a progressive, I don’t consider the Bible itself to be the “Word of God” or some kind of objective moral authority. I consider (as I’m sure many of your readers do) it to be a collection of writings that detail the experiences of the authors with the divine. As such, it is just as captive to subjectivity as the rest of us are.

If this is the case, however, how is it that we are to determine moral decisions? If there is no objective moral authority we can point to in order to determine an ethical system, what are we left with? (These are honest questions I have been wrestling with, as I continue to struggle between determining the possibility of access to SOME kind of objectivity, if that even exists).

Great and numerous comments ensued here. My $.02:

Chris is touching on a problem that is vexing to very many people. It is, for instance, at the heart of many people’s fear that if they give up on an historical Adam and Eve, the entire biblical house of cards will collapse. And that fear, in turn, leads to laughable creation museums that, by extension, make all Christians look foolish.

Many people fear the slippery slope. The worry is that, once you’re on the slippery slope, you’re destined to slide to the bottom, and pretty soon you’ll be having sex with goats and murdering your neighbor. But that’s simply not true. We all live on the slippery slope. The question is how one lives on the slippery slope. Or, in other words, how one manages one’s life in the midst of myriad relative choices every day, not least of which is how to interpret various Bible injunctions.

Commenter CurtisMSP made this point:

Morality changes over time and place. What was moral in 1400 in Mexico was not moral in 1200 in Germany, was not moral in 2000 in Bismarck. Morality is based on people and culture. Moral authority exists in the people and culture that surround each time and place. If you want to determine what is moral in a given situation, you must listen to all of the surrounding people and culture. The consistency lies in the listening.

Aristotle made this same point millennia ago. In the Nichomachean Ethics, he argued that a polis is a self-inscribed moral territory. So, say you live in a polis in which murder is unlawful and immoral. Aristotle says that you cannot go visit another polis, see them murdering each other, and proclaim, “Don’t do that! Murder is universally immoral!” Instead, each polis works by a particular moral language and framework that has developed over time; in their context, it works perfectly. It doesn’t work if you don’t share that language and that history and those particular practices.

This Aristotelian thinking was recovered in the Scholastic period by Thomas Aquinas, and re-recovered in the 20th century by thinkers as diverse as George Lindbeck, Hans Frei, Alaistair MacIntyre, Stanley Hauerwas, and Will Willimon — the book co-written by the lattermost two, Resident Aliens, is the classic, popular articulation of this thinking in ecclesiology. Therein they argue that the church lives by its own set of languages and practices, and these often run counter to the language and practices of consumerism, militarism, and even liberal democracy.

While I have some quibbles with Neo-Aristotelianism (which I will unpack in my talk at the Progressive Youth Ministry Conference), in general I think that this is the most potent response to the relativism that is baked into the cake of postmodernism.

The question isn’t really whether objective reality exists or not. Even if it does — and it very well may — it is inaccessible to us. It makes no sense for us to talk about it, since we are finite and subjective beings at our very core.

But what we’ve got is each other. This is the most valuable recovery of the ancients during the postmodern era: that all truth is ultimately relational truth. The American pragmatist school says it this way: truth works.

Communities of people agree on what is moral, and the Bible that Chris and I revere so highly is a record of an archetypal community’s working out of truth, of figuring out what works. Murder doesn’t work. Neither, it seems, does eating pork.

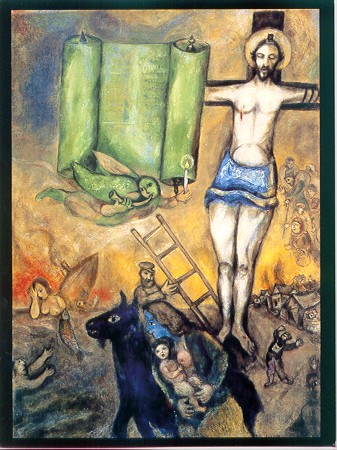

Anything that I’ve said so far would work, with or without a divine being. I happen to believe that God is relationally involved with us — that God was involved in the community of Israel, and that God was ultimately, uniquely, and eternally connected to the human community in the person of Jesus.

But now the interpretative works continues. It seems, based on the experiences of the first Christians in the book of Acts and the communities of faith begun by Paul, that we work out the truth of Christianity best in small, ecclesial communities. The Bible does not prescribe how a community of faith deals ethically with a loving, adult, monogamous lesbian couple, nor does it tell us whether clones can serve as elders in a congregation. We’ve got to work these things out in community.

That’s why I like when we at Solomon’s Porch refer to the Bible as a member of our community. We argue with it, debate it, challenge it. It is an authoritative member of our community — that is, it has a certain authority — but it is not a dictator.