Visionings is a series that explores sight and seeing.

Recap

This is the third piece focused on icons. In the first, I offered a general introduction to icons. The last one was a guide to praying through them. In this piece, I am highlighting the work of a remarkable contemporary iconographer named Khrystyna Kvyk with an interview.

Introduction

Khrystyna Kvyk (1994 – ) is a Ukrainian iconographer. She is part of the Ukrainian

Greek-Catholic Church, a church that maintains the Byzantine liturgical tradition as well as Eastern iconography.

From a very young age Kvyk desired to be an artist. Though she now understands her calling from God to be an iconographer. This wasn’t always the case. In fact, she resisted the possibility for many years. Nevertheless, her passion for iconography was first kindled around the age of 16 when she attended classes on iconography at the invitation of a priest with a fine arts background. At a local monastery in a small village in the mountains, this priest and his artist friends offered iconography courses with the hope of reviving the ancient Western-Ukrainian icon. At this monastery, she was exposed to the spiritual and technical methods of iconography; the seeds were planted.

From a very young age Kvyk desired to be an artist. Though she now understands her calling from God to be an iconographer. This wasn’t always the case. In fact, she resisted the possibility for many years. Nevertheless, her passion for iconography was first kindled around the age of 16 when she attended classes on iconography at the invitation of a priest with a fine arts background. At a local monastery in a small village in the mountains, this priest and his artist friends offered iconography courses with the hope of reviving the ancient Western-Ukrainian icon. At this monastery, she was exposed to the spiritual and technical methods of iconography; the seeds were planted.

After graduating from college some years later with a focus on graphic design, she followed that same priest’s footsteps and enrolled in his alma mater. In the Department of Sacral Art, Kvyk earned a Masters degree in 2020 at the the Lviv National Academy of Arts (LNAA). It is the community of professors and classmates at this school that has most shaped her style as an artist and iconographer.

Kvyk is a core part of the new movement called the Lviv School that is pushing the boundaries of iconography. The interview helps us see this the iconography through the eyes of a contemporary artist.

This interview was done via email and has been edited for length and clarity.

Creating an icon requires the painter to be technically skilled, but it is also a very spiritual endeavor. I have even heard some artists describe their painting as a kind of prayer. Is this your experience? How has this creative worked shaped you spiritually?

The original task of the icon was to inform uneducated people about the doctrine of the Christian faith. Now, it serves as a supplement to the doctrine because most people are now educated. But the main purpose of iconography is the same: conveying the faith to as many people as possible.

At first I thought that I must be perfectly attuned to the Holy Scripture and know all the truths of Christianity to be qualified to paint icons. But I actually got my start in iconography like an uneducated person. After I began, the desire anc capacity to conceptualize God and the central ideas of Christianity grew.

In terms of the relationship between painting icons and my spirituality, creating them begins with reflecting on biblical stories. It’s a a kind of dialogue between the artist and Christian ideas, between humans and God. Of course,iconography is a form of prayer and in my case it’s more than just prayer because it leads me to the truth about Christ step-by-step and enriches me spirituality.

Icons help to improve my understanding of the Christian faith. It requires learning and reflecting all the time and it shapes my faith. Through painting icons, my understanding of the metaphorical meanings and complex symbolism of Christianity has grown so much. My passion to create art and my faith coexist in symbiosis.

Can you describe the process of painting or writing an icon?

In Ukrainian we say “to write” when it comes to any kind or genre of painting (landscape, portrait, oil painting, watercolor etc). But writing or painting are interchangeable as far as I’m concerned.

The process of painting an icon is quite laborious. The main professional task of a modern iconographer in creating new icons is to choose a prototype for future work. The choice of artistic landmark may be limited to issues of stylization (e. g. partial imitation, imitation in some details).

I search for visual language in ancient Byzantine sacred art, delve into various creative practices both contemporary and ancient, and sometimes even look for inspiration in naive and folk art. I try discard less important elements to focus on the essence.

At first I do some research about a topic I have selected if I need it and make a few sketches but sometimes when I have a vision of the whole picture I limit myself with just linear sketch to dedicate more time for painting the icon itself.

Then I prepare the board impregnating it with glue, glueing the canvas, putting gesso, grinding or polishing. I’m unsure if it’s necessary to go into details about the technology.

The traditional technique of iconography is egg tempera but due to many conditions and my busy schedule I have now given up on tempera in favor of acrylic as it’s much more permanent, less vulnerable to mechanical damage, andallows you to get the work done much faster.

The painting itself I start with making a drawing and covering large planes. After that I continue painting details carefully. It’s important for iconography every layer of paint be transparent to express the idea of light. But in fact there can be diferent approaches of putting the paint accepted according to technique and artist’s manner. Egg tempera requires putting transparent layers and acrylic allows using multiple different ways of painting. I prioritize image I get as a result and symbolical meanings of depicted subjects over strictly following the ancient technique.

I tend to make different textures and experiment with color combinations. I feel a sense of freedom when I paint icons. But even when experimenting, I try to stay within the canon. In iconography, there are centuries-old rules of how content relates to color, and I follow it. But at the same time I am looking for a new sound that could emphasize the content of a particular work.

What makes an icon an icon? Put differently: what makes an icon different from a painting, even a painting of a religious subject?

Carlo Zvirynsky, one of the restorers of the Ukrainian icon of the late 20th century, encouraged new compositions and approaches to create icons to deepen spiritual experiences and facilitate prayer. He noted that the most important thing is that the icon comes closer to God. In sacred art, therefore, the very purpose, the foundations of Christianity and moral responsibility remain unchanged. The rest should be adapted to the requirements of the time, because tastes, artistic sense, styles, materials, technical solutions and everything else change. For Christians of the Eastern tradition, icons do not exist in ordinary times and in everyday space, as art does. Therefore, the icons do not have a real style, as the term is usually used, only canonicity.

It is believed that the Christian church has not developed any of its own artistic style and that it is open to all tastes, to all manners of presentation. The church, and consequently sacred art, have adapted to the changing styles and means of expression in art. Like any art form, sacred art develops and adapts to change.

However, the icon cannot be representative, as it is not a domestic or historical genre in art. Instead icons depict transformed persons and reproduces timeless events. The icons completely refute the mimetic way of addressing, which claims to correspond to the usual, everyday vision.

It is important to harmoniously combine the naturalism of the image and abstraction in the icon, which is the reason for the stylization in religious works of art. Any abstraction must reflect reality, not depart from it. Thus, the icon must contain figurative images. Along the same lines, icons are characterized by the reverse perspective, a change in the natural appearance (deformation) of things on the icons like the absence of gravity.

Also, the theology of the Eastern Church gives a majestic role to geometry, the conduction of human thought from the world of phenomena to the divine order. The interpretation of Euclidean forms in symbolic categories in the icon has a long tradition. For centuries, all of Christianity has paid homage to the idea that there is an analogy between geometric elements and what is divine. It did not agree with the theory of general chaos and the mechanistic image of the world.

It may seem banal, but still the canon makes the icon an icon. Despite innovations, the liturgical icon must remain within the canon. Also the person who paints any kind of religious painting – it doesn’t matter if it’s the icon or abstract piece – should be faithful and be aware of what they believe in.

For Western Christians unfamiliar or even suspicious of icons, what would you say to them about icons?

I noticed that recently there has been a trend of spread the iconography in western countries. More and more people are interested in Eastern iconography and I am pleased with this.

The main purpose of Byzantine iconography and contemporary iconography based on the Eastern tradition is to represent timeless events and transfigured persons, to show the idea of divine glory and light. The icon is timeless. That is, it is not tied to a specific time or historical context. From this it follows that the icon can’t be mimetic as it doesn’t display everyday life. This is why biblical figures and scenes can appear to look so strange. Rethinking the metaphorical meanings of religion by the human mind made it possible to create a stylization. This applies not only to Christian art, but also to the art of other religions, as well as the art of antiquity. On the one hand, the stylizationmeans simplification and accessibility. On the other hand, it makes a picture incomprehensible and complicates perception of the icon by a person accustomed to “realistic” art.

Aesthetics, which includes mastery of execution, observance of the laws of composition and anatomy, of course, must be characteristic of the icon. However, this does not apply to the physical beauty of the depicted persons. Hesychasts believe that physical attractiveness is undesirable and sinful, because any admiration for beauty can lead to temptation.

From what I know, there is rich tradition for how to depict various saints and scenes (i.e., you paint Jesus in a certain way, you paint Mary in a certain way). How do you understand your role as an iconographer? Where does the tradition fit in relation to innovation? Related to this, so much of contemporary art is about expression – expressing the artist’s self/experience/views of the world. How does iconography fit into this?

I must admit that I’m happy to take part in the revival and development of Byzantine iconography in particular Ukrainian iconography. Also I’m happy to be a representative of contemporary iconography.

It’s normal when artists express themsevles and their views in any kind of art. We all are humans with our imagination and ideas. We are created in the image of God so we are created to create. Every person is talented and it’s important not to bury the talent in the ground.

It is said that the icon is painted by God as the Bible is written by God with humans assistance but I don’t want to downplay our role. As a matter of fact, the human factor is fully present.

The modern iconographer rethinks many symbols and makes them available to contemporary audience.

A large group of artists, in particular my colleagues from LNAA approach the icon dynamically and innovatively, paying tribute to the contemporary ethos of the artist and the style of contemporary art. Between the two views – more conservative and innovative – everyone seems to tends to one or another pole.

The innovative approach to iconography can often be condemned, leading to the idea that artists, focusing too much on creativity and self-expression, forget about spirituality and prayer. It can be suggested that they pay more attention to visual effects than sacred content when they selfishly try to express their own “I” in Him and his saints, instead of glorifying the Creator. They are even sometimes accused of competing with each other in the originality of creative approaches and remoteness from tradition, and so on.

However, I don’t think this is really fair. Looking back at previous centuries, we can identify a large number of icon-painting schools. Looking back through history we see centers of masters, whose work differed in the manner of execution, stylistic features, reflection of aesthetic preferences in certain regions, and skill as well. Various traditions and versions of the icon of biblical scenes and saints have developed.

Ideally, well-trained painters, whose diligent work and constant prayer have opened them to the presence of the Holy Spirit, will create new interpretations of traditional themes. However, each of these fresh interpretations must immediately resonate with everything that happened before (and, later, with everything that will come). The Church confirms this resonance with a blessing.

I wonder if you could share some photos of some of your favorite icons you’ve created and tell us about them?

There are three icons I’d like to share. The first two are “I am the Light for the World” and “Their divinition spread throughout the Earth.” In these pieces I reflect on the idea of divine light.

White light is a combination of all the colours in the colour spectrum. The sum of all the colours produces white, which symbolizes divinity and purity in iconography. On the icon “I am the Light for the World,” Christ the Pantocrator is depicted in the middle of the round board. I painted the colours of the colour spectrum without significant changes. The light is divided into 12 colours directly on the background behind the Pantocrator. This displays the infinite space of the Universe and divine glory of our Lord. Jesus himself is dressed in white clothes as on many icons, especially the icon of Transfiguration.

The second icon is called “Their divinition spread throughout the Earth.” This is the icon of Pentecost. Every apostle wears clothes of a particular colour of the colour spectrum. The light of Christ is divided equally among them. They have become the light of Christ. In the center the dove which symbolizes the Holy Spirit is depicted in white. The apostles, as a part of the heavenly community, display the greatness of the Holy Spirit. Filled with the Spirit, they now convey the idea of the divine light. The square symbolizes the Earth where the light of faith shoud be spread on all four sides of the icon, every edge of the world.

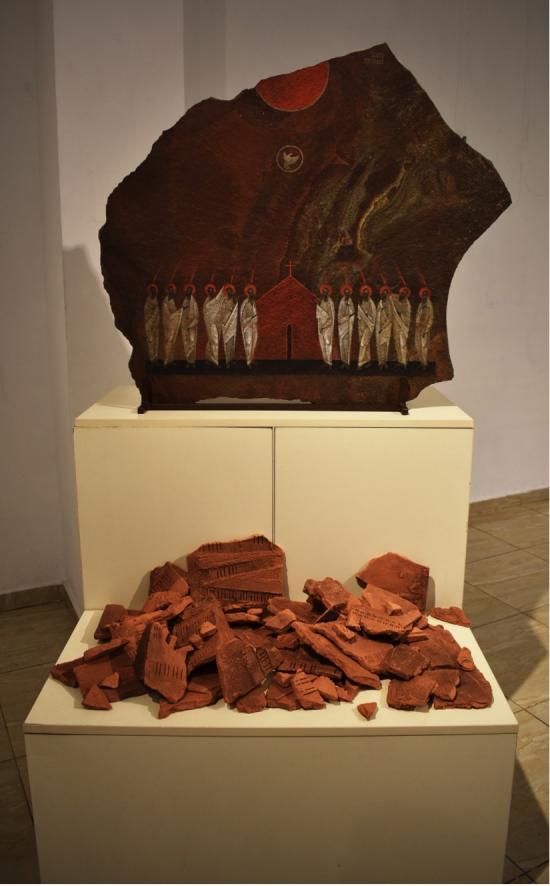

The third icon is called “Ecclesia.” The word “church” comes from the Greek ecclesia and means community or assembly. The composition “Ecclesia” includes the ceramic Tower of Babel (broken to pieces) and Pentecost behind it painted on the surface of stone.

The Tower of Babel is the antithesis of Pentecost. The Tower is an earthly structure, an ecclesia with earthly values that grasped after heaven. The Church founded on the day of Pentecost is the true heavenly Church. The iconographic composition “Ecclesia” contrasts the elements of the composition using figurative and technical means.

The icon of the Pentecost is depicted on the stone, as the stone symbolizes the church of Christ. The icon of the Descent of the Holy Spirit is somewhat different from the classic examples on this subject: the apostles are depicted standing, not sitting in a semicircle on the pulpit, there is no old man in a black cave, which symbolizes the world in darkness. The apostles are divided into two equal groups, between which is the space that fills the image of the Jerusalem chamber. It has the shape of a triangle – a symbol of the Holy Trinity, and is crowned with a cross – a symbolic Crucifix, which testifies to the presence of Christ.

The Tower of Babel is made of ceramics. At first I sculpted it out of clay, as described in the Book of Genesis, then smashed it. The prototypes of the Tower of Babel are the ziggurat temples, which were built of burnt clay. Clay symbolizes confusion and instability. So, here I represent this sense in the materials used. Burnt clay and stone are contrasted – one is short-lived, the other is eternal. One is created by human hands the other is created by God.

…

If you’d like to see more of her work or even purchase an icon, you can visit her website: http://khrystynakvyk.com