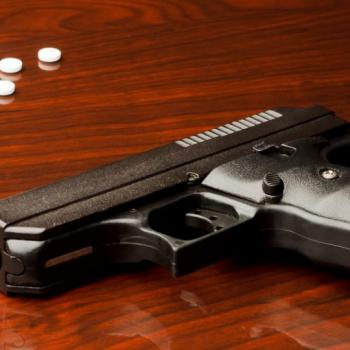

Faced with two of the most despised presidential nominees in modern American history, the temptation to play the electoral equivalent of Vizzini’s battle of wits from the movie “The Princess Bride” is nearly irresistible. It’s not about choosing the right cup, we’ve been told ad nauseum for months. It’s about not choosing the wrong cup.

But what if both cups are poisoned?

Since most voters have no more immunity to corrupt and debased politicians than they do to iocane powder, a minority is considering either sitting out this election or voting for a third party next week. But most are still resolved to choose between the poisoned cups. So in order to make the choice more palatable, many are redefining what it means to vote. Instead of supporting their party’s terrible candidate, they’re rationalizing their vote as a negation of the other candidate. They’re not voting for the lesser evil, you see. They’re voting against the greater evil. And you should, too!

But there are strong reasons to believe “voting against” candidates is neither logical nor responsible. Here are just four.

- It assumes one party has a right to your vote.

The idea of “voting against” someone assumes that you owe your vote to one or the other candidate, and that by withholding it, you’re depriving him of something to which he has a birthright. Otherwise, all of this talk about “helping elect the other candidate” is nonsense. If you vote for nether, you’re helping neither.

But this is a very peculiar theory of voting—one in which your consent falls into a column automatically, and not because a candidate has earned it or cleared a minimum threshold for leadership. Under this theory, a candidate must merely be less revolting and do less to warrant withdrawing your vote than his opponent.

There’s no real opt-out here. If you choose to vote third party or not at all, then you’ll be told you’re depriving one candidate of a vote you owe him. And not only that, but you’ll be told you’re effectively voting for the opponent, and every policy she supports!

Incredibly, this is true even if you’ve never had an R or a D on your voter’s registration. Merely holding a specific view (on abortion, for example) is enough to place you in someone’s column, no matter how you feel about the candidates, themselves. It’s a lot like union membership. Minding your own business and doing your job isn’t an option. You are expected to join up and pay your dues. If you don’t, then you’re effectively supporting the boss man, and you will have your arm twisted.

- It assumes the ends justify the means.

Many naively think that voting means supporting the candidate we want in office. Not in 2016. This year, we’re told, we should vote against the candidate who will do the country the most harm, even if that means voting for a candidate who offends our consciences, and who we believe it unfit for office.

But like all utilitarian calculations, this one assumes we’re omniscient. In reality, of course, we can’t know the future. And as some ethicists have already pointed out, a true utilitarian vote doesn’t just take into account what each candidate promises to do in office. It also takes into account the long-term damage an unscrupulous or compromised leader could do to the causes he represents while in office. As Alexander Hamilton wrote, “If we must have an enemy at the head of Government, let it be one whom we can oppose, and for whom we are not responsible, who will not involve our party in the disgrace of his foolish and bad measures.”

Ideally, we should steer clear of utilitarian calculations and ask instead which, if any candidate, our principles oblige us to support. But even granting this ends-justify-the-means philosophy, there’s a strong argument against electing politicians who will probably disgrace us and poison the public against our cause. If our only duty is to reduce harm, then throwing our support behind someone who may irreparably damage our own camp is counterproductive.

Ideally, we should steer clear of utilitarian calculations and ask instead which, if any candidate, our principles oblige us to support. But even granting this ends-justify-the-means philosophy, there’s a strong argument against electing politicians who will probably disgrace us and poison the public against our cause. If our only duty is to reduce harm, then throwing our support behind someone who may irreparably damage our own camp is counterproductive.

And those who insist that “this country won’t survive four years with the other candidate in office,” need to realize how familiar their words sound. I’m old enough to remember five prior “most important elections in the history of our country,” all of which folks said would “permanently alter the course of the nation.” 2016 may well be the most important election in American history. I don’t know. But citizens have said that about every election since George Washington left office. How much are we willing to stake on being right this time?

- It brings out the worst in the two-party system.

“Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” author, Douglas Adams, offers a prescient satire of this election in “So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish.” One of his characters asks why a world with a democratic form of government and fair elections is ruled by space lizards whom all the voters despise. “Why don’t the people get rid of the lizards?”

“It honestly doesn’t occur to them,” replies the other character. The people continue to vote for lizards because “if they didn’t…the wrong lizard might get in.”

Voting for the lesser of two evils just makes next election’s two evils greater. A commitment to always “vote against” the worse of two major candidates means we will vote for virtually anyone, as long as he or she is pitted against a suitably repulsive foil. There’s no floor. And if we continue rewarding bad candidates, accepting the social entropy that’s chipping away at our inhibitions, we will continue getting worse candidates. Not only that, but if a political party knows you will vote the line no matter what, then your vote is effectively useless.

In my conversations this season, some have seriously defended the idea that in an election between the two worst candidates imaginable—say, Hitler and Stalin—we would have a duty to vote against the greater evil. For many, there is no practical limit to this principle. There is no point at which we have a collective duty to say, “this is where I get off the train.”

- It’s moral evasion.

“Voting against” candidates tends to function as cover for supporting unfit or degenerate opponents. In reality, the “lesser of two evils” ceases to be lesser when it’s the evil we choose. And the trouble with surrendering our moral agency is how it tends to leave us willing to defend and excuse anything from “our guy.” After all, we are not complicit in helping a wicked leader come to power if we were only voting against a leader who was more wicked, still, right?

This game of make-believe gets much uglier when some of us decide not to play. A recent exchange on Fox News between conservative pundits Sean Hannity and Laura Ingraham, and former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee, became a three-way attack on holdouts who refuse to support the Republican nominee for president.

Ingraham accused these folks of “standing with” Hillary Clinton in defense of killing babies. “That’s what ‘Never Trump’ stands for, I guess,” she huffed. “Roe v. Wade and partial birth abortion. Fantastic.”

“All of these ‘Never Trumpers’ out there,” agreed Huckabee, “need to get off their keister, if you will, stand up and recognize—”

“Get off their ***!” interrupted Hannity. “Tell them to get off their *** and stop being a bunch of crybabies.”

Conservatives who have opted out of voting for a major party candidate have done so because they view both choices as unacceptable. Those urging us to “vote against” the greater evil, see this as aiding and abetting the enemy. Not only that, but refusing to vote is actively supporting all that the other side stands for and promises. If we don’t vote for a terrible candidate who claims to be pro-life, we’re told, we have baby’s blood on our hands.

But this leaves accusers in the uncomfortable position of arguing that they’re not responsible for the evils of their candidate, but that folks voting for neither are responsible for the evils of the other candidate. Picking a side, evidently, absolves us of moral culpability. But refusing to pick a side makes us responsible for whatever evil befalls the country.

This kind of moral pretzel-making is the clearest argument for rejecting the theory that it’s possible to “vote against” a candidate. Instead, we should recover a philosophy of voting as the means by which the governed give their consent and choose their leaders. What happens at the polling place should not be seen as a game of wits to keep the poisoned cup as far from us as possible. When they’re both poisoned, there is no right choice but to walk away.