Savvas Costi writes: Given our natural survival impulse, you might expect most people to welcome the prospect of being able to live forever.

However, this wasn’t the response of Jean-Luc in the latest instalment of the Star Trek franchise. By the end of series one of Star Trek: Picard, (spoiler alert!) he asks in alarm: “You haven’t made me immortal!?”.

This is one of a number of themes explored in the latest Big Conversation between Professor Nick Bostrom and another Picard, not a former Captain of the Enterprise, but a fellow specialist in the area of Artificial Intelligence – Professor Rosalind Picard.

Facing Our Mortality

The link with science fiction is a natural one given the pervasiveness of this topic within the entertainment film industry. But advances in technology seem to increasingly blur the boundary between sci-fi and sci-fact. Is technology really the key to immortality? And would we want it?

For many of us, the 2020 pandemic brought our mortality into focus as we faced a mounting death toll in the news, with some of us feeling the sting closer to home as we tragically lost loved ones. A famous English writer once said how “death tends to concentrate the mind wonderfully”. For those yet to give much consideration to the prospect of immortality, a reminder of life’s fragility has a way of raising the issue in a manner that demands attention.

While mourning the loss of his wife to cancer, C.S. Lewis noted how her absence felt “like the sky, spread over everything”. The resulting rupture leaves us wondering; where have they gone? What happens when I die? “Is everything sad going to come untrue?”.

Into The Unknown

Both Bostrom and Picard shared some reservations around the idea that life could go on indefinitely, much like our beloved Jean-Luc from Star Trek, but there was common ground in wanting something more, something ‘beyond’ our current lot.

In a fascinating piece in The New Yorker, we learn that Bostrom is a fee-paying member for Alcor, a cryonics facility in Arizona who would be responsible for effectively freezing his body after death, in the hope that technology will either one day revive him or upload his mind into a computer.

What is striking is that the technology seems to be developing quite rapidly, so much so that in the space of just seven years, between two gatherings of Artificial Intelligence (AI) experts, ethicists and legal scholars, questions that had once seemed fanciful were now becoming increasingly plausible. It’s “a new frontier” as Bostrom calls it, and this comes with a fresh sense of both optimism and trepidation as we sail into the unknown.

John Lennox has already raised the alarm that “the technology is developing far faster than the ethics to cope with it” (I reviewed his book about AI last year on Ian Paul’s blog). But can the transhumanist goal to extend our natural lifespan or revive those already deceased ever be achieved?

Immortality

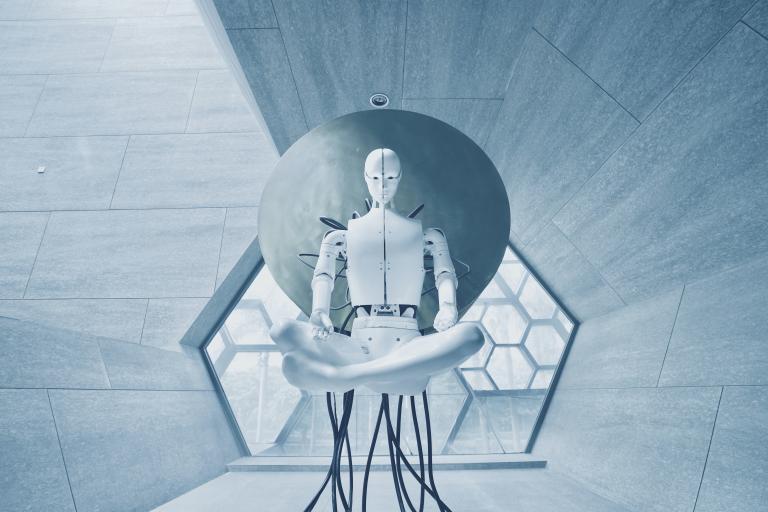

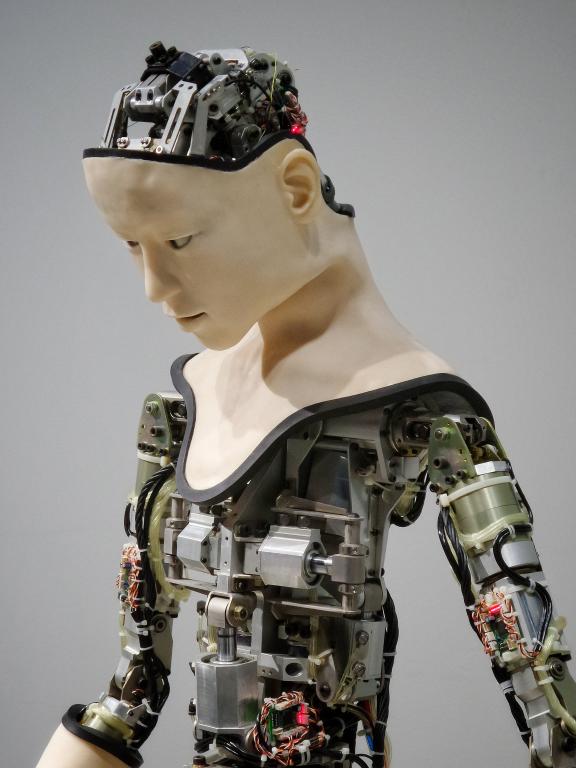

As explored in the conversation between Bostrom and Picard, the answer will depend on what we mean by immortality. Picard informs us that in the future it might be possible to construct something like a synthetic humanoid robot with intimate knowledge of all the data generated from our digital footprint. At the very least, this would be a way to resurrect all our online activity into a “digital form” that we could interact with amounting to “a kind of immortality”.

Given that the dictionary actually offers two definitions of immortality; one being ‘the ability to live forever,’ and the other being ‘the quality of…[being] remembered for a long time,’ it’s worth recognising that it would be this latter definition that would best fit with Picard’s description above. So, in one sense, immortality would have been achieved, but in another sense it wouldn’t, because the real person would still be deceased.

Consciousness

And then there is the question relating to consciousness; will it ever be possible to create conscious machines? For Bostrom, he believes that “a digital implementation was possible,” but Picard was more sceptical given that, “we don’t see a path towards building conscious experience”. There is also an important difference between ‘representing’ or ‘mapping’ consciousness, and the everyday feelings and experiences that we’re all familiar with.

Lennox reinforces the same point when he quotes Professor Joseph McRae Mellichamp:

“It seems to me that a lot of needless debate could be avoided if AI researchers would admit that there are fundamental differences between machine intelligence and human intelligence – differences that cannot be overcome by any amount of research…‘the artificial’ in artificial intelligence is real.”

If we’re not able to construct consciousness ourselves, then the prospects are low for resurrecting those who have lived before. Those holding on to the hope that we will one day do this must acknowledge that they are placing a lot of faith in AI research. Picard helpfully distinguishes how this would be a speculative faith, rather than one grounded in evidence.

If you read Sharon Dirckx’s work, you’ll see that part of the issue resides in the assumption that physical matter alone can explain everything. “If we are dealing with a closed system of meaningless matter and non-conscious neurons, how did these come to generate conscious minds?” With naturalism, the appearance of life on earth remains a mystery. But if we’re far more than matter, then perhaps our consciousness points to the existence of a non-material source. Might this be the Mind of God?

An hour into the conversation, Picard sounds very similar to C. S. Lewis when she talks about us being wired for immortality. Many of us will share a desire to exceed the average lifespan of around 80 years (if we’re fortunate). Timothy Keller has also written about how love instinctively desires permanence, which partly explains why losing loved ones to either the aging process or death is so painful.

What best explains this universal longing to live forever? It might just be the survival instinct kicking in again, or perhaps the words of Ecclesiastes 3:11 ring true:

“He has made everything beautiful in its time. He has also set eternity in the human heart.”

Hints Of Transcendence

For the skeptic, all of this by itself is unlikely to mount a convincing case for God’s existence, but at the very least we can see how this is consistent with a Christian worldview. If Christ has risen from the dead, then Christians are hopeful of their own future upgrade, clothed with the imperishable and made to dwell with God.

This also fits nicely with Charles Taylor’s assessment that we all now inhabit a “cross-pressured space”, living with the tension of being in a secular age that is haunted by hints of transcendence. The “nevermore” that is the finality of death written about in Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven, leaves us unsettled and ignites a longing for something beyond the merely physical. The good news is that if Christ’s resurrection really is a historical event in the past, then death no longer has the final word. Everything sad will come untrue.

Given all we learned about generating massive amounts of online data for ourselves, I was surprised that a discussion around the issue of surveillance wasn’t explicitly explored, although it was hinted at. Picard did mention how the biggest threat to humanity would not be AI itself, but rather that the technology would fall into the wrong hands and be used as a means for exploitation and control.

C.S. Lewis was on point again when he said:

“Man’s power over Nature is only the power of some men over other men with Nature as the instrument.”

We should all be alarmed by what has been happening in China, where sadly the technology has likely been used as a means for preserving the power of an elite few.

Are We Living In An AI Simulation?

There was also the question of how do we know what is real? Might we be living in a simulation much like The Matrix that has been constructed by a Superintelligence? I and many other philosophy teachers have explored this with students in lessons on epistemology. How can we be certain that our thoughts bear any relation to reality at all?

The answer is that we can’t, and the Matrix conundrum highlights how reason itself is a matter of faith. That doesn’t mean we should all now throw ourselves under a bus because of a newly discovered existential crisis. Bostrom is right to say that we should “start by assuming that everything is as it appears to be”.

Andrew Wilson struggled with the same problem until he came across The Oxford Companion to Philosophy which says:

“Do you know that you are looking at a…book [or a screen] right now rather than, say, having your brain intricately stimulated by a mad scientist?…the conclusion that you really are looking at a book…explains the aggregate of your experiences better than the mad scientist hypothesis or any other competing view.”

All of my experiences so far suggest that it is more likely that this is the real world. The burden of proof lies with those claiming it to be a simulation to provide compelling evidence to support that claim.

Big Conversations

Overall, it was a fascinating conversation between Bostrom and Picard on a topic that is going to become increasingly more pressing. Had there been more time, it would have been great to hear Picard elaborate on what she said half an hour into the conversation about the implications of having a consciousness that is both “fully known,” and “algorithmically specified”.

I also wonder if more could have been said around the dangers of an excessive reliance on technology that diminishes our humanity, as Sherry Turkle has argued.

Nevertheless, it was an informative discussion that typifies much of what I have come to love about The Big Conversations series; having a civil and honest discussion with someone who thinks differently to you is becoming a rarity in today’s polarised world.

As Trevin Wax has helpfully written: “The goal…[is] to think, and thinking requires finding people who challenge you in ways that grow your reasoning skills.’

Bostrom and Picard gave us exactly that.

Savvas Costi is a graduate from the London School of Theology who currently leads the Religion and Philosophy department at a secondary school in East Sussex. He did his teacher training at King’s College London. He is married with one daughter.

Click here to watch Professor Rosalind Picard and Professor Nick Bostrom discuss this topic further on The Big Conversation.

Subscribe to the Unbelievable? podcast

Join NT Wright, Tom Holland, Josh McDowell and others online at the Unbelievable? conference on 15th May