Thanksgiving is upon us. This year, I find myself reflecting upon God’s generosity in Christ for which I am most thankful. I wish to take this opportunity to reflect upon how God’s generosity in Christ shapes the Christian life.

A theology of God’s gracious love fosters an ethic of gratitude. I preached on Philemon this past Sunday at Ascension Presbyterian Church and believe this passage in Scripture reveals this orientation. Now some may see in Paul’s letter to Philemon a subtle form of manipulation whereby Philemon is forced to free his slave Onesimus. I beg to differ. I believe Paul truly appeals to him in love as a result of God’s grace at work in Paul’s, Philemon’s and Onesimus’s lives in relation to one another and the whole church (koinonia).

Ever the master of rhetoric, Paul appeals to Philemon: he is thankful for Philemon refreshing the hearts of the saints (vs. 7) and is expectant that Philemon will refresh Paul’s heart by freeing his runaway slave Onesimus (vs. 20), who has not only become Paul’s son by saving faith while in prison in Rome (vs. 10) but has also become Paul’s heart (vs. 12; the same root word for “heart” is used in each instance: splachna—vss. 7, 12, 20). As Robert Jewitt has written, “Philemon…has Paul’s heart in his hands.” (Paul the Apostle to America: Cultural Trends and Pauline Scholarship {Westminster/John Knox Press, 1994}, p. 66).

Having “derived much joy and comfort” from how Philemon has refreshed the hearts of the saints, Paul could demand that Philemon provide more of the same. However, Paul resists this urge. Paul writes in Philemon 8-10: “Accordingly, though I am bold enough in Christ to command you to do what is required, 9 yet for love’s sake I prefer to appeal to you—I, Paul, an old man and now a prisoner also for Christ Jesus— 10 I appeal to you for my child, Onesimus, whose father I became in my imprisonment.” Here we see that Paul does not compel Philemon, but rather appeals to him in the Lord.

Given Paul’s and Philemon’s partnership, Paul requests that Philemon receive Onesimus as he would receive Paul (vs. 17). To receive him as an equal would entail receiving him as a free man. The idea that tends to float about in Evangelical circles that internal transformation does not involve a transformation of social status is seriously mistaken (it is as mistaken as the idea that the transformation in our spirits that leads to a transformation of social status arises from our own capacities and proclivities*). Paul appeals to Philemon to welcome Onesimus back on equal terms in the Lord and in the flesh. Onesimus is to be welcomed back like he would Paul, his partner in the faith (vs. 17). This follows from what Paul wrote one verse earlier: “no longer as a bondservant but more than a bondservant, as a beloved brother—especially to me, but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord” (vs. 16).

No doubt, it will cost Philemon something to free his slave. He is not alone. Paul is willing to bear with him the debt incurred by Onesimus’s situation (vss. 17-19a). Paul offers to pay because he has derived great benefit from Onesimus’s presence, since he has freely cared for Paul while he is in prison (vss. 11-16), even as Paul has cared for Onesimus (vs. 10) and Philemon (vs. 19b). In this relational context, Paul is confident that Philemon will obey from the heart and will do even more than Paul requests (vs. 21). They are all in one another’s debt in the Lord who is at work in and through them.

This reminds me of a statement that Dr. John M. Perkins once made. He said, “I have a debt of gratitude to pay to the Lord” based on God’s loving grace at work in his life. I, too, have a debt of gratitude to pay in view of God’s loving grace at work in my own life, just as Paul and Philemon and Onesimus did. This same Onesimus who had been useless, once saved, becomes useful; no doubt, like Paul the “Apostle of the heart set free,”** he too is freed from the heart and now serves willingly, freely out of a spirit of gratitude. Just as Onesimus serves Paul freely, Paul asks Philemon to give Onesimus his freedom. The give and take of mutual benefit that is communion (koinonia) stems from gratitude which flows from God’s loving grace at work in their lives in relation to one another.

When God’s gracious love takes over, gratitude kicks in and gets one going. An ethic of gratitude that flows from God’s gracious love is not cheap, but very costly. As Dietrich Bonhoeffer writes, “Cheap grace is the grace we bestow on ourselves. Cheap grace is the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, communion without confession…. Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate.” (Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Cost of Discipleship, {Touchstone, 1995}, p. 44).

Cheap grace is also grace without one another. Such isolated grace fails to account for koinonia, which was mentioned at the outset of this post. Koinonia is present in Philemon. In verses 6 and 17, we find references to this theme of koinonia. Koinonia entails communion, sharing, partnership, and partner. Koinonia flies in the face of cheap grace, which does not involve others. Cheap grace is all about “God and me” in isolation, which does not even include God, but simply isolated individuals who turn God’s grace into a distorted projection—which “we bestow on ourselves” (Cost of Discipleship, p. 44). Costly grace, on the other hand, involves us caring for one another from the heart and in the flesh. Manumission (liberation from slavery) flows from our Christ-centered mission to bring forth equality: spiritual transformation involves social transformation, which requires and leads to greater forms of solidarity of mutual benefit and sharing, that is, costly communion (koinonia).

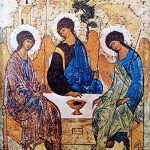

How can it be otherwise since such koinonia—such costly communion—flows from God’s communal life of Father, Son and Spirit in eternal fellowship? God’s costly grace flows forth from the throne of holy love as the Father sends his Son into the world through the Spirit to bring freedom through his embrace of the world on the cross. This gracious triune love alone fosters an ethic of gratitude.

This piece is cross-posted at The Institute for the Theology of Culture: New Wine, New Wineskins and at The Christian Post.

_________

*Here I wish to affirm and embrace Donald Bloesch’s depiction of what is referred to as “Evangelical Contextualism”: “Evangelicals in this tradition speak more of graces than of virtues. Virtues indicate the unfolding of human potentialities, whereas graces are manifestations of the work of the Holy Spirit within us. It is not the fulfillment of human powers but the transformation of the human heart that is the emphasis in an authentically evangelical ethics.” Donald G. Bloesch, Freedom for Obedience: Evangelical Ethics in Contemporary Times (San Francisco: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1987), p. 191.

**F. F. Bruce refers to Paul as such in the title of his book on Paul’s life (Paul: Apostle of the Heart Set Free (Eerdmans, 2000).