Pimping involves the objectification and abuse of human bodies for profit. Pimping is an atrocious way for one person to treat another.

Similar themes are found in the Bible. The Old Testament sometimes refers to God’s people as a prostitute (take Hosea for example). Their wayward hearts lusted after things other than God and they played the prostitute. God was their scorned lover who remained faithful and did not abuse or pimp them; their other lovers abused them, though (See Ezekiel 16, 23).

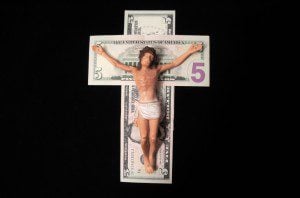

If we are not careful today, we will try pimping Jesus in a religious sense, even though we can never control him. Jesus always remains Lord. In a similar vein, we may treat the Bible as a talisman or good luck charm or means of advancing careers in and through religion rather than obey God no matter the cost; such self-advancement will cost us prophetic rebuke and credibility where it matters most—with God.

Søren Kierkegaard addresses this matter with hyperbolic rage in “The Attack Upon ‘Christendom.’” There he challenges the polarity between genuine Christianity and bourgeois religion or Christendom and its negative impact on the Christian faith’s truth claims:

Here then is the proof and the disproof at the same time! The proof of the truth of Christianity from the fact that one has ventured everything for it, is disproved, or rendered suspect, by the fact that the priest who advances this proof does exactly the opposite. By seeing the glorious ones, the witnesses to the truth, venture everything for Christianity, one is led to the conclusion: Christianity must be truth. By considering the priest one is led to the conclusion: Christianity is hardly the truth, but profit is the truth.

No, the proof that something is truth from the willingness to suffer for it can only be advanced by one who himself is willing to suffer for it. The priest’s proof—proving the truth of Christianity by the fact that he takes money for it, profits by, lives off of, being steadily promoted, with a family, lives off of the fact that others have suffered—is a self-contradiction; Christianity regarded, it is fraud.[1]

It is quite easy to succumb to the temptation to profit from Christianity. The temptation is quite subtle. Just think of the Temple, Sabbath, and Torah. They were important religious realities in Jesus’ day. Many people honored God by honoring them. However, people dishonored God by honoring only the Temple, Sabbath, and Torah. They did not see that Jesus is the living Temple (John 2:13-22), the living Sabbath Rest (John 5:1-18), and the living Torah (John 5:19-47), standing in the people’s midst. And even if they did see him, those in power who controlled religion for personal and political purposes could not cope with Jesus’ claims and presence. According to the canonical gospels, they used the sacred building, book and day of the week as control mechanisms, yet missed the living Lord who had given them those things. But they could never control Jesus, even though they stoned, scourged, and crucified him. He kept rising.

This is not simply a historical problem. As noted at the outset of this piece, it is a problem that we find alive and well today. Like Ricky Bobby of Talladega Nights, who prays to the eight pound, six ounce baby Jesus, we pray to the Jesus of our own imagination, trying to use him to make a profit in various ways. But he does not fall prey to our whims and wishes. As with Aslan in C. S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia, he’s not tame, but he’s good.

What are some of the control mechanisms with which we struggle? What do they conjecture (falsely) about God? How do we let go of our control mechanisms and understand and experience God for who God is?

[1]Søren Kierkegaard. “The Attack Upon ‘Christendom,’” in A Kierkegaard Anthology, ed. Robert Bretali (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), pp. 464–465. See Bretali’s editorial comments that introduce Kierkegaard’s essay; according to Bretali, Kierkegaard will later claim that he exaggerated his critique to challenge the status quo for the sake of “restoring the general balance.” (p. 435).