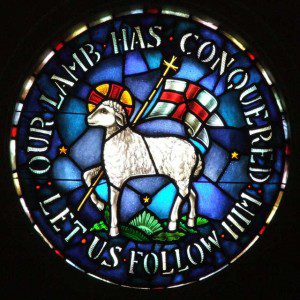

I like bunnies, but I prefer lions and lambs at Easter. After all, the Bible does not make use of rabbits in reference to the resurrected Christ, but rather lions and lambs, as in the Lion of the Tribe of Judah and Lamb of God. Revelation 5:5-7 reads,

“Weep no more; behold, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has conquered, so that he can open the scroll and its seven seals.” And between the throne and the four living creatures and among the elders I saw a Lamb standing, as though it had been slain, with seven horns and with seven eyes, which are the seven spirits of God sent out into all the earth. And he went and took the scroll from the right hand of him who was seated on the throne. (ESV)

What is the context of this statement? John of the Apocalypse has a vision of God’s throne room (Revelation 4 and 5). He weeps because no one has been found worthy (Revelation 5:4) to take the scroll from the hand of the Almighty and open it so as to unleash God’s judgments on the earth. Without the opening of the scroll and breaking of its seals, there will be no redemption for God’s suffering church at the hand of Emperor Domitian. One of the elders comforts John by exhorting him to gaze upon the Lion of the Tribe of Judah who alone is found worthy to open the scroll and its seven seals. The lion, who is a slain lamb raised to new life, takes the scroll from the hand of the Ancient of Days to enact God’s redemptive judgments and deliver God’s suffering people from the hand of their oppressor.

“You are worthy” (“Worthy are you,” ESV) and “our Lord and God” greeted Emperor Domitian when he appeared in triumphal procession. The Apocalypse commandeers such language and applies it to the Ancient of Days and to the Lion who is the Lamb slain and raised bodily to new life. In effect, John seeks to convey to his readers that Caesar loses; Christ wins.[1]

The Book of Revelation is a very political book, and is by no means intended to convey an otherworldly spirituality of how to escape suffering. Rather, John exhorts his readers to overcome through suffering so as to sit with Jesus on his throne, just as the resurrected Jesus has overcome and sits with his Father on his throne (See Revelation 3:21-22).

It is little wonder that Domitian would want to stamp out Christianity. He understood how dangerous the celebration of Easter’s resurrected Jesus was to his dominion involving Caesar worship. Faithful Christians would not bow the knee to him due to their belief in Jesus, the resurrected One who alone is worthy of divine honor.[2] No matter how hard Domitian tried, he could not stamp out the Christian faith from his empire—to the chagrin of the Nietzsche’s of this world old and new.

I can only wonder how Christians who had copies of John’s Apocalypse were treated. Perhaps not unlike those found to possess copies of John Steinbeck’s Allied propaganda The Moon Is Down in fascist controlled countries during World War II.[3] The fundamental difference between the two works is the Apocalypse’s focus on Jesus as the resurrected and conquering Christ who alone brings freedom, especially for those suffering oppression and persecution. Even so, Karl Barth made a connection between Jesus’ resurrection and the war against Hitler and National Socialism. Jesus’ resurrection served as the basis for making war on the Third Reich—a counterfeit millennial kingdom.[4] After all, Jesus alone is Lord, not the Fūhrer, as the Barmen Declaration written earlier by Barth conveys.[5] It is worth noting that the Swiss authorities had Barth’s essay “A Letter to Great Britain” banned.[6]

The celebration of Jesus’ resurrection from the dead cost the early church greatly. After all, it is quite dangerous. The belief in Jesus’ bodily resurrection on Easter Sunday also costs the church greatly in other parts of the world today, as for example, our Coptic Christian brothers and sisters under ISIS control. Jesus alone is Lord.

How dangerous is the celebration of Easter to you and me? How much does it cost those of us who live in the West in relative comfort? As our children go about searching for chocolate Easter eggs and bunnies in the house and yard, how do we account for our faith that leads others to hunt down Christians in other parts of the world, not bunnies?

Do our consumer comforts get in the way of affirming Jesus as Lord of all—even Lord over our comforts? Do we realize that God comforts the afflicted and afflicts the comfortable, as the old saying goes, and not as another saying goes, that he awards us with our best lives now? Come Easter, may we seek to identify with our brothers and sisters who are paying with their lives for their celebration of Jesus as the resurrected Lord. May we pray for them. May we grieve with them. May we rejoice with them. May their own suffering encourage us to identify all the more with Jesus—the Lion and the Lamb—who is Lord of all. After all, our shared hope in Jesus’ cruciform and resurrected life is his people’s blessed comfort at Easter throughout the ages.

__________________________

[1]See the following treatments of this theme: Robert H. Mounce, The Book of Revelation, The New International Commentary on the New Testament, revised (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 1998), pages 126-127. Hanns Lilje, The Last Book of the Bible, trans. Olive Wyon (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1957), pages 108, 109; Ethelbert Stauffer, Christ and the Caesars (London: SCM Press, 1955), pages 150-159; and Robert E. Coleman, Singing with the Angels (Grand Rapids: Fleming H. Revell, 1980), pages 40-41.

[2]See Stauffer, Christ and the Caesars, pages 163-164.

[3]According to the back cover of the Penguin Twentieth Century Classics edition of Steinbeck’s The Moon Is Down, “in Fascist Italy, mere possession of a copy of the book was punishable by death.” See John Steinbeck, The Moon Is Down, with an introduction by Donald V. Coers (New York: Penguin Books, 1995).

[4]See Karl Barth’s essay, “A Letter to Great Britain from Switzerland,” in This Christian Cause (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1941).

[5]Refer here to the “Theological Declaration of Barmen”: http://www.sacred-texts.com/chr/barmen.htm.

[6]The reason for the ban by the Swiss authorities was that Barth, in keeping with “his earlier writings,” employed “his theological framework to support a position hostile to a foreign state, holding up a mirror to the Confederation in a way which is likely to disturb correct relations between Switzerland and this other state.” Karl Barth, letter to Dr. Bally-Gerber, 6 August 1941; quoted in Eberhard Busch, Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts (London: SCM Press, Ltd., 1976), page 310. Barth had earlier lost his professorship in Germany in 1935 based on his refusal to swear an oath to Hitler (to whom he had personally mailed a copy of the 1934 Barmen Declaration, for which he had served as the principal author).