The doctrine of the Trinity is not just for Trinity Sunday (June 11th, 2017), but for every day of the year. Unfortunately, according to Lesslie Newbigin, many Christians from the High Middle Ages up until the latter half of the twentieth century were averse to referencing the Trinity, perhaps not even on Trinity Sunday:

The doctrine of the Trinity is not just for Trinity Sunday (June 11th, 2017), but for every day of the year. Unfortunately, according to Lesslie Newbigin, many Christians from the High Middle Ages up until the latter half of the twentieth century were averse to referencing the Trinity, perhaps not even on Trinity Sunday:

It has been said that the question of the Trinity is the one theological question that has been really settled. It would, I think, be nearer to the truth to say that the Nicene formula has been so devoutly hallowed that it is effectively put out of circulation. It has been treated like the talent that was buried for safekeeping rather than risked in the commerce of discussion. The church continues to repeat the trinitarian formula but—unless I am greatly mistaken—the ordinary Christian in the Western world who hears or reads the word ‘God’ does not immediately and inevitably think of the Triune Being—Father, Son, and Spirit. He thinks of a supreme monad. Not many preachers, I suspect, look forward eagerly to Trinity Sunday. The working concept of God for most ordinary Christians is—if one may venture a bold guess—shaped more by the combination of Greek philosophy and Islamic theology that was powerfully injected in the thought of Christendom at the beginning of the High Middle Ages than by the thought of the fathers of the first four centuries.[1]

Why the aversion? Perhaps it was due to a growing and pervasive rationalism. Newbigin was not alone in lamenting the lack of Trinitarian thought forms in Western thought. Michael Buckley has also noted the lack of engagement of Trinitarian theology in Christian apologists’ engagement of budding atheists in the modern period.[2] While rationalism is an ongoing problem, other forces that wage war today against robust Trinitarian reflection in many circles are consumerism and pragmatism. We easily settle for quick-fix, base commodity spirituality and short-term solutions to problems. However, quick fix spirituality and pragmatism cannot help us contend against impersonalism and materialism. The increasingly impersonal and materialistic view of the world in the modern age beckons us to give account once again to the Father’s interaction with the cosmos—not imposing his will from without—but entering into the world through his Son and Spirit’s interpersonal and communal engagement from within the historical process.

While the Trinity is not just for Trinity Sunday, but for every Sunday and every day of the year, it is not the case that any construal of “the Trinity” goes. Newbigin took issue with certain social Trinitarian constructs being developed in his day (for example, in Konrad Raiser’s ecumenical thought) in such a way that they dominated Christological categories and the gospel message in service to democratic notions of governance. Newbigin challenges this approach: “What gives ground for anxiety here is the positing of a Trinitarian model against the model of Christocentric universalism. The doctrine of the Trinity was not developed in response to the human need for participatory democracy! It was developed in order to account for the facts that constitute the substance of the gospel.”[3]

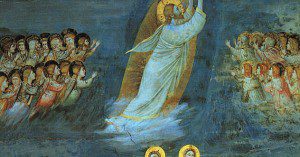

While needing to safeguard against excessive or abusive uses of the Trinity for our own ends, we should not throw out the baby with the dirty bathwater. One of the most striking features and implications of Trinitarian reflection for the gospel is that we are not alone. Thus, it would be short-sighted or narrow-minded to limit the Trinity’s significance to Trinity Sunday. Jesus goes with us, even as he invites us to go into all the world, as reported in Matthew 28:18-20. The Great Commission is the Great Communion in which we participate in the life of the triune God while bearing witness to the good news of God calling all humanity to respond to his personal love through faith in Jesus every day of the year across the globe. In Matthew 28:18-20, we find that we are called to baptize people into the name of the Father, Son, and Spirit, teaching Jesus’ disciples to obey his commandments which are summed up in loving God with all our hearts and our neighbors as ourselves (Matthew 22:34-40). As Jesus goes with us, and the Spirit dwells in us and empowers us, we invite people to enter God’s community as members of the divine family.

Hierarchal, impersonal and materialistic constructs of reality that would seek to eclipse the triune God, on the one hand, and democratic notions seemingly imposed on the triune God, on the other hand, will never displace the reality that God in Jesus through the Spirit dwells in our midst as Immanuel “the whole of every day” until “the very end of the age”[4] (Matthew 1:23; Matthew 28:20). Only in this relational and mysterious manner can the church truly overcome the impersonal and secular mundane. The Trinity is not just for Trinity Sunday, but for all of us the whole of every day throughout the year and age.

_______________

[1]Lesslie Newbigin, The Open Secret: An Introduction to the Theology of Mission, rev. ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995), pages 27–28.

[2]Michael J. Buckley, S.J., At the Origins of Modern Atheism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), page 33.

[3]See the full context of the quotation (page 7) in Lesslie Newbigin, “The Trinity as Public Truth,” in Kevin J. Vanhoozer, ed., The Trinity in a Pluralistic Age: Theological Essays on Culture and Religion (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 1997), pages 7-8. Never should relationality overshadow God as divine Trinity. Rather, the reverse should always remain the case. Paul Molnar critiques a social-Trinitarian state of affairs in which “Relationality [has become] the subject, and God the predicate.” Paul D. Molnar, Divine Freedom and the Doctrine of the Immanent Trinity: In Dialogue with Karl Barth and Contemporary Theology (London: T. & T. Clark, 2002), page 227.

[4]D. A. Carson asserts that Matthew ends with “promise” rather than “commission” (See Matthew 28:20). “Our English ‘always’ masks a Greek expression found only here, and meaning ‘the whole of every day.’ Jesus promises to be with His disciples, as they make disciples of others, not only on the long haul, ‘but the whole of every day,’ ‘to the very end of the age.’” D. A. Carson, God with Us: Themes from Matthew (Eugene: Wipf & Stock, 1995), page 163. Further to this point, I maintain that even and especially in his ascended state, Jesus is present to us through the Spirit in the most intimate way.