Whether we are conservative or liberal or somewhere in between, we struggle to account for Jesus. If we are conservative, we might not have difficulty calling him literally God, but we might have difficulty with his claim that it’s harder for the rich to inherit heaven than for a camel to pass through the eye of the needle (Matthew 19:16-30). If we are liberal, we might not have trouble with Jesus’ claim that the sheep are those who care for the poor, the imprisoned and the homeless, but we may have difficulty with Jesus’ claim that he pronounces judgment, welcoming some to heaven and sending others to hell as the divine judge (Matthew 25:31-46). In one way or another, it is easy to treat Jesus, his actions and his teachings as interesting and suggestive, but still dismiss them as fake news whether explicitly or implicitly. To hold dearly to his personal claims as well as claims on our personal lives is rather too hard and costly.

Both sides of the conservative-liberal spectrum come to a head in Jesus’ conversation with the rich young ruler in Matthew 19:16-22. Coming to Jesus to ask him what he must do to be saved, Jesus tells the rich young ruler to sell his possessions and give the proceeds to the poor to have treasure in heaven, and then come follow him. Only God can make such demands! Can you think of any man or woman who in their right mind could tell someone else that they needed to surrender everything and follow him or her to be saved? That would be absurd, even scandalous.

Speaking of scandalous, whether or not you think Gotthold Lessing was simply trying to dismiss the New Testament account of Jesus as Lord and God and his call on our lives, Lessing was addressing what is often called the ‘scandal of particularity’. As Lessing puts it, “The accidental truths of history can never become the proof of necessary truths of reason.” Again, Lessing writes:

We all believe that an Alexander lived who in a short time conquered almost all Asia. But who, on the basis of this belief, would risk anything of great permanent worth, the loss of which would be irreparable? Who, in consequence of this belief, would forswear forever all knowledge that conflicted with this belief? Certainly not I. But it might still be possible that the story was founded on a mere poem of Choerilus just as the ten year siege of Troy depends on no better authority than Homer’s poetry.

And still again, Jesus’ miraculous life “is the ugly, broad ditch which I cannot get across, however often and however earnestly I have tried to make the leap.”[1] In Lessing’s estimation, historical events can never bridge the gap to universal truth.

Lessing was not alone in his evaluation of historical particulars. He was surrounded, so to speak, by a great cloud of witnesses from the East and West. For many in the ancient West and East, the only way to get across the divide to universal truth is through reason (Greek philosophy) or mystical experience (Indian/Hindu), as Lesslie Newbigin observes.[2] In addition to Newbigin, who rejects Lessing’s move, another noteworthy historical example of someone claiming to make that leap through historical events is Søren Kierkegaard. Or, to put it more accurately, Kierkegaard believes Jesus bridges that gap as the eternal Logos who is enfleshed (See John 1:1-3, 14, 18).

In his critical assessment of the Greek rationalist tradition hailing from Socrates and Plato and extending to Hegel, Kierkegaard argues that we must look beyond ourselves for truth, for within ourselves we will only discover “untruth,” “for the learner is indeed untruth.” In contrast to Socrates as the midwife who serves as an occasion for the awakening of truth or really untruth within ourselves, and not truth itself, Kierkegaard refers to the teacher who is not simply a teacher, but who is “the god himself.” This teacher reveals truth and provides the basis for understanding, transforming the student in the process. The teacher—Jesus—is for Kierkegaard “savior,” “deliverer,” “reconciler,” “judge.”[3]

Kierkegaard does not leave off dealing simply with Jesus’ claims about himself, but elsewhere talks about his radical claims on our lives. While Kierkegaard would later acknowledge that he used hyperbole in order to restore balance,[4] nonetheless his remarks challenge all of us ‘priestly types’ regardless of our theological orientation:

Here then is the proof and the disproof at the same time! The proof of the truth of Christianity from the fact that one has ventured everything for it, is disproved, or rendered suspect, by the fact that the priest who advances this proof does exactly the opposite. By seeing the glorious ones, the witnesses to the truth, venture everything for Christianity, one is led to the conclusion: Christianity must be truth. By considering the priest one is led to the conclusion: Christianity is hardly the truth, but profit is the truth.

No, the proof that something is truth from the willingness to suffer for it can only be advanced by one who himself is willing to suffer for it. The priest’s proof—proving the truth of Christianity by the fact that he takes money for it, profits by, lives off of, being steadily promoted, with a family, lives off of the fact that others have suffered—is a self-contradiction; Christianity regarded, it is fraud.[5].[5]

To apply Kierkegaard’s hyperbolic exhortation, one must view ministry not as a means for comfort and glory, but as a profound call to service, even to the point of glorious suffering for Jesus and others.

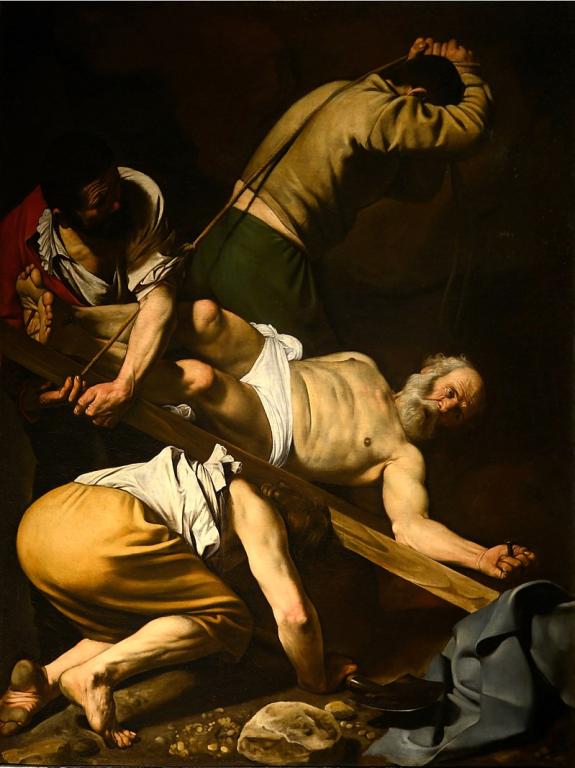

Let’s be honest. In a Moralistic Therapeutic Deistic world where God exists to safeguard our happiness, Kierkegaard’s two-sided challenge can prove quite unsettling to each of us. After all, who wants to be told they are “untruth,” “frauds,” “fake news”? At least, the apostolic community responsible for supposedly conjuring up the scandalous biblical account of Jesus as Lord and God who calls on us to lay down our lives for him really did lay it down for Jesus. Unlike those cult leaders today who claim that if you want to make a million bucks, start your own religion, Peter and Paul’s religion required that they lose their lives for Jesus. They practiced what they preached. There was nothing fake about that. Perhaps all our direct and indirect discounting of Jesus and his claims, as recorded by his followers, is simply a smokescreen so we do not have to follow in their footsteps.

_______________

[1]Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, “On the Proof of the Spirit and of Power,” in Lessing’s Theological Writings, (Stanford University Press, 1957), pages 51-55.

[2]Lesslie Newbigin, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), page 2.

[3]Søren Kierkegaard, Philosophical Fragments, edited and translated by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985), pages 11, 14, 15, 17-18.

[4]See the editorial notations introducing Kierkegaard’s essay. Robert Bretali points out that Kierkegaard later acknowledged he exaggerated this critique for the purpose of “restoring the general balance” rather than reside in the status quo. Søren Kierkegaard, The Attack Upon “Christendom,” in A Kierkegaard Anthology, edited by Robert Bretali (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), page 435.

[5]Kierkegaard, The Attack Upon “Christendom,” pages 464–465.