Conspiracies are always secretive. As such, it is hard for me to fathom the doctrine of the incarnation as a conspiracy. Against the backdrop of Platonic thought, the creedal teaching of the incarnation was known far and wide as heretical by the mainstream ideological standards of the day. Certainly, there were fertility cult myths about the gods becoming human. But the idea that God became this human, and this human alone, flew in the face of the pantheon of the Greek and Roman gods and the Pagan religious establishment, not to mention the Jewish hierarchy. The early church was not trying to hide its ‘heresy’: it wore it on its sleeve and paraded it in public.

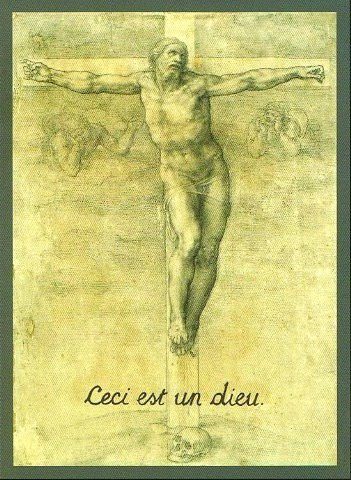

How so? John’s Gospel makes no apologies, nor does it hide its claims in cryptic speech: Jesus is the Good, or the Logos (Word) of the Platonic Good. Jesus is God. How heretical, according to the reigning Platonic and neo-Platonic systems of thought! The idea that the Good, or the divine Logos, became human, was preposterous (It was and is also quite invasive. It would be much better for our personal space and comfort level if God stayed out of our neighborhood, business and family affairs, unless we call on him to help resolve some matter before departing again, not unlike a moralistic therapeutic deity). According to Platonic thought, the Good is eternal, not temporal, constant, not changing, one, not many or plural. And yet, John writes straightaway, “And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14; ESV; italics added).

Yesterday’s heresies are today’s orthodoxies. So, too, today’s orthodoxies are fast becoming tomorrow’s heresies. While many people will not take shots at Jesus, but the church, still even Jesus being viewed as God is suspect in many quarters in our post-Christian or post-Christendom society. Today’s Christian community is not alone. Its first century Christian counterparts were well aware of the heretical nature of their beliefs against the dominant cultural Zeitgeist. They did not seek to hide their ‘heretical’ teaching of Jesus being God, though. Nor should we seek to hide it. After all, the teaching that Jesus is God in the flesh was never a conspiracy, just a ‘heresy’.

People can say all they want about the early church trying to suppress alternative gospel accounts and keeping them out of the canon. But the religious elites of the day were trying very hard to suppress the church’s own gospel accounts. The teaching that Jesus has not come in the flesh (which 1st John 2:18-27 and 1st John 4:1-6 challenge) was the majority report within Paganism back in the day, though not that of the church.[1] The New Testament canon with its teaching that Jesus was God Almighty in the flesh was the minority report, and the church suffered greatly for its official teaching. As Robert Jenson puts it in his Systematic Theology, the general presupposition in the ancient period was that the gap between “pure timeless deity and sheer temporality” could only be filled by intermediaries who “as images of deity, are neither quite timeless nor merely temporal,” and most certainly not God, if they can come into contact with the material, temporal world.[2] Unlike Dan Brown’s good old conspiracy theory, the apostles were not best-selling authors who made big at the box office, too. If only they had tried to keep their short stories secret, they might not have been so ridiculed or might not have died so soon.

But something or someone kept the disciples from going clandestine—the resurrection of Jesus from the dead. According to the biblical accounts, the apostolic community went into hiding immediately following Jesus’ trial and death. Only after his resurrection did they come out into the open and the light of day. The apostolic community went about in public proclaiming Jesus as the resurrected Lord who conquered the grave. For them, the good news was that divine goodness was not solitary but relational and communal. Divine goodness was not locked up in heaven or a tomb either, but became flesh and then immortal, bringing eternal life to us here and now in space and time.

Rather than view the world as evil and beyond hope, the incarnation is the greatest news ever told, not sold. Though Jesus was rich, he became poor to give us the gift of eternal life. Though he knew no sin, he became sin so we could become God’s righteousness. He became what we are so that we could become what he is. Far from being a conspiracy that covers up ugly lies, this tale is just too good to be true. Perhaps that is why so many won’t believe it: we’d rather settle for fanciful fiction, or even a filthy lie.

_______________

[1]Bart Ehrman writes about the subject of the church’s take on Jesus’ identity as divine and human in the context of analyizing The Da Vinci Code: “Once again, there are elements of both fact and fiction in Teabing’s view. Constantine did call the Council of Nicea, and one of the issues involved Jesus’ divinity. But this was not a council that met to decide whether or not Jesus was divine, as Teabing indicates. Qu[i]te the contrary: everyone at the Council-and in fact, just about every Christian everywhere-already agreed that Jesus was divine, the Son of God. The question being debated was how to understand Jesus’ divinity in light of the circumstance that he was also human. Moreover, how could both Jesus and God be God if there is only one God? Those were the issues that were addressed at Nicea, not whether or not Jesus was divine. And there certainly was no vote to determine Jesus’ divinity: this was already a matter of common knowledge among Christians, and had been from the early years of the religion.” Bart D. Ehrman, Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), pages 14-15. For another source giving in depth and cogent argumentation regarding the early reception of Christ’s divinity, see: Larry Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity (Grand Rapids: Eerdman’s Publishing, 2005). Rather than focusing on Christological titles as many do (Martin Hengel, for example) to demonstrate early conceptions of divinity, Hurtado is particularly important because he focuses on early devotional practices. His conclusion is that early Christian worship and veneration clearly demonstrates Jesus was seen as the God of Israel in human form. In addition, as one of the most noted Patristic scholars of late, Lewis Ayres, writes in his book Nicaea and Its Legacy: “despite the claims of some mythmakers who point to Constantine as the major party responsible for doctrinal decisions at the council, Constantine was not even concerned with doctrine at the outset of his call to convene a council. Rather, “it initially took the efforts of bishops like Ossius and Alexander of Alexandria to persuade him that anything significant was at issue …” Lewis Ayres, Nicaea and Its Legacy: An Approach to Fourth Century Trinitarianism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), pages 87-88. And, as another noted Patristics scholar writes, far from being an invention of Nicaea, “the church of the fourth century inherited a tradition of Trinitarian discourse that was pervasively embedded in its worship and proclamation, even if it was lacking in conceptual definition.” Khaled Anatolios, Retrieving Nicaea: The Development and Meaning of Trinitarian Doctrine (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2011), page 15. Moreover, as both Ayres and Anatolios claim in their respective books, the idea of Nicaea as a council having monolithic authority and causation upon the beliefs of the church is mistaken. After Nicaea, doctrinal disputes continued not just regarding Arianism, but also about the very meaning of the Nicene Creed itself. It was only due to the tireless argumentation of the oft-exiled Athanasius and several others like the Cappadocian Fathers that a particular interpretation of the meaning of the Nicene creed itself was retroactively seen as authoritative by the end of the 4th century.

[2]Robert Jenson, Systematic Theology: Volume 1 – The Triune God (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), pages 53-54. I am grateful to my colleague Derrick Peterson for his contributions to this post pertaining to the Patristic period.